Something That Rhymes with QE

The Federal Reserve's Balance Sheet Decline Will End For Now

Having migrated to South Asia for the winter, I am now more than 10 hours ahead of the American timezone and more than 5 hours ahead of my home country. I find a lot of joy in being so disconnected from the time zones that usually govern my life1. I work for an American company, live in the United Kingdom, and largely invest across the United States and Europe.

In a professional capacity, it means I have the entire morning to myself. I still wake at 6:30am as usual, but now spend the first hour of my day sitting on a balcony sipping coffee and conversing as the sun rises. I then typically read for a while, exercise, and have several hours head start on the day to get some work done. The downside is that now the ‘busy’ portion of my day happens between 6pm and 11pm.

From an investment perspective, I have seldom been one to care much about time sensitivity. During earnings season, I often skim-read the announcements the day they occur and circle back for a closer examination days, sometimes weeks, later. Moreover, the market's open hours no longer coincide with the central part of my day. Thus, being a little more disconnected doesn’t hurt.

I woke up this morning to flick through the Federal Reserve December meeting (which occurred as I slept soundly). As I concluded, I couldn’t help but feel a regime shift is underway.

From QE to QT

In Q1 2020, at the outset of the pandemic, the Federal Reserve reacted quickly by lowering borrowing costs and stimulating an economy that risked grinding to a halt. The rate was promptly slashed 50bps from 1.75% to 1.25% in early March. Just weeks later, the rate was cut by 100bps to 0.25%, where it would remain until February 2022. Coinciding with this decline in borrowing costs was a monumental bout of quantitative easing (QE). The Reserve pulled out its cash bazooka and started buying.

From March 2020 to its peak in April 2022, the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet swelled to more than double its size, growing from $4.1 trillion to just shy of $9 trillion. The situation was so bizarre that in 2020, the Reserve used a legal workaround to purchase corporate bond ETFs. Between the 12th May and 17th June, some $6.8 billion was used to purchase a mixture of investment-grade and high-yield (aka, Junk) bond ETFs.

As the panic subsided, life gradually became ‘normal’ again, and markets settled. The Fed would put an end to the QE cycle in March 2022 by conducting a 25bps rate hike and ceasing to be a net purchaser of assets. It was now time for quantitative tightening (QT). Thanks to an unwelcome side effect of explosive stimulus and a recovery boom in consumption, inflation started to infect the economy. In retaliation, rates would climb at a fast clip, climaxing at 5.50% in 2023, and the balance sheet would become $2.4 trillion lighter (27% down from peak).

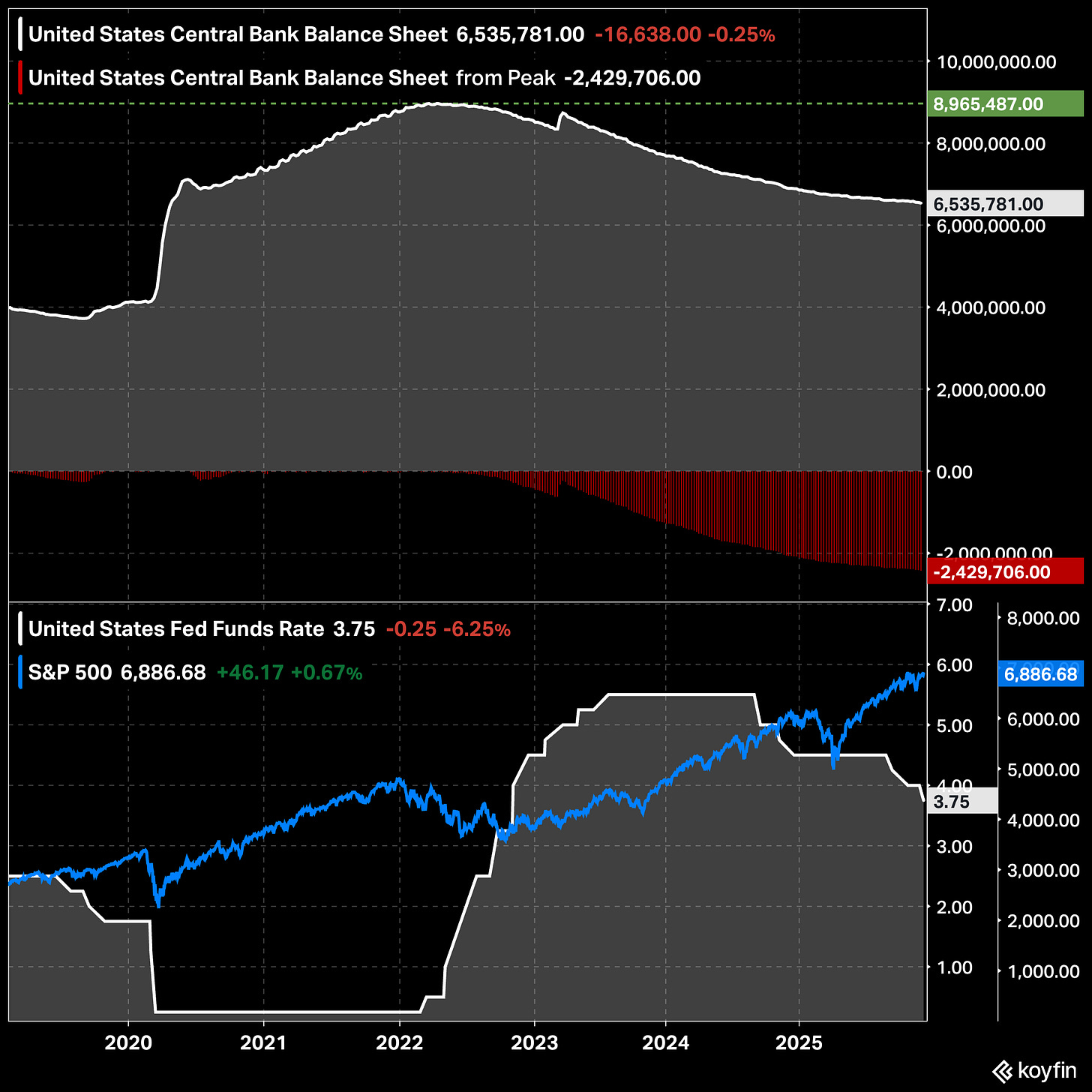

Examine the chart below, which displays the Federal Reserve balance sheet, the level of the S&P 500, and the Federal Funds Rate since 2020. You can bear witness to the striking correlation between the Fed’s actions and the S&P 500.

The onset of the pandemic saw the S&P 500 tumble more than 30% in the space of a month. Precisely at the time the Fed unholstered its arsenal of financial weapons, the index, seemingly unperturbed about the state of the world, climbed out of the trough and aggressively marched forward. By August 2020, the 30% drop in March was erased. The fastest retracement in history. A recovery that had far more to do with liquidity than fundamentals.

By December 2021, the S&P 500 was up 120% from its lows and ~45% above its level before the pandemic started. Then the Fed began to indicate that it was time for rates to climb again in 2022. The market drifted downwards over most of 2022 as the Fed’s signalling became reality, falling 25% from highs as rates surpassed 3%.

To this day, there are industries still feeling the hangover of the turbulence in supply and demand dynamics from the pandemic. Yet, by 2024, the economic situation looked relatively stable once again. Inflation, which peaked at 9.10% in June 2022, was back in the 3% range. Unemployment had gradually declined from the pandemic highs of 14.70% in 2020 and was now oscillating around the mid 3% range. Corporate earnings had turned a corner, and the semiconductor and AI narrative had begun to sweep across markets, concocting Wall Street’s latest distraction. After declining by 18% in 2022, the S&P 500 recorded annual returns of 26% and 25% in 2023 and 2024, respectively. By the time that President Donald Trump reminded markets of his recurring tariff fetish in February 2025, it was as though the pandemic was long forgotten. There was a new panic in town.

Something That Rhymes with QE

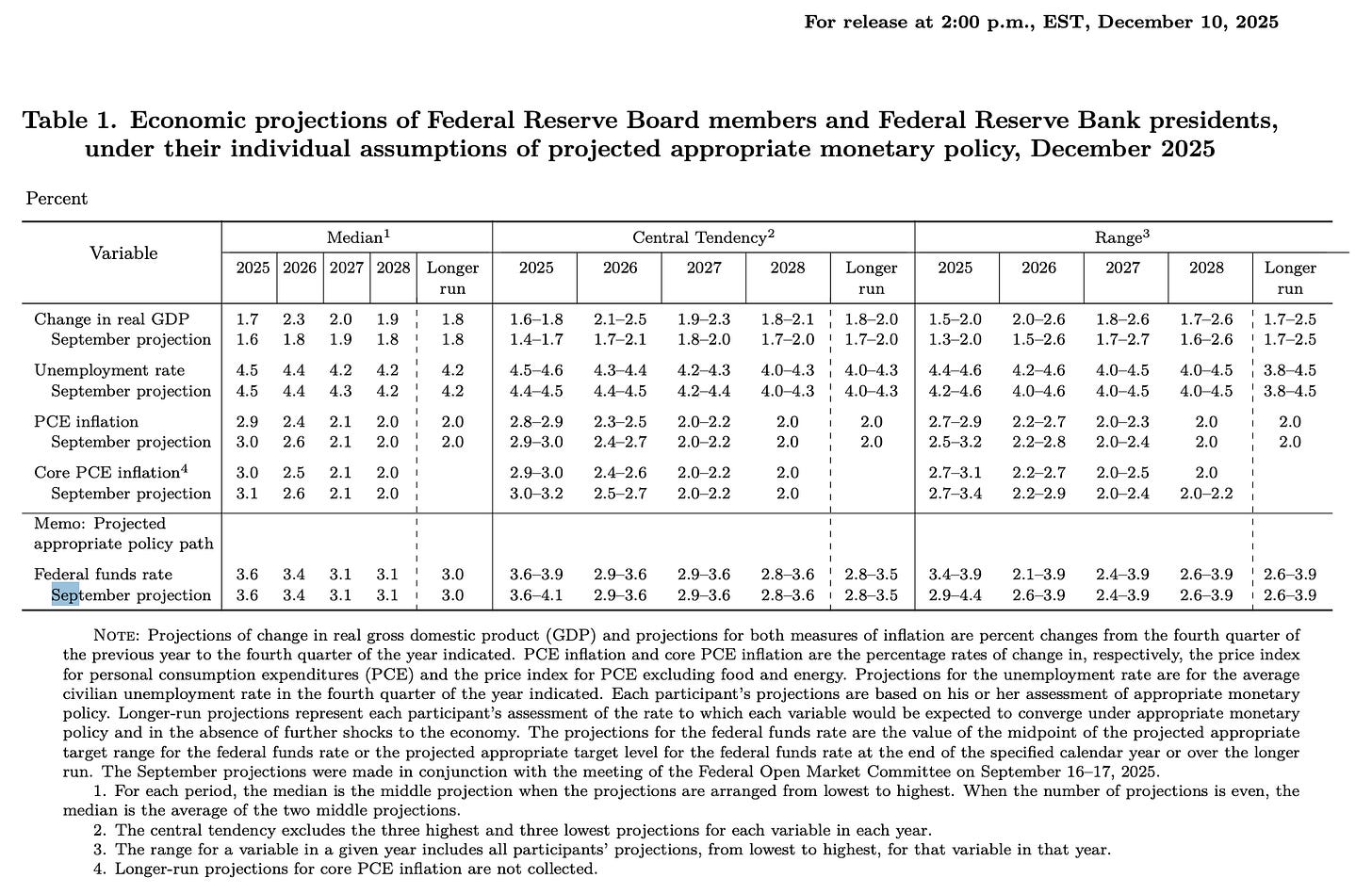

Fast forward to December 2025. Rates had been declining for well over a year as the Fed continued to reduce the size of its balance sheet. Just last night, on December 10th, the Reserve announced a further 25bps cut, taking the rate to 3.75%. Within the press release, the Summary of Economic Projections (SEP)2 depicts more modest rate cuts going forward with a median of 3.4% in 2026, 3.1% by 2027, and 3.0% in 2028. But notably, they did not commit to further cuts, stating they will “carefully assess incoming data”.

More interestingly, the statement remarked “The Committee judges that reserve balances have declined to ample levels and will initiate purchases of shorter-term Treasury securities as needed to maintain an ample supply of reserves on an ongoing basis”.

This translates to the Fed saying that the balance sheet is unlikely to shrink in the near term. The agenda of QT appears to be concluded for this cycle. While the intention to resume purchases of shorter-term treasuries nods to the easing of financial conditions, it’s not quite easing in the quantitative sense. It’s not a shift from shrinking to growing the balance sheet. It’s a shift from shrinking to maintaining the balance sheet. Stabilisation, not stimulus.

This may give the Reserve some time to assess what the economy needs. In the release, they alluded to persistent uncertainty about the near-term outlook.

“Available indicators suggest that economic activity has been expanding at a moderate pace. Job gains have slowed this year, and the unemployment rate has edged up through September. More recent indicators are consistent with these developments. Inflation has moved up since earlier in the year and remains somewhat elevated. Uncertainty about the economic outlook remains elevated”.

It’s not unreasonable to assume that the Reserve will resume QE should the economy deteriorate further.

First QT slows

Then QT stops

Next, purchasing short-term treasuries to stabilise

Perhaps a few more rate cuts to follow

Economy worsens ➝ Resume QE

But what if the economy somehow improves?

I can confidently attest to having no idea. I don’t have data that stretches back far enough. Nor do I have the first-hand experience. I was raised in a post-GFC era, where the rules changed forever.

The same dynamic between the central bank balance sheet and interest rates was not present during the GFC. From 2007 into early 2008, the Fed gradually expanded its balance sheet while cutting rates to practically nothing. Then, when the financial system collapsed in late 2008, the balance sheet went vertical, more than doubling within months. There were small bouts of balance sheet reduction in 2010, 2011, and 2012 that coincided with declines in the S&P 500, but rates remained fixed at 0.25% for half of that decade.

The next time the Fed downsized was at the end of 2017, while rates gradually increased to 2.5% by the summer of 2019. By August of that year, the Reserve began to ease. Assets climbed 10% by February 2020 in response to the repo crisis. Meanwhile, rates had fallen to 1.75%.

You could argue a resemblance to today in this period. The QT slows and stops by 2019. A few rate cuts come, QE resumes. But then an anomaly arrived (the pandemic), and we never got to see how this would have played out because the Reserve had to react to a different fire.

New Chapter

The Fed has signalled it will stop reducing its balance sheet, but this doesn’t mean that QE is upon us. I’ve witnessed a lot of commentary indicating that we are not far away from a repeat of the 2020 QE cycle, and this will be a huge boon to stocks. While I have learned to never say never in the stock market, I am confident that if this were to happen, it would not do so on the same scale. Moreover, I can’t help thinking that this is an act of recency bias.

I am more comfortable acknowledging I have no idea what will unfold in the near term, but that we are now entering a new chapter in financial history. For all the analogies I could muster, we are still living in a monetary regime without a great deal of precedent.

Thanks for reading,

Conor

Great coverage with depth yet in a succinct manner. Koyfin charts always great.

Thank you!