Slowing Down

Why novelty improves our perception of time

Time Flies

The saying goes; time flies when you’re having fun. But what if it doesn’t? I have the most fun when I try new things, and find that when I experience newness, time slows down. They also say time goes by faster as you age. We tend to measure time by recounting significant events in our life and fewer of those happen as we grow older. Our first day at high school, our first beer, our first job, the first time we fell in love. The road to adulthood seems to last considerably longer in our memories; as though time was patiently waiting for us to grow up. When we mature, it no longer affords us that privilege. The human brain is indescribably brilliant. But human progress has evolved so rapidly, and the daily stimulation we are subject to has compounded so significantly, that our primitive brains are playing catch-up in an increasingly complex world.

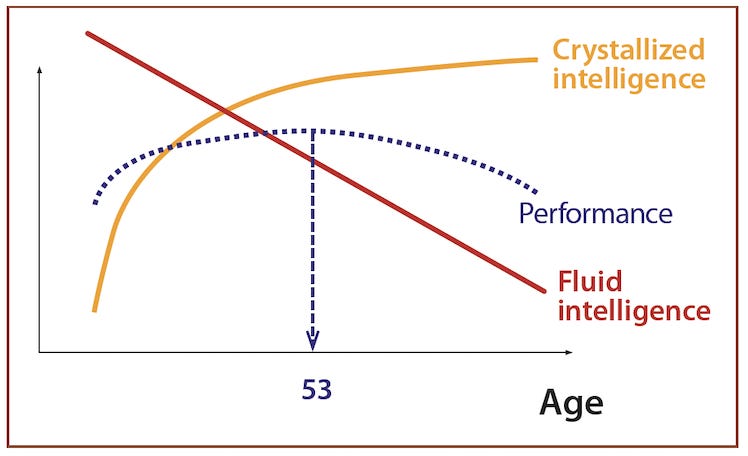

It’s no secret that our cognitive dexterities degrade with time. A wise couple once told1 me that like taxes, there’s no avoiding it. Early in life, we have an abundance of fluid intelligence; our ability to solve problems in novel ways. This is what helps us learn new things, grasp complex concepts and engage in abstract thinking.

As life progresses, we build an ever-expanding base of knowledge and form crystallised intelligence; our ability to solve familiar problems because of our accumulated knowledge and life experience. These two variables are countervailing trends, and this fact is one of the difficult realities of ageing.

“The most important thing as an individual ages is to start to simplify things. Because as we age, we lose the flexibility in our brains to make complex decisions, especially if we need to make them quickly”.

Dr Carolyn McClanahan

As our understanding of the world develops, most of the things we do are no longer novel. The way we perceive time is affected by how much new information our brains are processing. When we are young, the world is full of new things to learn and experience, so time seems to pass slowly. As we get older, we become more familiar with the world around us, and time seems to pass more quickly. This is commonly enhanced by the fact that some people actively avoid stimulation that is outwith their comfort zones later in life. I’m sure it comes as no surprise that the same effect materialises in your working life. When you start a job, it’s usually exciting for the first few months; maybe even a year. When you settle into a routine, weeks fly by faster because you are acting under the command of the subconscious. If you are fortunate enough, you will never get bored with your job. If you are more fortunate still; you will dictate how, and when, you work.

“Most people, deep down, want to be wealthy. They want freedom and flexibility, which is what financial assets not yet spent can give you. But it is so ingrained in us that to have money is to spend money that we don’t get to see the restraint it takes to actually be wealthy”.

Morgan Housel

But for most people, that isn’t true. Life will whir past us when we get embedded into a routine. Weekends will become shorter and Monday will knock at your door earlier after clocking off each Friday. In the age of multitasking, the act of doing multiple things at once ignites the passing of time as though it were drenched in gasoline. There is evidence to say that the productivity benefits of multitasking are a myth. Instead of focussing on a single task, you instead give partial focus to a myriad of tasks. You are not multitasking, you are simply switching between tasks in quick succession. This hinders productivity, but it also affects our perception of the passing of time. A 2015 study2 showed that participants who watched TV commercials while performing mundane tasks felt that time passed faster than those who just watched the commercials.

We need to stop consciously multitasking. This mixes up the energy waves in the brain and creates a sort of tsunami energy effect in the brain and mind and body which will distort our perception of time”.

Carloline Leaf, neuroscientist

In the modern day, we are all but forced to multitask, so avoiding it can be difficult. The solution, according to neuroscientist, David Eagleman, is to “seek novelty”. He claims this works because “new experiences cause the brain to write down more memory, and then when you read that back out retrospectively, the event seems to have lasted longer”. We’ll come back to David shortly.

Seeking Novelty

Last weekend, I attended a birthday party that initiated this train of thought. I was reconnecting with a few old faces (and a few new ones) during my current trip to India. At one point, I was engaged in conversation about a mutual love of travel and someone said something along the lines of “when you travel, time slows down”. I was in complete agreement. Time does pass by slower when you are travelling. A five-day trip to Paris might feel like two weeks back home. In our new environment, we are more perceptive. We stare at buses longer because they are coloured differently. We pay more attention to restaurants we pass because we don’t know where’s good to eat yet. We spend longer in grocery stores because we are interested in what they have that we don’t. And we explore areas of the city that residents take for granted. Everything is new, and instead of stomping on familiar grounds, we are free from routine and the crystalised understanding of our surroundings. We take time to soak things in and notice more details. We are present.

Side note: It can expensive to travel but life can get boring staying in the same city. You’d be surprised at how fun adopting a ‘tourist’ mindset to your own city can be.

Being present is the new aspiration of the 21st century. Whether it’s taking time to appreciate the finer details of the objects around you, or truly absorbing a conversation you are having, the goal is to appreciate and have a visceral connection to the gap between points A and B.

“What use is getting from point A to B if you fail to appreciate the present in between? There will be hundreds of point Bs in a person’s lifetime. Waymarkers with the superficial appearance of being incrementally more important than the last one. Fail to stop and appreciate the path that you have carved, and your existence will be confined to that of a hamster wheel”.

There are studies3 that suggest practitioners of meditation, a form of mindfulness, performed more accurately in psychophysical time perception tasks. There are also analyses of brain plasticity4 that imply constantly prompting your ageing brain with new stimuli can improve mental capacity and counteract the signs of Alzheimer's disease. Here I think about people like Iris Apfel (101), Warren Buffett (92), and Charlie Munger (99) who are still thriving in their respective fields despite their ages.

Everyone has this belief that as we age we ought to slow down. Do less. Think less. Take it easy. Retire. But what if those things accelerate the process of ageing?

At 96, Apfel, a fashion legend, was asked what keeps her going and she reasoned that "thinking young" and having a sense of wonder, as well as communicating with younger generations, is what helps her stay sharp.

“When you get older, as I often paraphrase an old family friend, if you have two of anything, chances are one of them is going to hurt when you get up in the morning. But you have to get up and move beyond the pain. If you want to stay young, you have to think young.

Having a sense of wonder, a sense of humour, and a sense of curiosity — these are my tonic. They keep you young, childlike, open to new people and things, ready for another adventure. I never want to be an old fuddy-duddy; I hold the self-proclaimed record for being the World’s Oldest Living Teenager and I intend to keep it that way.”

I am fortunate to have two grandfathers, both of a similar age. Yet, one retired in their late 50s and the other only recently gave up their profession after approaching their mid-70s. The two could not be any further apart, mentally and physically.

This exploration of time perception was sparked by my appreciation for travel. Through great fortune, I now have the privilege of spending several months of the year in India; a place that couldn’t be any more different from the UK. When I arrive, it shakes up my entire routine and time passes by slower. This is mostly down to luck, however, and travelling can be expensive. As I am reminded that time can move slower (perceptually, at least) I am also reminded that there are other ways we can feel more present outside of hopping on a plane. Let’s revisit Eaglemen.

How nearly dying makes time slow down

Neuroscientist, David Eaglemen, has spent most of his life passionately researching topics like brain plasticity, sensory substitution, and time perception. He refers5 to time as “this rubbery thing" that “stretches out when you really turn your brain resources on” and “shrinks up when you say, ‘Oh, I got this, everything is as expected”. He has ways of demonstrating this effect in motion. When Eaglemen was a young boy, he and his brother used their imaginations to transform a housing construction site into a playground.

After mistakenly falling through what he perceived to be a stiff panel on the roof of a house (but was, in fact, a tar paper covering) he descended into the living room of the unfinished project and remembers thinking “this must be how Alice felt when she was tumbling down the rabbit hole”. He recalls the intricate details of his decline; “the brick floor floats upward, some shiny nails are scattered across it, as [my] body rotates weightlessly above the ground”. He felt as though his brain was in a hyper state; processing his surroundings much faster than usual. Later in life, David would recreate near-death experiences to measure an individual’s perception of time. He would ask subjects to partake in an experiment using a scad; an apparatus which closely resembles a theme park ride. Scad is short for suspended catch-air device and looks something like what you see below. It's quite similar to bungee jumping. The exception being there is no bungee.

“A steel gondola hung between its four legs and could be lifted to the top by thick cables. When the rider reached the top of the tower, he’d be hooked to a cable and lowered through a hole in the floor of the gondola. His back would be to the ground, his eyes looking straight up. When the cable was released, he would plummet a hundred and ten feet, in pure free fall, until a net caught him near the bottom”.

Eaglemen would ask the subjects to wear a small device, called a perceptual chronometer, on their wrist that would flash numbers on the screen at a rate that was difficult to read to those on the ground. He reasoned that the subjects would be able to read the numbers during their fall if their brains were truly in a hyper-sensory state. This hypothesis turned out to be a dead-end, the numbers were still illegible, but something far more interesting fructified from his experiment. His subjects would overestimate the length of their fall by 36% on average. They reported the same slow-motion effect that David had while falling through the roof as a child.

“Turns out, when you're falling you don't actually see in slow motion. In some sense, that’s more interesting than what we thought was going on. It suggests that time and memory are so tightly intertwined that they may be impossible to tease apart”.

Time slowed down for David at that moment on the construction site, and because it was such a horrific experience6 it remained lodged in his memory for years to come. His findings from the scad made David realise that it had nothing to do with a heightened sense of perception; it was about memory.

“Normally, our memories are like sieves. We're not writing down most of what's passing through our system. Think about walking down a crowded street: You see a lot of faces, street signs, all kinds of stimuli. Most of this, though, never becomes a part of your memory. But if a car suddenly swerves and heads straight for you, your memory shifts gears. Now it's writing down everything, every cloud, every piece of dirt, every little fleeting thought, anything that might be useful. In a crisis situation, you're getting a peek into all the pictures and smells and thoughts that usually just pass through your brain and float away, forgotten forever”.

The takeaway here is not to physically slow down. Rather, optimise the moments you do work towards being in a flow state; not burdened by the act of multitasking. But more so, a reminder to appreciate that we can slow down the perception of time by seeking out new experiences and learning new things. This can help to keep our brains active and engaged, and it can also make life more enjoyable. Or as Paul Graham7 put it:

"Relentlessly prune bullshit, don't wait to do things that matter, and savour the time you have. That's what you do when life is short”.

Thanks for reading,

Conor

Time perception, mindfulness and attentional capacities in transcendental meditators and matched controls (here). It’s worth noting, the results are not conclusive.

Defined as the ability of the nervous system to change its activity in response to intrinsic or extrinsic stimuli by reorganizing its structure, functions, or connections. It’s said that plasticity is stronger in young brains as we learn to map our surroundings using the senses. As we grow older, plasticity decreases to stabilize what we have already learned.

His nose cartilage was so badly smashed that an emergency-room surgeon had to remove it all and replace it with a “rubbery proboscis that he could bend in any direction”.

To which I reply, Conor, with another person's words. You might be in the rara avis cohort of the financial world to appreciate the poem I share below.

Why Fool Around?

Stephen Dobyns

How smart is smart? thinks Heart. Is smart

what's in the brain or the size of the container?

What do I know about what I do not know?

Such thoughts soon send Heart back to school.

Metaphysics, biophysics, economics, and history-

Heart takes them all. His back develops a crick

from lugging fifty books. He stays in the library

till it shuts down at night. The purpose of life,

says a prof, is to expand your horizons. Another says

it's to shrink existence to manageable proportions.

In astronomy, Heart studies spots through a telescope.

In biology, he sees the same spots with a microscope.

Heart absorbs so much that his brain aches. No

ski weekends for him, no joining the bridge club.

Ideas are nuts to be cracked open, Heart thinks.

History's the story of snatch and grab, says a prof.

The record of mankind, says another, is a striving

for the light. But Heart is beginning to catch on:

If knowledge is noise to which meaning is given,

then the words used to label sundry facts are like

horns honking before a collision: more forewarning

than explanation. Then what meaning, asks Heart,

can be given to meaning? Life's a pearl, says a prof.

It's a grizzly bear, says another. Heart's conclusion

is that to define the world decreases its dimensions

while to name a thing creates a sense of possession.

Heart admires their intention but why fool around?

He picks up a pebble and states: The world is like

this rock. He puts it in his pocket for safe keeping.

Having settled at last the nature of learning, Heart

goes fishing. He leans back against an oak. The sun

toasts his feet. Heart feels the pebble in his pocket.

Its touch is like the comfort of money in the bank.

There are big ones to be caught, big ones to be eaten.

In morning light, trout swim within the tree's shadow.

Smart or stupid they circle the hook: their education.

Great article Conor.