An 'Acquired' Taste

And how the search for nuance can enhance perception

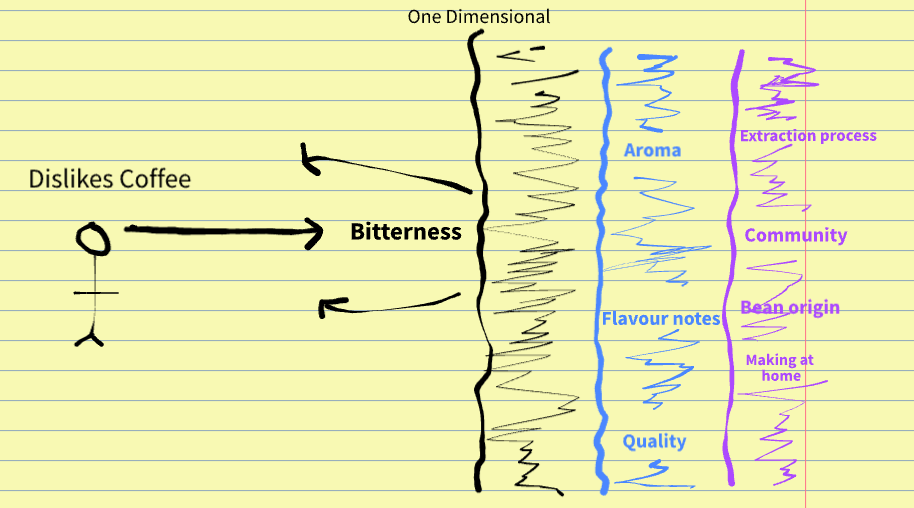

To a person who doesn’t like coffee, all coffee tastes bad. A regular drinker of coffee can probably tell the difference between a good and bad cup of coffee. Someone like me, who has dipped their toe into the rabbit hole of coffee, acquiring an espresso machine and bean grinder, might be able to tell the difference between a great and good cup of coffee. Beyond my comprehension, there are additional layers of nuance that I do not understand - the importance of bean origin, advanced extraction techniques, the geopolitical landscape of coffee, etc. I am unlikely to tell the difference between a great and an exceptional cup of coffee. They probably taste the same to me. Advanced connoisseurs could identify the difference in the blink of an eye.

As humans, we often ask “Why does that person care so deeply about that thing I have no interest in?”. The analogy of ‘going down the rabbit hole’ is a great one for describing interests. It illustrates that there is depth, acknowledges that it’s a journey, and conveys that there is a point in time when the subject has yet to go down the ‘hole’. At this stage, they stand at the surface level. Holes tend to be dark. You can’t see what is at the bottom. The darkness represents a litany of unknown unknowns. These may become known unknowns, and eventually ‘knows’ as an individual ventures further into the rabbit hole of their chosen interest.

This phenomenon, of not knowing what there is to not know, is why we find it hard to understand why people like certain things. Put another way, without going through the rabbit hole ourselves, we don’t know what there is to appreciate. There is a layer of nuance that is locked away from our understanding. This information asymmetry between two parties can be a learning opportunity; where one enlightens the other. The uninformed party need not develop a sense of mutual appreciation, however. But a little understanding goes a long way.

More often, it results in conversations that provide no value to either party. This happens often in the investing world. Sometimes, two informed parties have opposing views; engaging with one another with no intention of understanding the other’s perspective. Other times, an uninformed party will engage an informed individual only to share their uninformed opinion. In the investment business, they are referred to as armchair analysts. Distractions that ought to be ignored.

When you find yourself in a situation like this, conversing with an individual who simply likes the sound of their own voice, I have two anecdotes for you to fall back on.

There is this great anecdote about a guru and a gentleman. “What is the secret to eternal happiness?”, the gentleman asks. “To not argue with fools”, the guru replies. “I disagree”, remarks the gentleman. “Yes, you are right”, replies the guru.

If the other party in a conversation only seeks to be combative and make the point they want to make. The saying goes that you never wrestle with a pig because you both get dirty and the pig loves it.

Acquiring a taste

Those familiar with the expression, ‘an acquired taste’, might assume repeated exposure to something eventually leads to an appreciation of some variety. With food, the idea is that by consuming a flavour again and again our taste buds gradually come to like the flavour. Or at the very least, tolerate it. The expression extends beyond food and can be used to describe someone’s personality, a style of investing, a sport, or just about anything else that divides opinion.

From childhood to adolescence I despised coriander (cilantro). I have this blurry memory of being sat at the dinner table one evening as a child. A steaming bowl of what I can only remember contained pak choi, beef, and coriander, was placed in front of me. As I leaned over my plate, a thick, hot smog of coriander coursed through my nose, causing my throat to swell as my body rejected it. I fail to recall exactly what repulsed me so much, but it resulted in my avoidance of the herb for years. That was until my early 20s. I started dating an Indian girl and a hatred of coriander would prove to be awkward. I decided that, gradually, I would begin to experiment with it again. The dish that helped me overcome my trepidation was a sweet chilli salmon fishcake recipe. I started grinding coriander into the cakes and eventually started to appreciate it raw. Now I love the stuff and sprinkle it over everything.

Most people assume that our tastebuds adapt to new flavours and this is why our tastes can change. This is only partly true. Taste preferences can be genetic. They can be the result of our environment. Studies have shown that our tastes can shift based on the preferences of our idols or social groups. Repeated exposure can also decrease our sensitivity to initially off-putting flavours. These forces are particularly malleable at an early age. It’s common for babies to pivot from eating everything to becoming pickier as they mature. Coincidently, this coincides with the “no” phase that children commonly go through.

Another perspective on why tastes are ‘acquired’ stems from our ancestry. Our internal defence mechanisms are wired to initially reject certain flavour profiles through fear of contamination. Commonly, bitter flavours due to their association with poison. Think about the following flavours and the first time you tried them; coffee, dark chocolate, grapefruit, hops (used in beer), tonic water, green tea, kale, brussel sprouts, and turmeric. I remember my first beer1, it was a Becks. Sitting in the conservatory on a hot day, somewhere between 13 and 14 years old, I stole a sip of my dad’s beer. Suffice to say, it was unpleasant. Most people’s experiences with the aforementioned flavours were unwelcome at first. They may still dislike them.

Before a taste is acquired, our brain has not formed the necessary associations to help us appreciate alternative dimensions of flavour. For coffee, it might be that all we taste is bitterness. Over time, with repeated exposure, our neural pathways can adapt, leading to a reduction in the perceived bitterness and an increased perception of the complex flavours and aromas.

I think about it as the brain breaking through the barrier and unlocking the sensations previously invisible to us. Once you get past the bitterness of coffee, you may come to develop an appreciation of flavour and aroma. Other factors, which extend beyond the acquired taste, may include a richer understanding of quality and extraction, the satisfaction of community, and so on.

How the search for nuance can enhance perception

There are similarities between acquiring a taste and learning about a subject. In both cases, persistence results in increased perception. When someone likes a subject, they go down the rabbit hole and appreciate the nuances more. It’s like the cocktail party effect. You’re at a party, it’s busy. There is music playing, and there are groups of guests discussing amongst themselves. You don’t hear what the other guests are saying because you are so preoccupied with the discussion in your social sphere.

“The cocktail party effect is the name given to a phenomenon describing the brain’s ability to tune out the noise at a party and focus on the person’s voice with whom you share a conversation. The ability to focus one's auditory attention on a particular stimulus while filtering out a range of other stimuli. Should a [new] member enter the conversation, then you would focus on them too, because you are no longer filtering them out”.

When a new interest comes into your life, it plays the part of the new member of the social circle. Your perception of matters related to that interest is enhanced to the point where you take notice of or absorb, information that you previously would have filtered out. This also has a resemblance to the Baader-Meinhof phenomenon or frequency illusion; when something you recently learned about or noticed suddenly seems to appear everywhere.

Connecting this back to the points I made at the outset of this article, I draw two important conclusions.

Avoid confrontations with people who have not attempted to acquire a taste for a subject matter

This isn’t my way of saying avoid people who don’t share the same interests as you. People have different perspectives, and that’s fine. It can be beneficial to hang around with people who have different interests, opinions, and ideas. This helps avoid GroupStink. Concerning investing, I am referring to the engagement with people who have strong opinions on matters they have done no legwork on. The armchair analysts. It’s not a waste of their time; they seek to elicit responses and attention. But it’s a waste of your time. Without having ventured into the rabbit hole their perception of the subject matter is as limited as the first-time coffee drinker who can only taste bitterness. They have not yet unlocked a nuanced perspective.

This is a powerful tool to understand for the investing process

This effect of heightened perception succeeding an admission of interest or exposure is something I suspect many of us are already aware of; whether subconsciously or consciously. Nonetheless, it’s a powerful ally to a lifelong pursuit of studying companies, industries, management teams, and market structures. The notion of a circle of competence is a good idea. Stay largely within the confines of your areas of understanding. The circle ought to be expanded over time, however. Venturing into a new industry can be daunting. It’s important to accept that there will be nuance far beyond your comprehension as an outsider. At the same time, we know that our perceptual abilities will strengthen over time with repeated exposure. The stimulus to that is getting started.

The longer you invest, the more rocks you turn over, and the more you learn from mistakes, the sharper your perception grows over time. As a twenty-something with decades ahead of me, this is something that excites me. If you are a curious person, keen to understand the inner workings of sectors and industries, then it ought to excite you too.

Thanks for reading,

Conor

great take, thank you!