The Fate of the SPY and $400b+ Rests in the Hands of 11 Ordinary Individuals

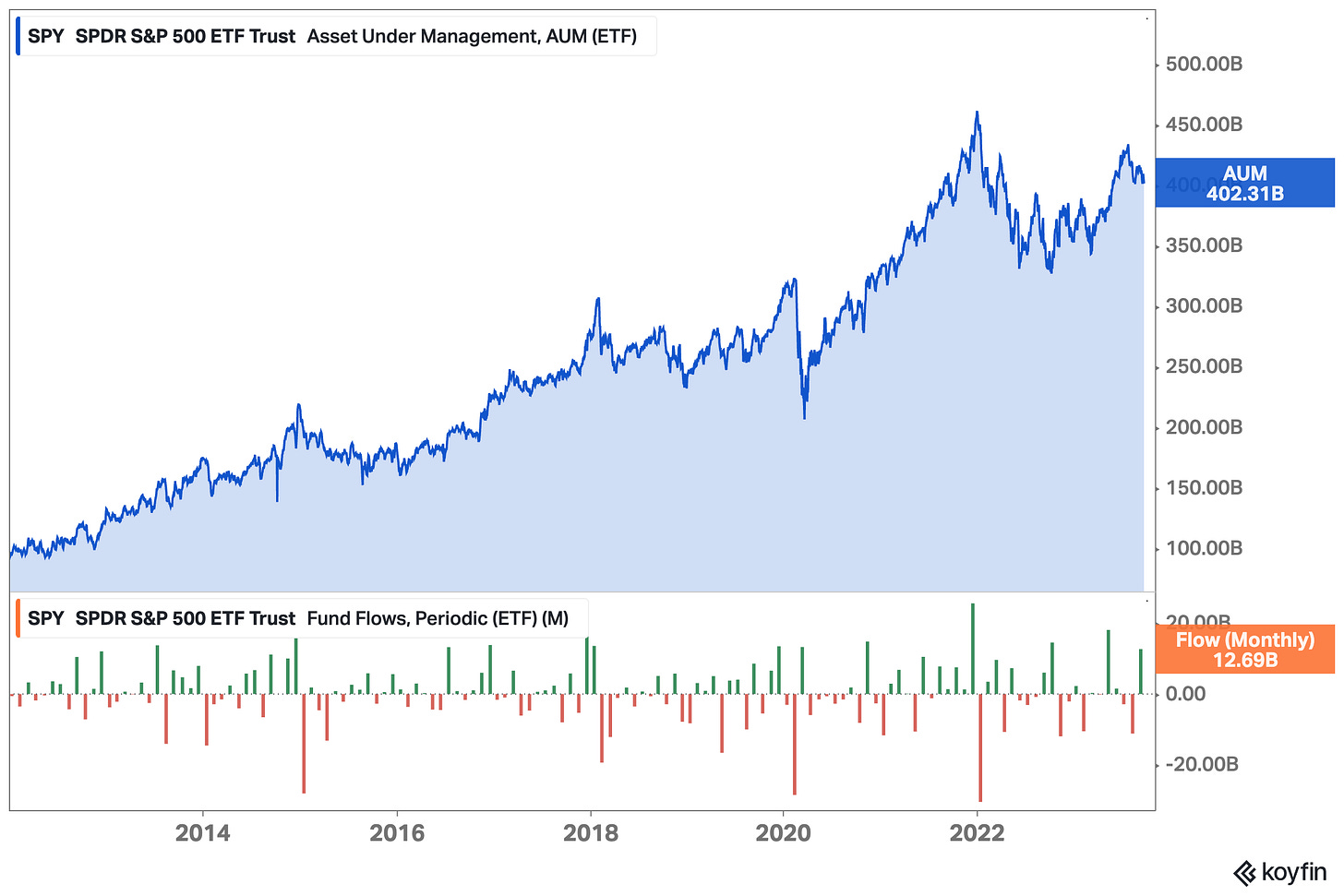

Thanks to a quirk in the legal structure used to set up America's first ETF

Before we begin; no, this isn’t some sensationalist bear porn doomer post about how the S&P 500 is nearing collapse. It’s a short tale of how one weird quirk in the legal structure used to set up America’s largest exchange-traded fund (ETF), the SPDR S&P 500 ETF Trust known as “SPY”, means the fund’s fate lies in the hands of eleven ordinary people. Launched in January 1993, SPY was the first ETF listed in the United States and has since become the world’s largest; amassing a gargantuan $400 billion in assets under management.

Okay, technically SPY wasn’t the first ever. Thanks to a slower regulatory approval process in the States, there was one ETF that pipped it to the post three years earlier; Canada’s TIPS fund. Nonetheless, SPDR’s S&P 500 fund was the catalyst for an explosion in ETF creation and adoption. Much in the same way that Helen of Troy was said to be the “face that launched a thousand ships” because of her ability to drive men to war, the SPY was the fund that launched a thousand funds.

Early Beginnings

In 1993, exchange-traded funds were a novel concept. By constructing the SPY fund, the issuer could create fund units that resembled a company’s shares. Institutions now had a way of providing passive, liquid, indexed funds to individual investors, at a low cost. Unlike mutual funds, ETFs could be traded intraday, they had no minimum purchase requirement, they were more tax efficient, and the annual fees were considerably lower than most comparable mutual funds. Sounds great, right?

Well, it took some time for the investment community to warm up to the idea; particularly asset managers. Initially “there was tremendous resistance to change” cites Bob Tull, then developer of new products for Morgan Stanley and an integral figure in the development of ETFs. The money that brokers generated from mutual funds was still more appealing and there was thought to be little money in shilling ETFs to clients.

“There was a small asset management fee, but the Street hated it because there was no annual shareholder servicing fee. The only thing they could charge was a commission. There was also no minimum amount, so they could have got a $5,000 ticket or a $50 ticket”.

Bob Tull

Despite the resistance from asset managers, ETFs were a tsunami that would eventually come crashing down on the industry; there was no stopping it. The awareness of index investing as a superior method of compounding wealth for the ordinary individual was an idea that was already catching steam; thanks in part to John Bogle, the founder of Vanguard. In 1976, Bogle launched the first index fund and would dedicate the rest of his life to preaching the sanctity of buying the market and going to the beach. The wheels were in motion, and ETFs gave regular people the ability to index more easily and cost-effectively. It was the individual investor’s appetite for ETFs that got the product off the ground in the early days. But it wasn’t an overnight success.

After launching the first ETF in 1993, the industry only had ~$2.5 billion in AUM by 1996, with 19 funds in circulation. By the turn of the century, there were only 80 funds, but with $65 billion in AUM, adoption was ramping. Just one year prior, in 1999, the Nasdaq 100 tracker ETF, QQQ, was born. Looking back on the security’s 20th anniversary in 2019 Dan Draper, then Managing Director of Invesco ETFs, recounted:

“When QQQ was launched in 1999, most investors were just learning about index-tracking investment products, and the transparency offered by an ETF was novel. It is interesting to look back 20 years later at how relevant and well-regarded the Invesco QQQ remains, even as much of the ETF landscape has changed”.

Eventually, ETFs would evolve from offering equity exposure, and branch out into other asset classes and themes. 1998 saw the creation of the first sectoral ETF. Factor-based ETFs came to market in the year 2000, the same year Europe began to offer ETFs. In 2002, the first fixed-income ETF was unveiled. For the first time, regular investors could easily gain exposure to bonds. Alternative weighting methodologies became available in 2003. In 2004, the first commodity ETF was born; the SPDR Gold Trust. In 2006, the first levered ETF made its way to the market.

By 2008, actively managed ETFs were issued and today, there is an ETF for just about everything. The trajectory of the assets allocated to ETFs grew significantly over the coming decades.

The SPY 11 Kids

Okay, but you came here for a story, I haven’t forgotten. Let’s go back to the late 1980s for a moment, before all of this explosive innovation took place. The exchange-traded fund was not something that existed. It was an idea inside some executive from the American Stock Exchange’s head. These executives rattled their brains; trying to figure out how they could take this idea and transform it into an investment vehicle that could list on the stock exchange. The structure for the fund they eventually landed on was a unit investment trust. However, up until then, unit investment trusts theoretically lasted for ~25 years and required a set termination date at inception.

To circumnavigate this short lifecycle, the guys at the American Stock Exchange amended the terms of the fund by using eleven individuals’ lifespans as the underlying determination of the fund’s termination date. The trust thereby dictated that the fund would terminate 20 years after these eleven individuals, born between the years 1990 and 1993, were all sleeping with the fishes, or by the year 2118, whichever came first.

From the fund’s official prospectus:

“The Trust has a specified lifetime term. The Trust is scheduled to terminate on the first to occur of (a) January 22, 2118 or (b) the date 20 years after the death of the last survivor of eleven persons named in the Trust Agreement, the oldest of whom was born in 1990 and the youngest of whom was born in 1993. Upon termination, the Trust may be liquidated and pro rata Units of the assets of the Trust, net of certain fees and expenses, distributed to holders of Units”.

There was no special process for selecting the eleven trustees; they were chosen because of their relation to individuals at the Exchange. Claire McGrath was the mother of one of the children and an aunt to two more; a former options division lawyer at American Express. She recalled a call going out for babies’ names that could be used by the trust and recounted:

“I had my son, and they asked if I would mind if they used him. It’s interesting because it’s an arcane rule that trusts always have to deal with, but it’s not a big deal. At the time, when we were creating these things, we had no idea they would become as spectacular”.

The children stood to gain no financial incentive from their roles, and many of them would not know about their status until they were adults.

So, What Happens?

In theory, the SPY will cease to exist upon the conclusion of either two of these events and be wound up like a regular trust. In 2019, Bloomberg reached out to State Street, the owners of the fund, and the New York Stock Exchange, which acquired the American Stock Exchange in 2008, for comment. The two institutions declined to comment.

The reality is that (a) this won’t impact anyone reading this in our lifetimes and (b) by the time the end eventually draws near, the likelihood is that there will be some form of transition process set in motion several years, or decades, in advance. It could be that a second version of SPY is created and assets are gradually migrated over time. Another thought… A little over one hundred years ago we invented the first airplane. Only a few decades ago, the internet became a sensation. Just yesterday I saw Lex Fridman do a podcast interview with Mark Zuckerberg using photorealistic avatars and mixed reality to mimic spacial connectivity; despite the duo being hundreds of miles apart. Lord knows what the world is going to look like another hundred years from now. ETFs might no no longer be prevalent, and this whole thing ends up being a moot point.

As Matt Levin later described in a Bloomberg column, “there is something magical about a lot of modern high finance. And if you know anything about magic, you know that it requires certain inputs. Occult inputs”. This seemingly benign call for babies’ names to be included in the legal documents for something as mundane as a fund termination clause, a fund structure that had no precedence and appeared to be experimental at best, is one of those magical moments. Who could have guessed the SPY would become the world’s largest fund? This story may contain no practical application or lessons to derive from it. But it is yet another arcane piece of historical stock market trivia that may or may not make you a more entertaining dinner guest.

Thanks for reading,

Conor

Honourable Mentions

Here is some other great stuff worthy of your time.

Sophie over at Inevitability Research breaks down how the world’s biggest luxury players, Ferrari, LVMH, and Hermes, compound heritage.

Cedric Chin from Commoncog discusses the capital cycle; “a simple idea with a bunch of fairly profound implications”. Really great stuff.

Todd Wenning from Flyover Stocks on the 15 questions to ask management teams. Even if you are not in the position to ask management teams questions, it’s a useful guide for understanding the difference between quality and poor questions in earnings calls & interviews.

Another banger from Morgan Housel, this time discussing the art of the written word and how writing for yourself can lead to the best outcomes.

Nice one!

Peculiar! Never heard about this topic before