Timing is not everything, but it still matters

Waiting helps you as an investor and a lot of people just can’t stand to wait

“There is virtue in work and there is virtue in rest. Use both and overlook neither”.

- Alan Cohen

Most investors rely on the stock market to guide their decision-making

The investment industry is structured for activity— like a cacophony of overwhelming sensory cues streamed directly into your eyes, ears, and whatever orifice will accept them. The media encourages short-term thinking, reinforced by artificial constructs like calendar-year performance, quarterly earnings, and price targets. There is permanence in the questioning of why stocks move from day to day and ‘I don’t know’ is never a suitable answer— there always has to be a reason.

To feel comfortable doing nothing, when everyone else appears to be doing something, is to swim against the current. Doing less is a constant cognitive battle and most people fall victim to the market’s siren call at some point.

“Waiting helps you as an investor and a lot of people just can’t stand to wait. If you didn’t get the deferred gratification gene, you’ve got to work very hard to overcome that.” - Charlie Munger

Suppose we can glide between dimensions for a moment. Company A reports a mediocre earnings report— in line with expectations, nothing better, nothing worse. In the first dimension, the stock falls 15% the next day. In the second dimension, it finished the day up 5%. This experiment would not exist in a vacuum. Expectations - one of the myriad factors that can influence post-earnings reactions - will play a large part here. But on the whole, assuming all else equal, the investor is more likely to attribute a negative opinion of the report in dimension one (-15%) and a positive opinion of dimension two (+5%).

Why is this?

This thought experiment illustrates a fundamental truth— most investors use the stock market as a barometer to validate their opinions and decision-making.

A child sitting an exam may feel unconfident about their answer to question 17. Leaning over at their peer’s papers, they glimpse at what they wrote for question 17. Alas, it’s the same answer. Instantly they feel reassured and more confident— unbeknownst to the fact they both provided the wrong answer.

In the worst of outcomes, an investor will glimpse at a post-earnings price reaction before establishing their viewpoint— therefore tainting their perception and reinforcing a framing effect. That is to say, the report will now be consumed with an innate bias and the reader will subconsciously seek out confirmatory information.

In a marginally better outcome, an investor will glimpse at a post-earnings price reaction ex-post— seeking validation on how they perceived the report vs. how the market did— often affording the market’s reaction too great an importance.

There is merit to keeping a pulse on the market’s viewpoint, however. The impact of having a contrary opinion, and putting capital behind it, can be significant in the short to medium term. One need only look at the explosive turnarounds in previously beaten-down large caps like Netflix and Meta Platforms as corroborating evidence. It goes both ways too. Every bubble must come to an end and for a small number of investors who get the timing right, they capitalize on going against the crowd.

However, as the time horizon grows this can exhibit diminishing importance.

While timing is not everything, it still matters

In the summer of 2015, you could have looked at Greggs Plc— a company the market clearly favoured, having risen 290% (14.6% CAGR) over the prior decade. Since the summer of 2013, the stock had gone nowhere but up. Sure, it was a little expensive at the time, but it wouldn’t have been contrarian to own Greggs. If you’d bought at the peak in 2015, it would have taken two years to break even (evidence of being paid to have a contrary short-term outlook). If you’d held on, you would have enjoyed a 10.8% CAGR until the end of 2024.

That CAGR would be chopped down to 7.4% at today’s share price after some negative reactions to management’s commentary on the UK’s 2025 economic outlook at the beginning of the year.

Earlier I mentioned that “as the time horizon grows [timing becomes less important]”. I generally believe that to be true— with caveats. Being long consensus longs is fine, but it is the entry point that will have the most profound influence on long-term return. This is where having a shorter-term perspective can be critical. In the two years following Greggs’ 2015 peak, the forward earnings multiple tumbled from 25x to 15x. If you had waited until the market fell out of love with Greggs and still believed in the long-run opportunity, your return would be closer to a 13.4% CAGR today—or 17.7% by the end of 2024. This underscores that even if you are investing for the long term, the entry price matters. To increase the chance of a favourable entry price, you must engage in short to medium-term thinking. Buying at any price is generally a flawed philosophy— patience to wait for better entry points is typically awarded.

The point I am trying to make is that timing only becomes ‘less’ important, not unimportant.

There is a spectrum. At one extreme there is the ethos of ‘buy only when it trades like it’s going bankrupt’. At the other extreme ‘buy quality at any price’. I believe that the former is arguably more prudent, but requires an incredible amount of patience and likely results in a great deal of lost opportunities— great businesses seldom trade in such a way and it can be enough to acquire fantastic businesses at good or fair prices. The latter can work out but in my opinion, it’s a bolder testament to the fact you are complacent with playing the odds (that are seldom in your favour)— many people like to cite tremendous outliers, the one in 10,000 stocks, as evidence to the contrary but that mentality, for most unfortunate souls, is a recipe for disaster.

You can do very well existing somewhere in the middle of that spectrum— buying quality businesses at fair prices with a long-term horizon and a disciplined process. For the sake of longevity, this approach ought to be beneficial for the common investor. That said, there is no single way to invest, as evidence suggests people can make it work with whatever process is most compatible with their temperament.

I digress.

An investor looking at the market reaction to an earnings report commonly does this as a validation process— “I think X and the market thinks Y, so I am wrong”. While short-term price reactions are useful in some contexts, they are not indicative of truth. After all, it can be tremendously profitable to have a differing opinion from the market and have that opinion justified over the long term. But you have to be right. You can’t expect to be blessed through a strict adherence to patience alone.

This tendency to seek validation from market reactions reflects a deeper human inclination for fairness and reassurance. Whether we know it or not, we seek that reciprocal behaviour in the stock market. As Shakespeare once said, “The quality of mercy is not strained. Upon the place beneath. It is twice blest: It blesseth him that gives and him that takes”.

The pseudo-relationship between market and man is different. The stock market does not show mercy, nor does it benefit from showing it. Unlike in human interactions where mercy can be mutually beneficial, the market is void of compassion. It neither offers leniency nor rewards it.

Why are we bad at selling?

In 2024 I set myself a personal goal to be less active— further insulation from talking heads and to reduce transaction frequency. These two things can go hand-in-hand, as discussed in the introduction. Selling can be the result of pressure, but there are various reasons why we tend to be ‘bad’ at selling stocks.

An article1 from Frank Thormann at Schroders in 2022 was aptly titled ‘Why most investors are bad at selling and what they can do about it’. Referring to the underperformance of active managers, Thormann highlights the damning findings from a 2016 paper by professors Jin and Taffler:

“In a landmark paper, Professors Jin and Taffler (2016) looked at a large sample of over 3000 fund managers over the period spanning from 2003 to 2013. They found that on aggregate buying decisions added 1.4% of outperformance per year, while selling decisions detracted -1.8% annually in underperformance”.

The article describes a handful of biases that work against us humans in the pursuit of selling investments. Thormann surmises that because our brain processes fear and greed differently and the presence of behavioural biases, we are at odds with successful decision-making in this matter.

“Emotion of fear is processed very differently in the brain from the opposite feeling of exuberance because it is processed in a different location. As a result, humans think of (financial) losses very differently to how they think about gains, leading to suboptimal decision-making”.

This question of why we are bad at selling has been studied copiously, such as in Akepanidtaworn2 et al‘s 2018 paper, Selling Fast and Buying Slow, where they conclude that “while investors display skill in buying, their selling decisions underperform substantially—even relative to random-sell strategies”. Also observing institutional investors, this paper used a dataset of 783 portfolios, averaging $573 million in AUM, and covering 4.4 million trades from 2000 to 2016. Employing counterfactual portfolios that used a random selling strategy as a benchmark, they found that genuine selling decisions, made by managers, underperformed by 80 bps annually. Conversely, the genuine buying decisions outperformed the random counterfactual portfolios by 100bps annually.

Both the article and the paper conclude that selling is a neglected skill amongst institutional investors and point to various behavioural biases as a cause. Thormann, the author of the Schroders article, lists commonly understood biases— a summary of which is bulleted below.

Loss aversion: “The tendency to allow very recent performance history to shape one’s risk assessment of an investment”.

Availability bias: “In complex decision making we do not consider all alternatives equally but quickly jump to the ones which come to mind first”.

Confirmation bias: “We have a strong bias to interpret subsequent data points in a way to appear favourable to our original premise”.

The final point he makes is that we tend to spend more time on buying decisions than selling. Just think about it— how long do you spend researching a business before you end up deciding on whether or not you will buy it?

You examine the industry makeup, the market structure, and the business model. You scrutinise potential tailwinds & headwinds, cost structures, unit economics, and the consumer. You dissect the financials, the filings, and the management. You might reach out to peers to hear their take. You should explore confirmatory and contradictory evidence to challenge your base case. You go through numerous stages and burn a considerable amount of time.

Now, think about how long it takes you to decide to sell a stock. If we are being candid, for most it’s not weeks or months— it’s a matter of days. In some cases, hours. Again, there is a spectrum. Act too hastily and you might let an overreaction turn into a mistake. Conversely, sometimes fast reactions can help with calamity avoidance— it’s a good choice to jump out of a nosediving aeroplane while you have a parachute.

The same outcome can be framed in a different light. On the one hand, being methodical and taking time to process information can avoid making an irrational decision of selling pre-emptively. Yet, spend too long pontificating on the details and more damage may be incurred.

I’ve encountered this challenge many times— where the mistake wasn’t exclusively the sale, but the buying decision that preceded it— where the correct buying decision was not to buy and the correct selling decision was to sell 5 seconds after buying. Years ago, I bought into the premise of the PLBY Group squeezing value out of a brand that time had forgotten (Playboy). There was an opportunity for high-margin licensing and company-operated distribution of products and services. Eventually, the red flags compiled and I realized this thesis was not going to play out. I sold my relatively small, speculative, position for ~$6 per share with a 50% haircut. It was the right selling decision in the grand scheme, but it came far too late. The silver lining here was that I was not more hesitant. Within a year or two, the shares fell to $0.50 per share— I had avoided a 96% drawdown. These are relatively inexpensive lessons at my age, and I am grateful to have learned them early.

Investors are rewarded for both action and inaction

It’s natural to circle back to the buying decision when thinking about selling. You might think to yourself ‘If the buying process is perfect you can worry less about the selling’. The reality is that nobody has a 100% hit rate. Every investor will hold a future stinker at some point in their lives— the future is unknowable so what might seem like a strong bet today may require folding tomorrow. But suppose you have divine luck and throughout your life, you manage to exclusively acquire companies that will, at some point, proceed to 100-bag.

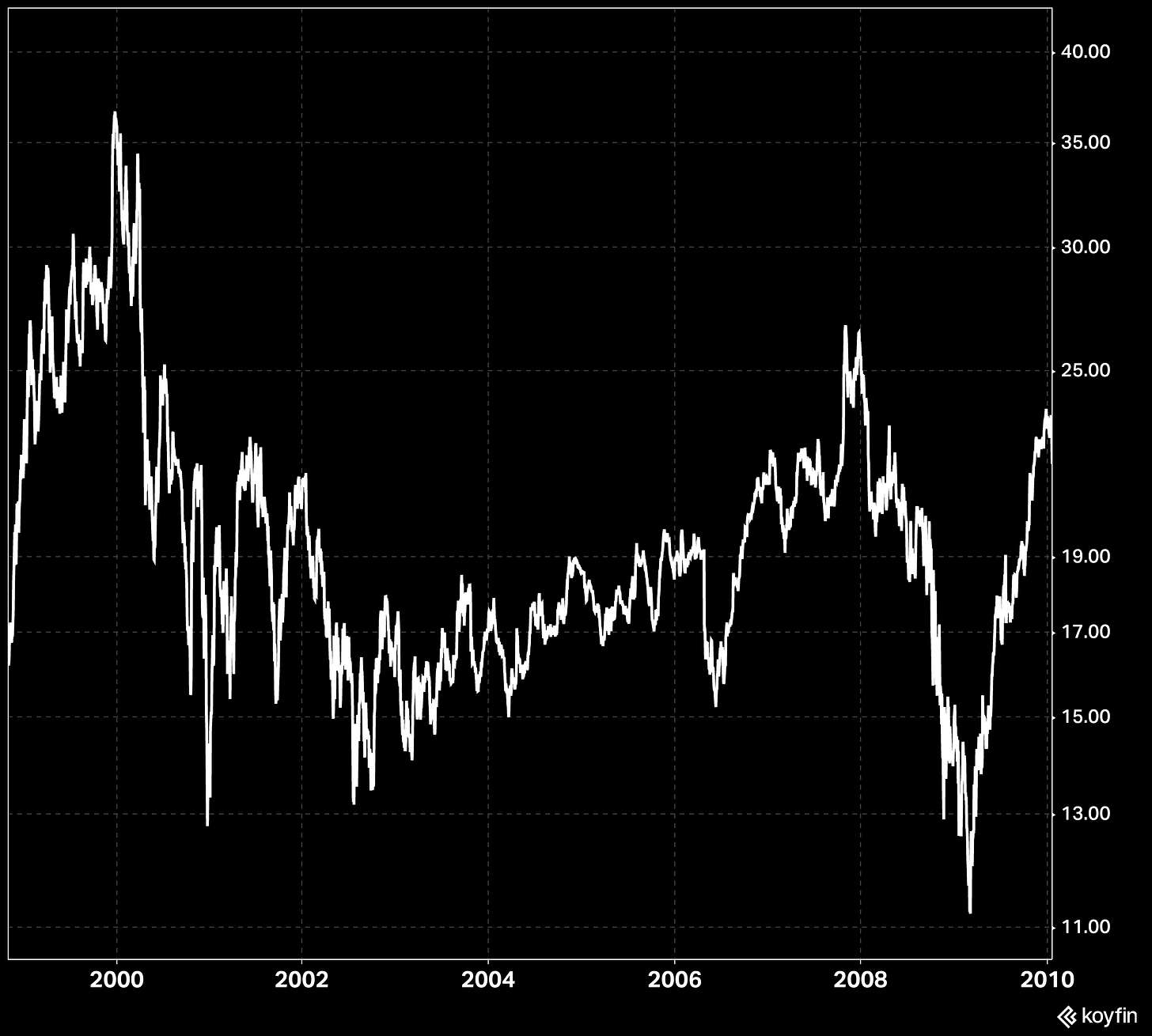

At some point, every 100-bagger has a chart that looks like the ones I have shared below (with legends and labels removed for dramatic effect). You are likely to suffer multiple significant drawdowns, years—even decades— of somewhat flat performance, and uncertainty as leaders, consumer tastes, regulation, and business models evolve. In short, regardless of your hit rate, you are going to be challenged with sell decisions. It’s guaranteed.

The market’s short-termism is dictated by sentiment and while timing is not everything, it still matters. I believe that selling is harder than buying, due to the increased influence and quantity of biases. While buying and selling share similar biases (such as FOMO), the introduction of live, unrealised profit and loss, creates a greater sense of urgency and desire to act.

My experience thus far has taught me that purposefully reducing potential triggers to the biases mentioned in this text can go a long way in removing emotion-driven sell decisions, but it won’t absolve them completely.

Errors at the input stage (buying decisions) are like ticking time bombs that, even absent of external stimuli, sit and wait for the self-awareness that you were wrong. The irony is that you can’t know if a buying decision will have a poor ten-year performance on day 1. This is only possible with time.

Investors are rewarded for both action and inaction. The challenge is knowing when to apply each. The desire to tune out of the market hubbub and transact less frequently is not an intent of disengagement— rather, a step towards better decision-making. It’s not about never acting. It’s about acting when it matters most.

Thanks for reading,

Conor

Hi Conor - we featured your excellent article in our weekly newsletter to friends, partners and clients --> https://278773.seu2.cleverreach.com/m/15968686. Thanks for your excellent work !

I'm glad there's solid evidence behind the idea that selling decisions are usually worse, because this has always been my personal Waterloo.