Here is the Problem with Thematic ETFs

And how not to construct a Luxury ETF

Exchange-traded funds (ETFs) come in all shapes and sizes. The traditional low-cost, broad-index ETF would be vanilla-flavoured if it were an ice cream. So-called “smart beta” ETFs employ rules-based systems, conceived to outperform traditional market-cap-weighted index funds. Industry and sectoral ETFs are like the little cousins of the broad-index ETF; still pretty vanilla but more niche in their selection. Equities, corporate bonds, government bonds, derivatives, commodities, macro data series, passive, active… There is an ETF for everything. In plain English, an ETF is set up to achieve a goal and that goal is typically exposure to a basket of securities that relate to a specific market, characteristic, strategy, asset class, or theme. In return for the construction of this ETF, issuers and/or managers are paid a small fee.

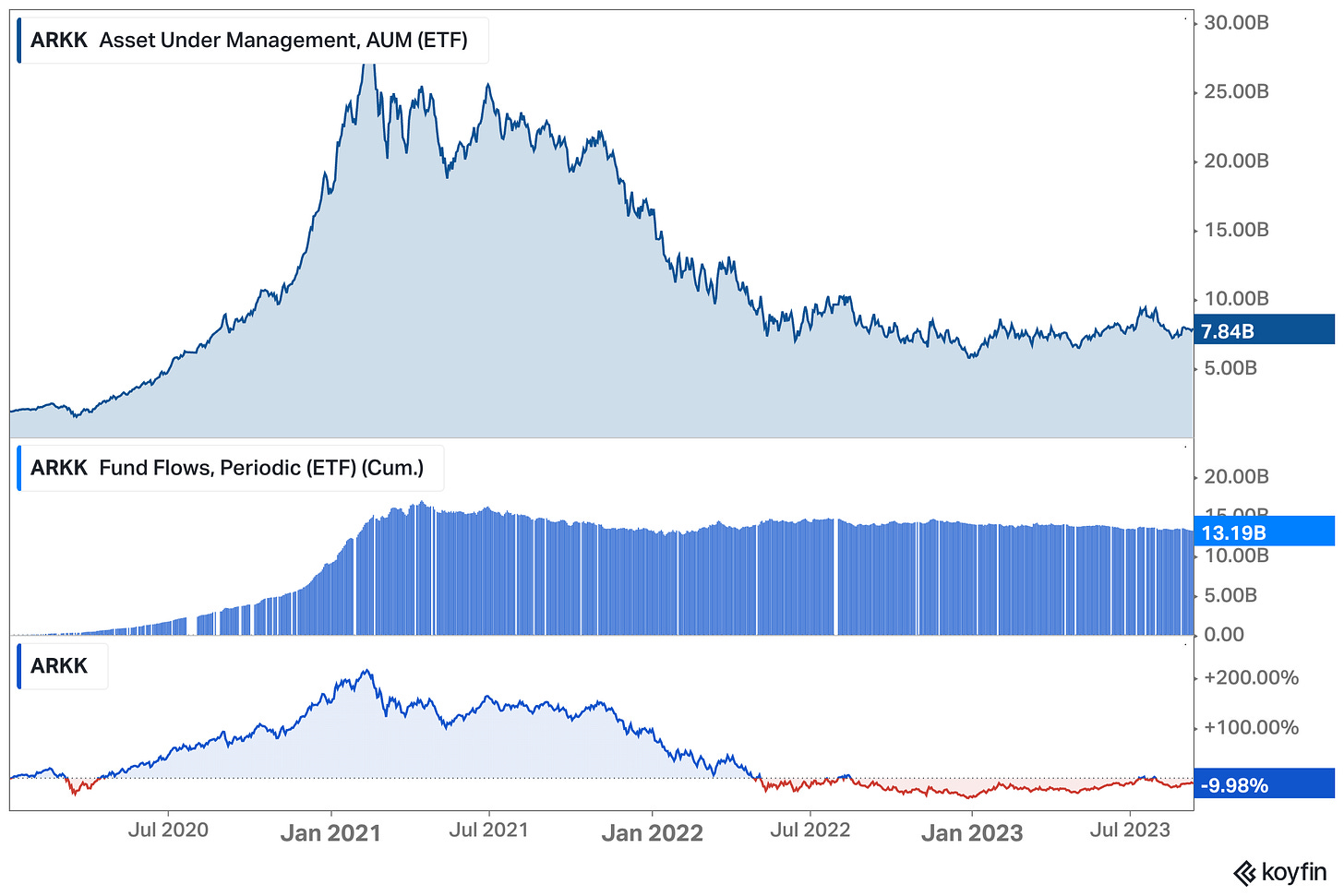

Thematic ETFs are one of the best demonstrations of the notion that financiers will literally build anything if they think investors are going to pay for it. Contrary to a mundane sectoral ETF which may cover everything that falls under the "energy” umbrella, a thematic ETF will invest in specific themes or prevailing trends. Themes like cloud computing, innovation, merger arbitrage, momentum, 3D printing, artificial intelligence, or luxury. Cathie Wood’s ARKK, a collection of “innovators” is a prominent example. Between 2020 and the fund’s peak AUM of $28.2 billion in February 2021, ARKK generated $15 billion in cumulative inflows. The fund is a little smaller these days.

There are inherent ironies in a thematic ETF. To capture the benefits of a rising trend, you need to get in at the ground floor; i.e., be early. By the time someone has constructed a financial instrument to express that theme, it’s likely already had its 15 minutes of fame. While the upside can be explosive when it works, the odds are usually stacked against the investor in a thematic ETF.

Stacked Odds

In essence, you are relying on; the theme being a winner, the fund being able to capture the benefits of that theme via its security selection, and the theme being nascent enough that it has not already been priced in amongst the representitive assets. It should come as no surprise that these ETFs typically miss the peak of their theme. Issuers tend to create thematic ETFs when the theme is at peak popularity. Investors, therefore, tend to buy thematic ETFs when they are at their peak and sell them at their trough. Usually, by the time it feels like a compelling enough opportunity to construct an ETF around a theme, it’s because it’s already popular. The chances of it being overvalued… is therefore higher.

“According to the academics Itzhak Ben-David, Rabih Moussawi, Francesco Franzoni and Byungwook Kim, the very worst time to buy thematic ETFs, which hold shares that follow a popular investment trend or theme, is when they launch. That is principally because the funds tend to launch just after the peak of their theme, and immediately before a steep fall in returns.

Emma Boyde, Financial Times, 20221

Kenneth Lamont, senior research analyst at Morningstar, suggests that “thematic fund launches are clearly a bull market phenomenon”, and remarks that “history tells us that the majority of those new funds won’t survive long enough to fully capture their chosen theme”. He is correct. Even if a fund identified a theme that would not fade into obscurity, one that would remain relevant, these ETFs have dreary survival rates. Morningstar shows that just 45% of funds launched before 2010 survived long enough to see 2020.

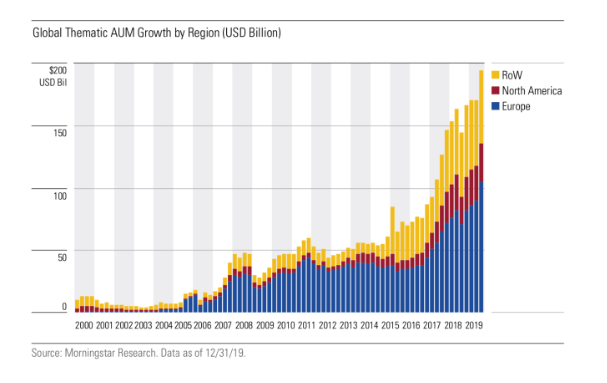

Even if you picked a fund with a winning theme, you could still fail to capture the returns if that fund is not well placed to harness that theme. More on that later, but the evidence shows these ETFs have grown in popularity over time.

Morningstar data indicates that the global AUM of thematic ETFs grew to ~$195 billion by the end of 2019. While this represented just 1% of total global equity fund assets, it’s up from 0.1% in 2009.

Not So Luxury

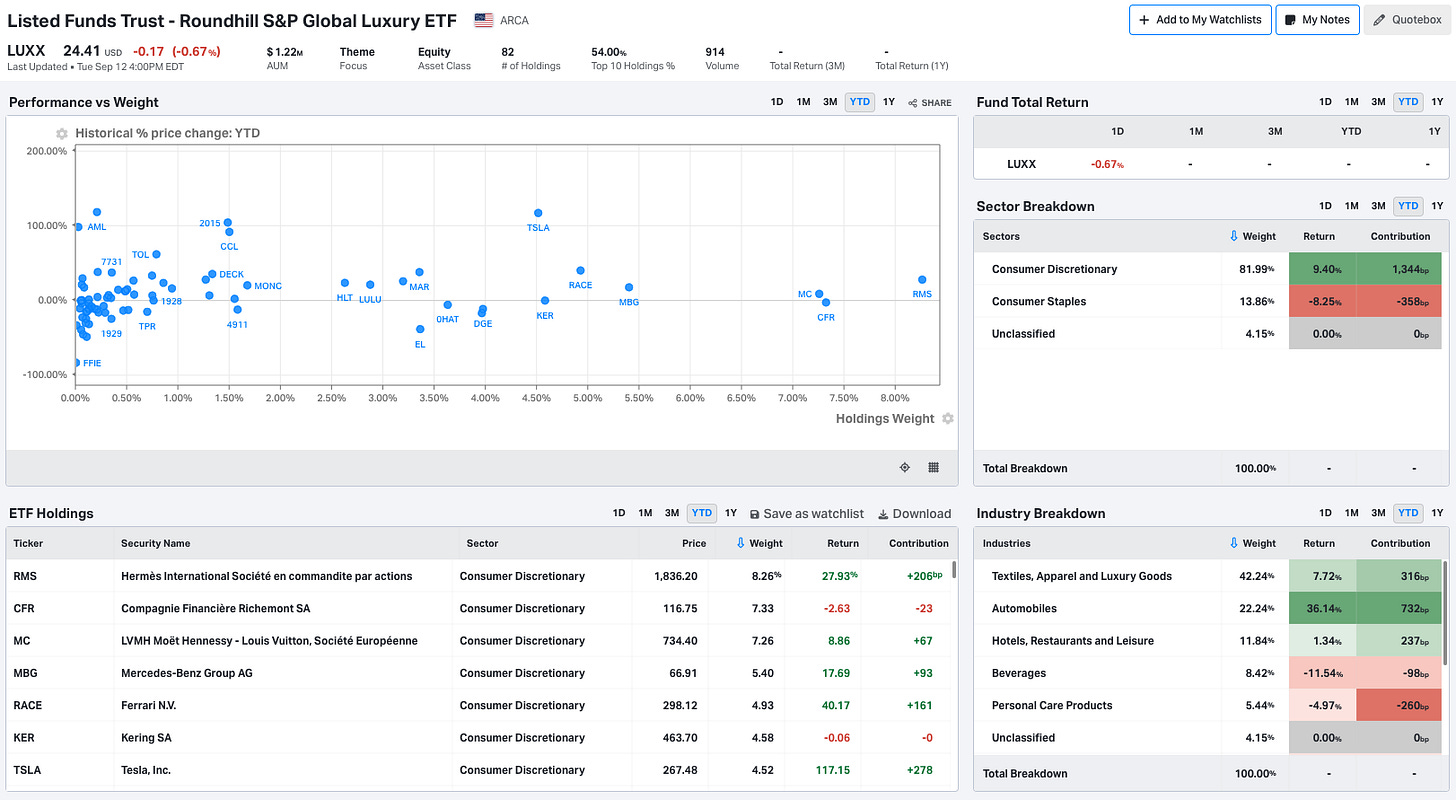

For the last few years, I’ve been studying luxury businesses. I have yet to pick up any material exposure in the space. There are a few names I am biding my time with but that’s another story. What caught my eye recently was Roundhill’s new Global Luxury ETF, LUXX. Having a look under the hood of their new thematic ETF was the impetus for this essay; because it’s so terrible.

The word “luxury” is defined as a state of great comfort or elegance, especially when involving significant expense. When “luxury” is used as an adjective, it implies that the noun it describes is luxurious by nature. In economics, a luxury good is one for which demand increases disproportionately as income rises; in other words, as prices rise, people desire it even more. In stock market terminology, the terms “luxury brand” or “luxury company” refer to companies that sell luxury goods. Genuine luxury businesses are sought after because they tend to be resistant to inflation and recessions due to their pricing power, fat margins, and affluent, price-insensitive, customers.

The problem is that “premium” and “luxury” are often used interchangeably. While I gather there is a level of subjectivity baked into these terms, products like Tesla, Lululemon, Ralph Lauren, and Nike, are not luxury. If your everyday Joe can afford one, it’s not a luxury good. Sleepwell Capital explains the levels of luxury well in this excerpt from his essay “All Hail King: How Rolex Exemplifies a True Luxury Brand Like No Other”2.

“Luxury is a spectrum. According to Brunello Cuccinelli, there are three types of luxury brands. If we imagine a pyramid, at the top is true or absolute luxury, in the middle is aspirational luxury, and the bottom accessible luxury. The top is where only the very best of breed sit and there are only a handful of them for any given category. Those that sit below can only dream of one day becoming part of that prestigious club. In the words of RH’s Gary Friedman, climbing the luxury mountain is incredibly hard, and has rarely been done. What separates the top from the bottom is having traced their own path for a very long period of time”.

True luxury brands are obsessed with quality and craftsmanship. They are purposefully exclusive and scarce. Their goods evoke status. While a Tesla may evoke some form of status, they are not exclusive goods, nor are they manufactured with the highest level of craftsmanship. They even occasionally lower pricing to stimulate demand; an action a true luxury business would not be caught dead attempting. While thematic ETF issuers might suggest there are hundreds of publicly traded luxury brand stocks worldwide, I believe the number is fewer than 30. Roundill believes there are ~82.

Below is a list of aspirational to true luxury companies. You will notice the gross margins are incredibly high for non-tech businesses; the EBIT margins too. The outlier, Ferrari has the lowest gross margin, but when compared to other automakers such as Mercedes (22%), Tesla (21%), BMW (17%) and Ford (10%), Ferrari’s 49% gross margin stands in a league of its own.

Including Ferrari, this basket boasts an average gross margin of 69%, an average EBIT margin of 23% and an average net margin of 15%. Comparatively, the holdings of LUXX have an average gross margin of 47%, an average EBIT margin of 8% and an average net margin of 0.1%.

While LUXX does house a number of true luxury companies like Hermes, LVMH, Ferrari, and Kering, the majority of the ETF is constructed of non-luxury companies with non-luxury margin profiles. Would you consider brands like Nike, Tesla, Diageo, Carnival Corporation, Lululemon, Rivian, or Lucid, to be luxury? I certainly don’t, but together they account for more than a fifth of the weighting. Interestingly, Roundhill’s logic in stock selection would mean a company like Apple ought to be in this ETF. It’s a premium product that evokes status, much like a pair of Lululemon leggings. It’s also beautifully crafted. However, when you realise there are more than 1.5 billion iPhones out in the world, you appreciate it’s not an exclusive product; in the same way leggings and yoga pants are not. To see Apple omissed is surprising. It’s correct, but surprising given Roundhill’s logic of seemingly surface-level, arbitrary, and subjective selection.

You may think that I am being semantic; but this is important because the way these companies operate, and the behaviours of their customers, are entirely different. During a moderate recession, it’s likely the typical consumer of affordable cruise line operators, premium athleisure, or consumer technology cut back on their spending. Conversely, the typical consumer at Hermes is more likely to be unaware there is even a recession going on.

Plot the fund’s holding on a scatter chart of gross margin by EBIT margin and you will notice that the majority of the shortlist I supplied earlier is confined to the upper right corner. The rest of the fund, with a few exceptions, is largely premium or luxury-adjacent. Now maybe this basket of stocks will perform reasonably well over time, but the thing that disturbs me is the fact it doesn’t align with the objectives of an investor looking for luxury exposure. The issuer’s prospectus claims that the fund’s objective is to “measure the performance of 80 companies engaged in the production, distribution, or provision of luxury goods and services”, yet this fund does not have the margin profile of a luxury basket. Meanwhile, they collect a 0.45% fee for constructing a portfolio that looks like the output of a ChatGPT query.

Another troubling sign is that this ETF was created in late August, 2023, a time when most of the world’s well-known luxury companies have already hit new all-time highs somewhat recently. Why wasn’t this ETF constructed a decade ago, before the incredible run in luxury companies that caught the market’s attention? Case in point.

Hypocrisy?

By now you might have noticed most of the arguments I am laying down are the foundations for the “anti-S&P” persona. Why on earth would an investor buy the market (an S&P 500 ETF) and do nothing? By investing in the S&P 500 you are buying America’s best and largest companies. You are also buying its worst and largest. You are committing to underperforming the index.

Surely if you could cut the S&P 500 down to only the best 50 companies and own them, you’d do better. I believe there is a fund that does exactly that. But the key difference is this. Investors in the S&P 500 are getting what they sign up for; low-cost exposure to the index. Investors in the Roundhill LUXX index are being sold something which is masquerading as something else. The luxury trend is well-established; it was a safe haven during the pandemic which later became roiled by a Chinese economy that took longer than expected to recover. Could there be a second wind from China? It’s conceivable, but history suggests that LUXX is yet another poorly timed issuance of a thematic ETF which will fail to capture the peak of its theme’s dominance. Some say that after the advent of credit, nothing spectacular has happened with respect to financial innovation. I disagree. While there has been a wave of new financial products hitting the market over the past few decades, financiers have consistently found innovative ways to earn their fees at the expense of the individual investor.

I want to conclude by saying this is not a criticism of Roundhill; although they do own a number of other… interesting… thematic ETFs that seek to capture alpha from themes like the metaverse (remember that?), sports betting, weed, generative AI, and… meme stocks.

If it’s the case that only one out of fifteen thematic ETFs turns out to be a humdinger then so be it. But I think if you possess the skillset to study companies and sectors individually, then you should consider avoiding the thematics and acquiring exposure to a theme the old-fashioned way; by doing your homework. At the very least, you should dig into the holdings of these ETFs and ascertain if you are content with how they go about managing their fund. Tema’s Luxury ETF, LUX, for example, is another relatively new fund. While it comes with an expense ratio of 0.75% which is 30bps higher than Rounhill’s, the construction of the portfolio is more aligned with what I’d expect to see in a true luxury ETF. Thirty holdings, and no Nikes or Lululemons in sight. The literature also shows more of an understanding of how to effectively identify a true luxury company. In other words, they appreciate3 how poor the construction of existing luxury indexes is. That said, time will tell how these funds perform.

Thanks for reading,

Conor

Honourable Mentions

Here is some other great stuff worthy of your time.

George Hadjia is the latest to break into the newsletter scene, with Birstlemoon Capital. The maiden report on Match Group is a pretty solid representation of the quality you can expect.

This Oxford Union address from LVMH’s Bernard Arnault was a rare public interview from the king of fashion and covered themes like defining luxury, stock market psychology, and more. Great watch.

Todd Wenning has spilt a lot of ink on network effects and moats. His latest piece on why network effects unravel is another solid read.

This new ~ real-time voice translation application looks insane. A future where miscommunication and language barriers are less of an issue excites me.

Deepsail capital with a succinct overview of why you should spend a little time studying microcaps.

An entertaining story from Howard Schultz, founder of Starbucks, about how Bill Gates’ father cemented Starbucks’ place in history, as well as the early acquisition and dealings between Schultz and the original Starbucks founders.

Lastly, the new share repurchase rules, set to roll out in Q4 this year, are going to be very interesting. Here is a breakdown of what companies will now be mandated to disclose.

Emma Boyde (2022), Thematic ETFs tend to launch just before a steep fall in returns, The Financial Times (here).

Excellent article! Thank you so much!