The Reality of Mixed Reality

Yet another take on Vision Pro and mixed reality

The following passage is an excerpt from my second, smaller, newsletter called Notes to Self. Please bear in mind that these are opinions loosely held.

Yet another take on Vision Pro and mixed reality

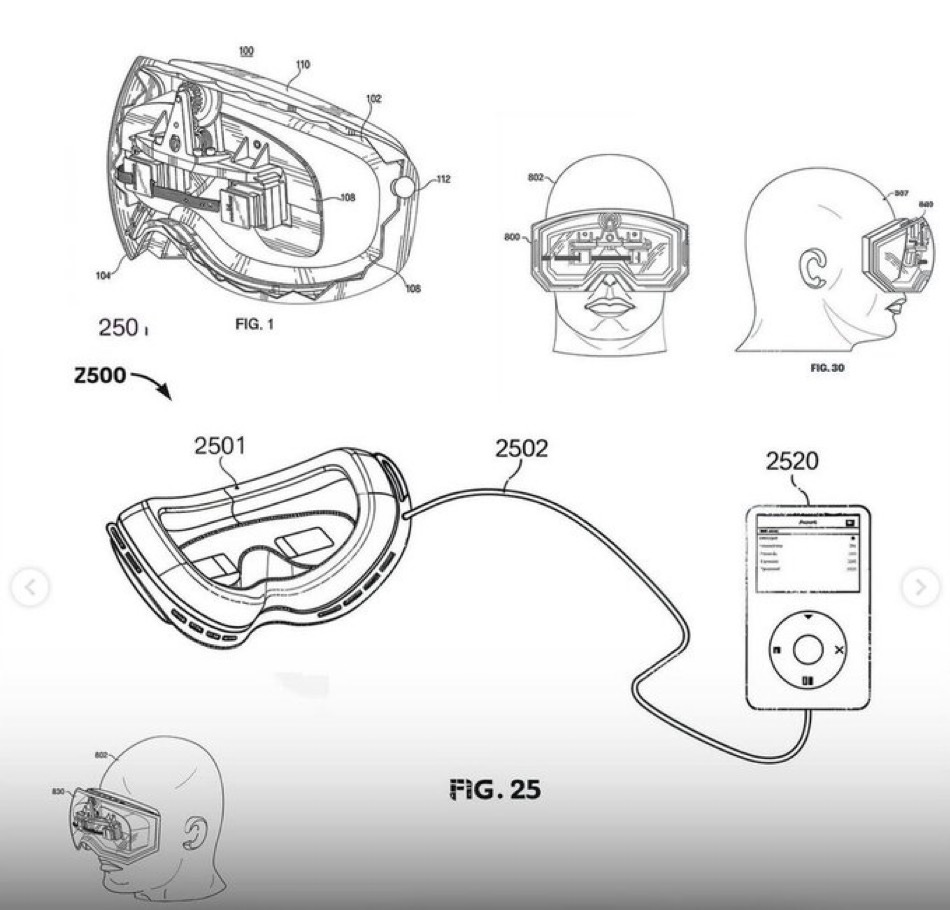

The world does not need another opinion on the Vision Pro, the Apple mixed reality device whose launch coincided with Meta earnings, but I will share mine so I can understand my thought process in the future. I have the right to be wrong. The revenue share of Meta’s FRL is so small it might seem redundant to give it so much limelight. But, directionally, it’s an important category for the company. With a launch of this scale, the hyperbole and sensationalism rhyme with things we’ve seen in decades past. It’s natural to be sceptical of new technologies. While I say “new”, this industry is hardly infantile. Meta has been pioneering1 it for the last decade. Apple has been thinking about it since at least 20072. It’s had traction, but not mainstream traction. Many speculated that Apple’s entrance would be a litmus test for mass market viability. The attention it has garnered thus far has been compelling, but it’s still too early. The form factor will change, the technology will improve, economies of scale will occur, and the understanding of the value and side effects of these devices will improve; albeit I think the latter will occur with some delay.

I happen to be in a camp that believes some form of mixed reality will play a large part in the future. I don’t believe it will look like it does today, however. Early iterations of computers, smartphones, and the internet had defects. You can think of them as first-generation defects; inefficiency, cost, lack of adoption/network, they look stupid, they sound stupid, they don’t quite work perfectly. But each of these had something so special in the way they resonated with humans that we persisted with them. Resources, understanding, talent, and technology, all worked to smooth out those edges. Today these are thought of as commodities that just run smoothly and are a fabric of life itself; seldom do people stop and marvel at how insane it is to have a supercomputer in your pocket. I believe that mixed reality has that special essence, and we are at a stage when this is not obvious to the majority. Likened to the evolution of the mobile phone, today’s devices are closer to the brick than the first iPhone.

Some fear the social ramifications. Society has already begun its descent into online addiction and the Vision Pro looks likely to amplify the factors that have kept our dopamine receptors well-fed since the adoption of smartphones. Technology moves faster than legislation. Being the terrible forecasters that we are, it also moves lightyears ahead before we have a chance to reflect on its consequences to society. Our delayed appreciation of the harm of social media usage has tainted our perception in that way. We fear the worst. I happen to fear the fears that we don’t know we ought to fear. I could pull up newspapers by truckload that highlight the inaccuracy of consensus from innovations-past. Like how the hand-held phone was a niche product for business purposes, or that the internet would fail to catch on. Conversely, I’d also find articles outlining how we will all move around on segways, use 3D televisions, and so on. It goes both ways. The mixed reality segment is particularly interesting because we’ve already seen failed iterations in the past. The Google Glass, launched circa 2013, was an AR experiment that failed to catch much steam. Its failure is a common rebuttal to the idea that humans will someday overlay augmented data before their eyes.

Perhaps it was ahead of its time; a great idea without the necessary technology and public understanding to make it viable. Perhaps decades down the line, we will look at Google Glass as the brick phone and the early headsets we see today as more of the slightly more evolved Nokia handset. The point is that the presence of past failure doesn’t necessarily imply future iterations will fail. Humans are conditioned to think in these terms, however. We are pattern seekers. With hindsight, we can see that even during the adoption phase of successful technologies the trajectory is a cascading series of doubters-turned-believers. I find a great sense of irony in individuals who remark on how stupid commuters look with Vision Pro headsets strapped to their faces. They look just as stupid and depressing as a packed London underground might look during rush hour; where every passenger is deeply engrossed in their own virtual reality within their phone. Humans have a great affinity for self-deception. “That will never be me”; until the moment it is.

The reality is that nobody knows. At this stage, speculation rules the roost, on both sides. One side is overtly optimistic, thinking only of the potential, with little consideration for the downsides. The other side is dismissive, closed-minded, and primarily concerned with how foreign these objects are and how they may harm society. If framed under the nuances between fads and trends, I believe that mixed reality represents more of a trend that may become sustainable. As I noted in “Fads and Second Acts”:

Fads arrive quickly and dissipate: A fad is a fidget spinner. We can define a fad as an object or behaviour that achieves short-lived popularity and then fades away. Often catalysed by excitement, emotion, or social influence, fads are seldom born from functionality or necessity. More style, less substance.

Trends stick around: Trends tend to get strong over time, persist longer, and solve problems. Contrary to a fad, trends are not a “moment” they are a “movement”. Trends are born on the foundation of functionality. They are not perpetual, however. While they stick around longer than fads, they are susceptible to obscurity.

Sustainable trends have a second act: Trends can dissipate too, but what separates a trend that persists for 3 years from one that lasts 3 decades? How does one feel comfortable investing in a trend without knowing if it has legs?

In this regard, mixed reality has been around too long to be a fad. It might become a trend that eventually dies out but what interests me is that there is a genuine foundation of functionality inherent in this market. Individuals can do things with mixed reality that they can’t do anywhere else. Whether that proves to be a sustainable trend with a “second act” remains to be seen.

What interested me is that Apple has come in as a price setter. The Vision Pro costs in the vicinity of $3,500 to $4,000. This is the level through which all future generations will be watermarked. The presence of the “Pro” nomenclature implies that future generations will see a cheaper base model of Apple’s Vision line. In contrary fashion, Meta optimised their Quest line to be as affordable to the common consumer as possible. Under Occasm’s Razor philosophy, you’d suppose that this evolves into a similar dynamic to the iOS and Android competition.

What is exciting from the perspective of an Apple shareholder is that we are seeing the birth of a first-generation product; and all of the ugliness that comes with it. Not since the AirPods in 2016 have we seen a potentially multi-generational product from Apple. Before that, the Apple Watch was launched in 2015. People argue about the revolutionary nature of these two products, but the iPad (2010) and iPhone (2007) are uncontested, and date back further still. For years we have seen, even been bored by, Apple’s product line-up. Each year we see perfect products3, with an incremental amount of additional perfection added-on. Mature products with a level of quality consumers expect. The Vision Pro is exciting, but it has those imperfections of a first-generation offering; it’s too heavy, the app library is limited and not yet optimised for Vision Pro, it’s expensive, etc.

I have experience using the Meta Quest models. I have not yet experienced the Vision Pro in person. But from what I can tell, Apple has delivered the critical feedback of “You put it on, and it just works”. For Apple users, this works because of its connectivity to the ecosystem, the familiar yet new UI/UX, and the software. Not to mention that Apple’s specifications for this device outrank the Quest 3 (reminder that it does cost ~7x more). For all the want and desire of a “killer app” it might just be that the Vision Pro’s ecosystem is what entices customers. In theory, the Quest 3 does 90% of what the Vision Pro does at a fraction of the price. The same argument can be proposed for a Honda Accord and a Porsche 911. But let’s not forget there was a lot of hype surrounding the Quest 3 launch last year. Albeit, not to this scale. As a lifelong Apple user, in these last few weeks, I feel I gained perspective on how annoying it can be to see Apple fans salivate over a product which is only marginally better/worse than, say, an Android device. That’s brand power for you. You can imagine a hypothetical future where people remember Apple as the pioneer in mixed reality; ignoring the decades of progress that came beforehand from the likes of Meta, Oculus, and others.

Hypotheticals aside, the understanding of the mixed reality market is sparse amongst the general public. Virtual reality (VR) can be thought of as the more deeply immersive variety; often demonstrated through gaming, and simulation, and may include hand controllers (which I think will be phased out eventually). Augmented reality (AR) enhances what we see by overlaying information, graphics, or other elements in the real world. Mixed reality blends the two. Early Quest models were almost entirely VR. The concept of passthrough, a feature that allows users to see the real world around them through the headset's cameras, was greatly improved in Meta’s Quest 3. Pass-through is subject to latency; because the cameras still need to process what they are seeing into the display. Today, while the Apple pass-through is superior, both headsets offer comfortable experiences in this regard. If technology has taught us anything it’s to expect to be surprised. A few megabytes of memory once occupied an entire room of a building. Today you can squeeze one terabyte (1,048,576 times larger than a megabyte) into an iPad. We have a hard time finding comfort in unknown unknowns.

In the scenario where this technology becomes a larger part of society, the Vision Pro will increase the attention this space garners from consumers. This should increase the demand for lower-cost alternatives like the Quest 3. In turn, as developers are attracted to the space this increases the likelihood we see stronger applications which further improve the value proposition of owning a device. Apple is a methodical company. Their track record illustrates that when they enter a market, they intend to dominate it. For them to believe there is compelling evidence to invest in what they define as “spatial computing” bodes well for the industry.

As far as who wins, you might as well ask me how long a piece of string is. I have no idea. As for when/if it becomes mainstream, I also have no idea. There are bound to be twists and turns. There are sure to be ramifications and unimaginable benefits. I think there is a lot to be excited about. But I also believe if this does happen, it won’t happen all at once. Hindsight has the habit of making technological advancements look like they went from 0 to 1 overnight. When in reality, they are often long and drawn-out processes packed with failure and iteration.

Thanks for reading,

Conor

Using this term loosely, because Meta acquired their way into this market, and the early seeds of this market were not planted by Meta.

Apple filed a patent in 2007 that laid the groundwork for the technology used in the Vision Pro. This early patent included ideas for a headset that could display media like movies and sports events in a virtual reality setting, with features like a simulated movie theatre experience. It also described a device that would respond to head, eye, or hand movements to adjust the media display, providing an immersive viewing experience akin to being in a stadium.

Not in the literal sense. Rather, mature and well-established products that have a level of quality people expect

The original Apple II computer was $1298 in 1977, and you had to buy a monitor and floppy disk drive as "extras". That was over $6,000 in 2024 dollars. The Vision Pro is reasonably priced by historical standards for niche products that break a technological mode and mold. The question is if it will gain traction with early adopters who find ways to use it to solve their problems.