The Bit In The Middle

Purpose, desire, and being present

All my life, I've been searching for something. Something never comes, never leads to nothing. Nothing satisfies but I'm getting close. Closer to the prize at the end of the rope. All night long I dream of the day. When it comes around and it's taken away - Dave Grohl

Same, but different

We have voiced the same mortal dilemmas for hundreds of years; most of them influenced by our longing for purpose. Though centuries of unimaginable progress have endured and awareness of how our biases & environments shape our way of thinking is at an all-time high, we still fall victim to the same anguishes as our predecessors. We all just want to be happy and fulfilled; the byproducts of purpose. If you have a purpose, then you will have direction in your life; not just simply existing. We all long for different things. What connects us is our appetite for a life that maximises pleasure and minimises pain.

Back in the day, this meant having shelter, access to water & food, and passing on our genes1. Today these are afterthoughts. Our hedonistic desires have been warped by modern life. “First world problems” as they are called. Today, people want six-figure salaries, never-ending supplies of credit, larger houses, finer cars, engaging friend circles, husbands that put the toilet seat down, career progression, and to be respected. They define themselves by careers, merits, level of education, the number of books on their shelves, how “liked” they are, or social followings. All different, but inevitably all the same. Happiness, fulfilment, and purpose. Although you may query the intrinsic value of some of these things in your own life, they are subjective. They also tend to be manufactured without our knowledge.

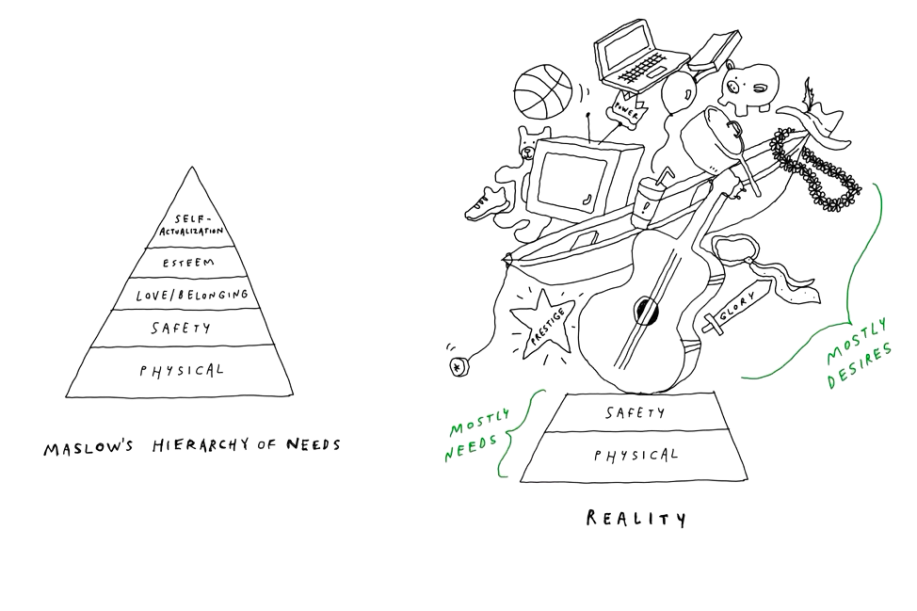

Luke Burgis, author of Wanting, would say we are spending less time in the world of needs and more time in the world of desires. We have a select few needs that are dictated by our physical basis for wanting. You don’t need external validation to know that when you are famished, you eat, and when you are dehydrated, you drink. Burgis believes that Maslow’s hierarchy is too “neat”. Following physical and safety needs, the remaining tiers are, in reality, a confused mess of desires.

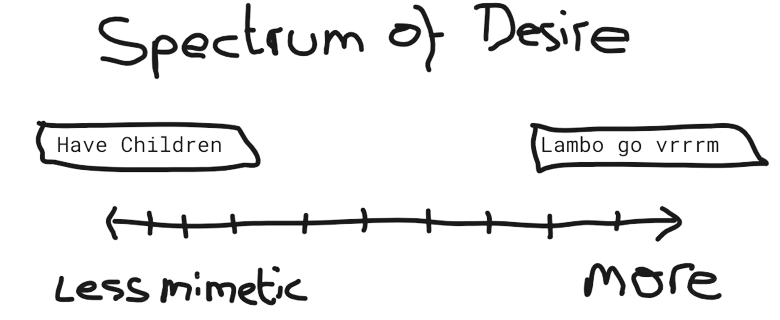

This alludes to the idea of mimetic desire that Burgis built upon2 ; that all of our desires are fructified through imitation. We want things because someone else does. The mediators of those desires range from friends, family, celebrities and historical figures. These desires exist within a spectrum; ranging from the innocent goal of starting a family to the exuberant display of wealth that is acquiring a Lamborghini.

These socially fortifying desires spread like wildfire; passing “from person to person like the energy between people at a concert or political rally”. The momentum creates a cycle, mutually reinforcing in nature, that can be either good or bad. It can lead to friendships or conflict. Burgis believes that humans “fight not because they are different, but because they are the same” and that it is their attempts to distinguish themselves that create disharmony. The troubling thing is that we are not aware of these subconscious levers.

“An unbelieved truth is often more dangerous than a lie. The lie in this case is the idea that I want things entirely on my own, uninfluenced by others, that I’m the sovereign king of deciding what is wantable and what is not. The truth is that my desires are derivative, mediated by others, and that I’m part of an ecology of desire that is bigger than I can fully understand. By embracing the lie of my independent desires, I deceive only myself. But by rejecting the truth, I deny the consequences that my desires have for other people and theirs for me.”

Luke Burgis, Wanting

There is an adage that women like their men to be taller than 6 feet. The idea has become so powerful that it’s embedded within the lexicon of meme culture. Part of this might be hereditary, but I suspect this is more so related to mimetic desire and the rise of social media & dating apps. Prospective mates have never undergone such levels of scrutiny, and the catalogue of potential partners has never been larger. Are we now so shallow as a species to intrinsically demand that our partners fit some pre-determined physical specification? Or is this mimetic theory at play?

We don’t, but the media does!

The majority of us are not aware of how mimetic desire works, but the bigwigs are; particularly those in the marketing department. Peter Theil hinted at this in his book, Zero to One, which contains many ideas from his former mentor René Girard, the founder of mimetic theory.

“Advertising doesn’t exist to make you buy a product right away; it exists to embed subtle impressions that will drive sales later. Anyone who can’t acknowledge its likely effect on himself is doubly deceived.”

Peter Thiel, Zero to One

Thiel talks about the inception of desire to that of the individual, but the objective of marketing is built around the idea of stimulating desire amongst a large group of people. That collective desire spins a flywheel; mutually reinforcing in nature. The very best marketers will understand mimetic desire, but can this effect be manufactured or is it simply a byproduct? Is it something we can only observe?

I think back to my days as a teen when parents would decide between the latest Xbox 360 or PS3 based on whatever the consensus amongst the peer group was.

“Oh, you all play Modern Warfare on 360? I’ll get that one too”.

Kids didn’t develop their console preference based on hardware specifications, they inherited it from their peers. While Microsoft can certainly be praised for its breakthrough Xbox 360 model3 that optimised for online play (the element which created network effects) there are industries centuries older than gaming that have long benefitted from mimetic desire. Such as the luxury industry where it is taken to the extreme. Unlike typical product-led companies, they induce demand whereby everyone wants it, but they won’t allow everyone to have it. My buddy Punch Card Investor wrote an excellent piece4 about LVMH and the luxury strategy. There he highlights the "anti-laws" of marketing luxury brands put forth by Kapferer and Bastien. Let's focus on just two.

In luxury, the role of advertising is to leverage mimetic desire to its fullest. Your mediators, those who are dripping in Gucci, Prada, and Versace, are incepting you. The authors of Luxury Strategy say that “brand is a transmitter of taste”. You believe your mediator has taste. You see some, you want some, you get some. So long as everybody continues to believe this, these brands will continue demonstrating Lindy5 properties. Luxury6 is one of the most fascinating studies of human behaviour there is. On the face of it, it makes no sense. When you understand the power of imitation, it does.

Chasing the next hit

Let’s get back on course. The problem with these first-world desires is that once you achieve them, they become less special, dwarfed by the scale of your next desire. You want a better job, so you work towards moving up the ladder. Perhaps you have to study to get there, and this is what motivates your education. You land the role, and now you want a six-figure salary. You get the salary, and perhaps your lifestyle has caught up with you. One hundred thousand dollars no longer feels special, so your new purpose is hitting some other artificial milestone. During this endless marathon, it helps to take a breath and appreciate how far you have come.

Sometimes I forget to appreciate how huge this newsletter is; I just see the numbers go up and they become meaningless. Only a few months ago I was celebrating the fact this community could almost breach Wimbledon Stadium’s capacity (that’s ~15,000 folks). Today, there would be another 5,000 people sitting outside, watching from Murray Mount. You have to purposefully stop and look back so that you can understand the gravity of what it is that you have done. But chasing purpose or ambition is not something I am picking fault with. In outlier cases, the persistent desire to achieve something greater has resulted in the most extraordinary innovators of our time. These people often sacrifice what most people would consider a “normal” life in pursuit of something far larger. Buffett is often celebrated as the workhorse of the investment industry, his head permanently buried in annual reports as he continues his lifelong consumption of corporate knowledge. Not often reported is the effect this has had on his acquaintances in life; like his late wife. Although the pair remained legally married and friends, she resorted to constructing an ‘open marriage’ with the oracle because of his distant state. She even introduced him to his second wife, Astrid Menks, who would move in with Buffett after his first wife’s passing.

Interestingly, there are many investors who borrow their sense of investing identity from Buffett. Rarely developing idiosyncratically, this prevents them from growing as an investor. I talk about that more here, but do these investors ever stop to ask themself “do I actually want to invest like this?”. It’s yet another example of our behaviours and wants being fabricated from the imitation of others. You might want to invest like Buffett, but I doubt many would like to live like him7. Even Buffett himself was an imitator early on; mimicking the style of his mentor Benjamin Graham. Later, he would adopt more influence from Phillip Fisher and his confidant Charlie Munger. My point is that most humans are not Buffett, and will chase these desires at the expense of paying attention to the present. In this way, life is just the mundane reality that exists between the now and the then. It’s a delicate balancing act.

A conversation between friends

I began thinking about all of this after witnessing an exchange about working environments in the finance sector with, let’s call them persons A, B and C.

Person A: Young people, GET INTO THE OFFICE. You are missing out on key relationship-building opportunities.

Person B: You must not have gotten the memo. We're optimizing for lifestyle now.

Person A: Ya. Tell that to your 60-year-old self.

Person B: I can promise you now I won't regret living a life focused on work flexibility, working on things that I care about, and building a strong family. Feel free me call me in 30 years.

Person A: You may be right. But the collective "you," interested in finance careers, is not right.

Person C: Correct. For better or worse those who aren’t in the office are looked down upon and thought of as lazy. If you want to be a worker bee, collect a paycheck and get stuck, fine. Work from home in this business. May the force be with you. But I suspect pit two against one another, the person going in every day will succeed. In a low-stakes career. Who cares. In a high stake where 7 figure salaries are available then that matters. And the upside is worth it.

There are merits in what persons A & C are saying. Person B also has great points. There is an upside to being a corporate slave if the payoff seems worth it. There is also no value that can be placed on having the freedom to spend your day as you choose and stay connected to your family. Do the two have to be mutually exclusive? What took place in that exchange was the clash of both ‘work to live’ and ‘live to work’ mentalities. Note the last point expressed by person C as they rationalise their argument by saying “the upside is worth it.” The upside being a seven-figure salary and the goods exchanged being your soul for some incalculable period of time. Extract emotional bias from the equation and persons A & C are right. Achieving that level of income, in that sector, requires some sacrifice (or nepotism). That is not to say this is how life ought to be lived. We are talking about working in an office (something that was an expectation until only a few years ago) vs working remotely. It’s trivial to most, but it highlights the conflicting subjectivity of happiness and purpose and how individuals weigh up these competing factors.

Persons A and C believe that happiness is a bargaining chip, to be leveraged for additional resources. Person B values these chips considerably more and doesn’t barter with them so carelessly. There is no right answer.

From Troy to Ithaca

In Homer’s the Odyssey, the island of Ithaca is Odysseus' home and where he is king. After the battle of Troy, he embarks upon a journey to be reunited with his wife and son which took ten years to conclude.

Homer’s poems breathe life into the myriad of adventures he endured along the way; two of the most famous being his encounters with the Polyphemus, the cyclops son of Poseidon, and the sirens of the sea that attempt to shipwreck Odysseus and his crew. This tale is a metaphor for the journey through life but also stands as a metaphor for all the desires and purposes that humans seek. The expectation of some reward in the future, to compensate for our actions in the present. Constantine Cavafy’s poem about the journey from Troy to Ithaca expressed it eloquently. He writes:

“Ithaka gave you the marvellous journey. Without her, you wouldn't have set out. She has nothing left to give you now. And if you find her poor, Ithaka won’t have fooled you. Wise as you will have become, so full of experience, you’ll have understood by then what these Ithakas mean”

Constantine Cavafy, Ithaca

Without the purpose of returning to Ithaca, Odysseus had no reason to experience these incredible adventures. When he reaches Ithaca the sense of purpose fades. But he has become wiser through his experiences. What use is getting from point A to B if you fail to appreciate the present in between? There will be hundreds of point Bs in a person’s lifetime. Waymarkers with the superficial appearance of being incrementally more important than the last one. Fail to stop and appreciate the path that you have carved, and your existence will be confined to that of a hamster wheel. We are all buried in the same dirt. As much as I agree that one should strive for a better quality of life, through whichever purpose gets them there, it would be a tragic conclusion to lay on your deathbed and regret not being more present as life whirred past you. There is a reason why someone with nothing can be exponentially happier than someone with everything. It’s perspective.

Every day is the same until it is not

There is a viscous bubble of social pressure that induces individuals to feel like they must always be doing something. Making headway on their life goals. You see others with purpose, and you want that too. This creates a perpetual feeling of restlessness. It is up to the individual to dictate the inflection point of their day. Compound this over months, years, or decades, and you might just achieve something incredible. But that doesn’t have to happen every day.

“Every day is the same until it is not”

My stupid ass

Here are two interpretations. On the one hand, it simply means that you are in control of dictating how each day plays out. Life will continue all around you but if you stand still yours will too. Compounding a bunch of days that are driven by purpose can have pleasing results. But it should also be said that one should not feel guilty for taking the time to do nothing. Not every waking moment of one’s life ought to be motivated by purpose. The other, perhaps darker, interpretation is that individuals sometimes allow life to pass by as though they sat on the fast-forward button. A continuous cycle of falling asleep on Friday to awake Monday morning. Passing through the motions. You may reflect on what you have done over the past month and realise you can’t remember. Nothing comes to mind. You are simply existing. I often wonder how an individual might manufacture the sense of perspective that others have. You will find that a large number of individuals who set up charities to increase awareness of knife crime, rape, cancer, and other tragic realities of life, have been, or have had family members be victims of these atrocities. The world forcibly thrusted this perspective into their lives and now they can't unsee it. It fabricates purpose to some extent. Regular citizens who are unplagued by these tragedies rarely give them a second thought. It’s not that they don’t care. It’s the privilege of not being endowed with the cocktail effect8. Our brains intentionally filter out things it deems not to be relevant to us, so that we may have clarity.

As it relates to investing, most of the significant learnings throughout an individual’s journey come from their own failures. Once you have experienced real dollar losses, the mistakes leave a lasting imprint. Once you have witnessed, first hand, the signs that a bubble was percolating it becomes easier to notice them the second time around. When you spend so much time amongst hundreds of investors you can more readily identify the bullshitters. But this all comes with one quite important caveat. Those who fail to learn from their mistakes are destined to repeat them. Perhaps it is just a reality of life that true long-lasting perspective comes only with experience.

Concluding with a return to the point of this memo. I do think there are ways to develop the perspective to understand how your emotions are stimulated by your own wants and desires. Whether you realise it or not, you are constantly searching for the next point B. This is fine, but it is important to acknowledge this self-induced social engineering and realise that having a destination is important but being present throughout it is what matters.

Thanks for reading,

Conor

I understand that, unfortunately, in some parts of the world that these desires are more visceral, less of an afterthought or an assumption. The direction I wanted to take this memo was in that of the first-world problems that more developed societies face. So excuse my lack of nuance going forward.

Originally developed by René Girard. Peter Thiel is also a known follower of the theory and shared many of the learnings in his book Zero to One. Luke’s book, Wanting, brought the idea back into the spotlight in 2021.

Which kicked off a real battle of the playground between the PlayStation consoles. Side note, the history of console wars, stretching back to the 1980s, is truly fascinating.

You can find that here. Credit to Punch Card Investor

From Lindsell Train: First articulated by Benoit Mandelbrot but popularised by Nassim Taleb, this is the observation that the longer something has endured, the longer it is likely to go on enduring. That the act of survival, itself is a demonstration of survivability.

Real luxury not items which are simply premium.

Maybe they do. Such is the power of mimetic desire.

Putting the toilet seat down is hard tho

Great write-up! One that I'm planning to read again later.