Why don't you just sell all your stocks and buy ETFs, you'll probably have better performance?

Why people pick stocks

On October 4th, 2019, Joaquin Phoenix’s rendition of the infamous Batman villain, Joker, premiered in a psychological thriller that bears the same name. The film harks back to an early Joker, then named Arthur Fleck. As the film progresses, Fleck’s behaviour becomes increasingly absurd. A deterioration in the protagonist's mental state sees his acts of violence become more extreme and frequent as he loses touch with reality.

In the final scene of the film, Fleck is unrecognisable as he is interviewed by a psychiatrist. Without stimulus, he begins to laugh hysterically in his iconically disturbing fashion as he smokes a cigarette in the interrogation room. When the psychiatrist asks him “What’s so funny?” he explains he was thinking about a joke. “You wanna tell it to me?”, she asks. To which the Joker replies “You wouldn’t get it”. Frank Sinatra’s That’s Life begins to play and the film ends.

The scene has since been adopted by the meme community, including myself. This particular meme is humorous because, like all good humour, there is a strong undercurrent of truth pulsing through the punchline. In my case, I question why individuals bother buying individual stocks, where the odds of beating the market are stacked against them, instead of buying the market and living a relatively carefree life. My rendition is partially self-deprecating and alludes to the little white lie we all tell ourselves as individual investors; that we are different, and despite the majority who will inevitably fail, we will beat the market.

To a layman, an investor’s dedication to beating the market over their lifetime appears absurd. The trade-off, time spent doing other things, is huge. We each have a finite amount of time on this earth. To spend countless hours which I assume add up to years of one’s life, only to underperform the market, may appear wasteful. Insanity is repeating the same thing hoping for different results. Consider the aggregate of individual investors trying to beat the market. Most will fail. Thus, on the aggregate level, these people look crazy. But there are some who manage this feat, and for them, the time was “worth it”. The Joker is batshit crazy. Most of us know that we are likely wasting our time trying to triumph over an index, yet we still do it anyway. Hence, we are all batshit crazy too. It takes a level of arrogance to beat the market, but sometimes arrogance is good. That little white lie we all tell ourselves is, in my opinion, a necessary falsity that instils belief. To do it, you must believe you can do it.

There are plenty of nuances we could unpack here but my point is this. Every good investor understands that what they are aiming for is hard to achieve, yet they do it anyway. For some, the monetary reward and alpha is all they care about. Others appreciate that the benefits of investing span far beyond an arbitrary total return quota. Everyone invests for their own reasons, so what drives people to buy stocks instead of just buying ETFs and going to the beach?

Stacked Odds

There is no denying the appeal of the stock market. It promises untold riches for everyday Joes that happens to stumble across the next Monster Beverage; which would have returned $4 million from a $1,000 investment in 1996; easier said than done. Like the lottery, which is predominantly played by the poorest in society, the stock market offers a golden ladder to escape poverty, struggle, or even just normalcy.

For someone who has the temperament of a lottery fanatic, ETFs are likely the best way to compound wealth over time. Yet, the same is true even for relatively sophisticated investors. Therein lies the irony. The upside is that individual investors with solid analytical abilities, critical thinking, behavioural advantages, and a dash of luck, do have the capacity to compound wealth considerably over their lifetime. Nevertheless, the odds are not in their favour.

You are unlikely to have an informational or analytical advantage: Bill Miller has frequently said the competitive advantages an investor can have are threefold; informational, analytical, and behavioural. For the average individual investor, it’s unlikely they have any of the three. In reality, the most attainable advantage is behavioural and this is an advantage that has to be carefully maintained and developed over a lifetime. It can take a lifetime to build emotional discipline, and a second to lose it, or something like that. My hunch is that every individual thinks they have the patience and pragmatism of a monk, but few actually do.

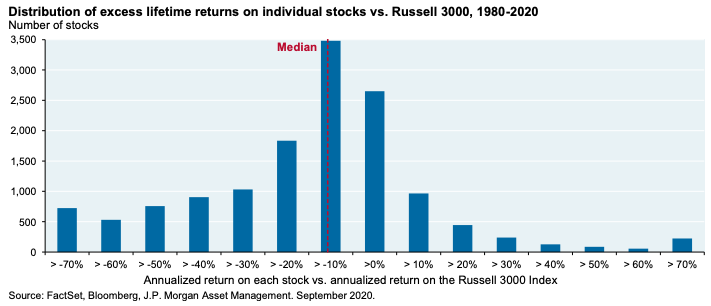

It’s unlikely you will pick extreme outliers like Monster Beverage, Chipotle, Amazon, or Apple and hold them long enough: Everyone loves a good multi-bagger story. While they may not be works of fiction, the influence of luck and survivorship bias are often exempt from these tales. There is near-insurmountable evidence that proves how difficult this can be. A 20211 study from JP Morgan shows that between 1980 to 2020 the median stock in the Russell 3000 underperformed the index while the winners generated the vast majority of excess returns. Remember this next time you think it's easy to find the "next Amazon".

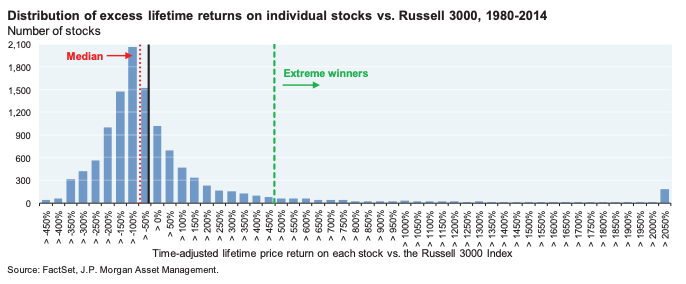

Below is an older version of this study2, from the years 1980 to 2014, which shows lifetime returns instead of annualised.

Most single stocks underperform Treasury Bills: It’s undeniable that “stocks” outperform lower-risk investments like government bonds most of the time, for most countries. This has been well documented. However, this refers to the aggregate universe of “stocks"; which in reality are led by the excess returns of a handful of outliers. Remove those handful of stocks, and you will reveal another story. This is the basis of Hendrik Bessembinder’s 2017 paper3; “Do Stocks Outperform Treasury Bills?”. His conclusion was startling.

He remarks that while the overall stock market outperforms Treasury bills, most individual common stocks do not, and “Of the nearly 26,000 common stocks that have appeared on CRSP since 1926, less than half generated a positive holding period return, and only 42% have a holding period return higher than the one-month Treasury bill over the same time interval”. He continues to argue that the positive performance of the overall stock market is attributable to the large returns generated by relatively few stocks. The following statistic is mind-blowing.

“When stated in terms of lifetime dollar wealth creation, one third of one percent of common stocks account for half of the overall stock market gains, and less than four percent of 28 common stocks account for all of the stock market gains. The other ninety six percent of stocks collectively matched Treasury-Bill returns over their lifetimes”.

He later updated the study in 20194, with similarly chilling results. This appears to be as good an advertisement for owning the market as any. There is evidence that finding one or two of these stocks in your lifetime can pay for most of your losers, and then some. But the tricky part is holding onto them for so long.

Why Do We Do It?

George Goodman, who went by the pseudonym Adam Smith, was the author of Supermoney. In the book, Goodman asks a friend why he buys individual stocks rather than buying funds despite the fact he continues to lose money. "If I couldn't look my stocks up in the paper, I'd really miss it," he replied. "Part of my life that I enjoy would be gone”. Some of you may read this and think “how tragic”, but that’s the reality many investors face today. For many, investing gives them a sense of purpose; a truly powerful force that when lost makes us feel empty. I can relate to that, so I want to begin with why I am drawn to investing, and then conclude with what you all think.

For me, I have been fascinated by business (and the many arms under the umbrella) since I was a teenager. This later developed into a passion for studying businesses, the micro and macro elements of decision-making, and human behaviour. I feel that the stock market is one of the meatiest hunting grounds for the real-time study of human behaviour and biases. There are lessons to be learned that are interoperable with real life, and it goes both ways. I also enjoy having an outlet for study; I feel strongly that continuous learning keeps the mind sharp. I can’t deny investing gives me a sense of purpose too; something to keep me engaged with the world around me. Whatsmore, I enjoy all of this and want to build wealth over time. I feel I have the temperament to ignore noise, but so does everyone else. Personally, I don’t really care if I beat the S&P 500 in the near term or medium term. This is part of the reason why a little over a third of my wealth is parked in funds. And lastly, I enjoy the social element of it. Since developing a network of investors online, I have made many friends, and this has led to opportunities that have been fun, weird, life-changing, and educational.

Why Do YOU Do It?

I asked you all what your reasons are, and have curated some of them below; adding commentary and merging repeated answers when appropriate. The first two are a great example of how different everyone’s realities are.

I sleep better owning ETFs because I don’t need to be worried about individual companies.

I sleep better owning individual stocks because I know what I own.

The irony of one investor losing sleep over individual stocks and the other losing sleep over the impossibility of understanding every company within an ETF is amusing. As one person responded; “Indexes are full of junk”. But both perspectives can co-exist, and both have merit.

I do it for the love of the game (which was a common response), not for the money. I like going to the beach, but it gets boring after a while, and I want a challenge. Investing, for me, is one of the most fun challenges there is. I'd venture to say that you have to have a genuine interest to succeed at it.

I believe in my ability to identify stocks that will outperform the market.

This was one of the most common responses; the little white lie.

Because it’s more about the process than the outcome. If your goal is to beat the market but you hate the process then you're in it for the wrong reasons. As long as you don't blow up your life savings, enjoy the process.

It's a small part of my savings. I know I have little to no skill in picking stocks, but I learn a lot and it's fun.

For me, it’s a way to learn. I guess being invested in a stock gives an incentive to learn (company, industry, markets, valuation), similar to tuition.

I’d hate to deprive myself of the opportunity to discover my countless flaws and biases.

While humorous, this one is so true. You learn a lot about your own behaviour, and the behaviour of others, by witnessing reactions to certain events and circumstances.

ETFs and other index proxies do not facilitate the price-discovery process (as specific stocks become more expensive, index-like investments buy more).

I love analyzing industries and businesses. But, I realized I could do that in an account worth about 10% of my investment portfolio and index the rest and know that I will still have way more than enough and not face single stock risk.

It’s more interesting to learn about companies & special sits than about ETF-based asset allocation. Buying single stocks and getting them right proves that you are smart and if you are like me, that is literally addictive.

I am smart enough to know I can’t beat the market but there are still companies I want to own shares in.

I just want to figure out 1% of what Buffett has figured out, which should be enough to set me up for life. The intellectual pursuit is more fun than the stock returns itself.

I love the challenge. Investing is like playing the best board game/video game. I've also beaten the market for many years and believe I can continue to do so. If I ever hit a point where I underperform for 5 years in a row, I'll probably seriously consider at least partially indexing.

Stocks are more interesting, with a higher probability of returns.

I'm happy to pay for things that I find deeply meaningful long term.

Underrated response. You can take it at face value, but I feel this one has layers.

The only good answer is you have an edge.

Because I’m a masochist apparently.

We do many things that we are not great at. We still do them anyway because it's fun.

I want more money.

After listening to everyone’s responses, I believe for most it boils down to intellectual pursuit, love of challenge, competitiveness, passion for learning or business, monetary gain, or an expectation that they can outperform. I believe one of the most underappreciated reasons is meaning. Whether we like to admit it or not, investing gives our life some kind of purpose; something to keep our minds switched on. Particularly as we age, it’s important to keep learning and prevent those areas of our brain from fading away.

Thanks for reading,

Conor

Honourable Mentions

Here is some other great stuff worthy of your time.

Babe, wake up, new Mauboussin paper just dropped; this one centred on the stages in the company life cycle.

Great story from Jamie Catherwood about the “tech” bubble of the 1690s that was catalysed by treasure hunts. Literally, vessels funded by the stock market to go explore the seas for treasure.

For those who enjoy reading great research and professionally curated charts and themes, I recently discovered Lykieon’s recurring charts of the month segment. They provide great splashes of colour on business, finance, and the macro environment.

An interesting piece about how the world’s largest ETF, SPY, will one day cease to exist thanks to a quirk in the legal structure used to America’s first and largest ETF Trust. More than $400 billion in AUM rests in the hands of 11 ordinary millennials born between 1990 and 1993.

Do Stocks Outperform Treasury Bills? (2017), Hendrik Bessembinder (here). H/T to Mosaic Asset for sharing this paper with me.

Just keep dollar cost averaging in, especially when things look the bleakest! ETF's are fantastic for the core part of your portfolio. Having single name positions for a small portion of portfolios also works well.

How many times have any of us read any article about any topic and its admixture is immediately clear; either...

01. The journalist is a terrible writer and does not know his or her topic;

02. The journalist is a terrible writer but knows his or her topic exceedingly well;

03. The journalist is an excellent writer but does not know his or her topic; or

04. The journalist is an excellent writer who also knows his or her topic exceedingly well.

You can count on the fingers of one hand the cohort that falls into group 4. The record is especially abysmal when the topic is specialized, often with its own jargon, such as finance.

You, Conor, begin to carve out a niche for yourself in group #4. I know not your professional aspirations - heck, I do not even know you! - but if your ambition includes a plenitude of time to do deep research and then write long-form narrative-style journalism, you have the the makings of a fine career ahead of you.

Godspeed.

David