Return is the ONLY Measure of Success

Thoughts on return being the ultimate measure of success for an investor

“Return, specifically the surplus generated relative to a chosen benchmark, is the ONLY barometer of success for an investor”.

Concentration Pays

That’s a polarising statement, isn’t it?

A few weeks ago, I stumbled upon a tweet from Mr Arny Trezzi, which has garnered 250,000 impressions (and counting). He pointed to his 403% return compared to the S&P 500’s 29% with an undercurrent of irony towards the fact he was unable to get a job at a hedge fund— it’s likely this performance decemates most hedge funds over this period. Naturally, I dove into the comments. To my delight, the comments were overwhelmingly positive (I was expecting a few “aCktUaLlLyY” reply-guys).

This tweet intrigued me, but I think some context is important to lay the groundwork for what I want to discuss. Paraphrasing Arny for a moment, this return was generated:

From a start date of August 2023.

Without leverage or options.

By carefully picking individual stocks.

Via considerable concentration (having been 100% long Palantir (PLTR) several times and for most of the period.

Without the intention of selling courses or advice.

Without regard for ‘traditional’ measures like Sharpe ratios, et al.

With the acknowledgment that money managers can’t invest in this fashion.

For a longer breakdown, I implore you to read it straight from the horse’s mouth— here

I’ve spoken to Arny a couple of times over the years and am genuinely thrilled to see the success of his input. My perception of him is that he is bright, works incredibly hard, and doesn’t take himself too seriously. I think it’s evident that while he may appear to be exclusively focussed on a very limited number of stocks (one or two most of the time), he is a workhorse and loves what he does. Ultimately, an investor’s lessons are theirs to learn. One shouldn’t find oneself becoming too invested in the triumphs and failures of others. As Ralph Waldo Emerson once wrote, "Envy is the tax which all distinction must pay”.

I say this to preface that I am going to discuss other perspectives, and these perspectives are not necessarily my own, nor are they exclusively aimed at Arny’s situation. Rather, a broader discussion on returns, how someone might generate those returns, and our tendency to engage in comparison.

The cat who touched the stove

A perfectly natural exhibition of cynicism (or ‘realism’, depending on the stroke of your brush) would be to state, “Cool, try do that again”. The performance period spans less than two years, after all.

For every individual who made a killing shoving the stack into a stock at the right time, there are 99 who went all-in with the losing hand. Arny’s style is high-risk, high-reward, and it doesn’t require much imagination to conjure up arguments against his philosophy. By all means, single stock portfolios are less an impressive display of skill and more so an exhibition of courage, cojones and fortunate timing.

There is a parable about a cat that sat on a stove top. It goes something like this.

“A cat that sits on a hot stove will never sit on a hot stove again... but it will also never sit on a cold one”.

By my math, Arny’s CAGR at the time of the tweet was ~165%. Suppose he sold everything, allocated 100% to cash, and did nothing for a decade1. The CAGR would be 17% (before inflation)— a 700 bps surplus to the lifetime CAGR (10%) of the SPDR S&P 500 ETF, SPY.

But the cat that never sat on a hot stove before will continue sitting on the stove, assuming it will be cold, until the day it is not.

Not all trends are built the same

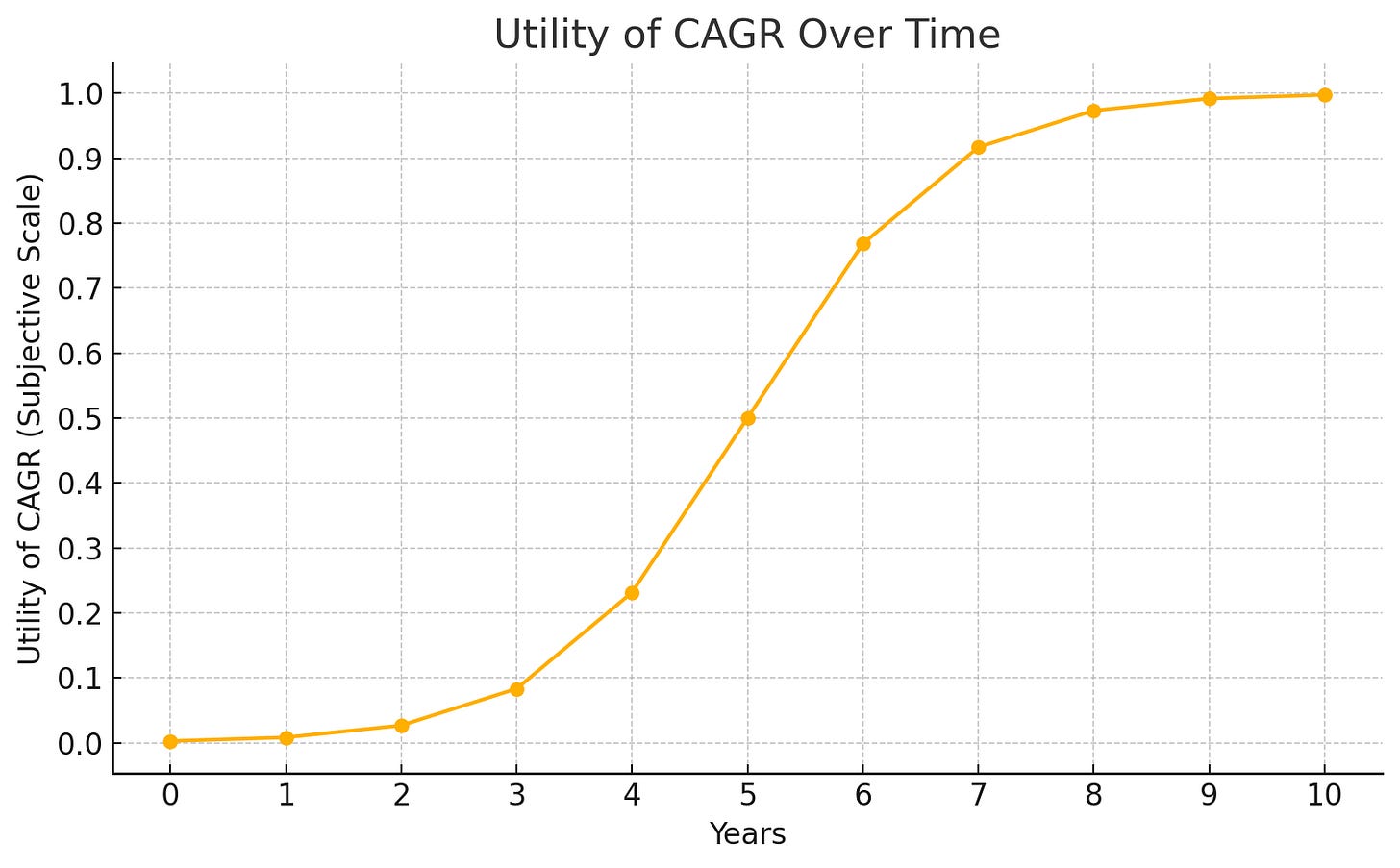

In the analysis of trends, I distinguish between fads (a moment), trends (a movement), and sustainable trends (trends with a second act). Concerning performance, you can think about it this way. A great short-term performance (say 0-2 years) is a fad— likely the result of luck or dominant market narratives or themes. You own a lot of energy stocks, which are in favour, and your portfolio does well.

A solid medium to longer-term performance (say 3-10 years) is a trend. Within this period, there is likely to be one or two cycles that have passed— with various factors and themes having their moment in the sun. Luck is less of an influence. If you come out the other side with a solid performance, then it’s more likely you have not simply got lucky playing the same hand repeatedly. There is an element of skill that has resulted in this return— whether that be in allocation, rebalancing, patience, opportunistic transactions, etc.

A strong long-term performance (10+ years) is a sustainable trend— although I dislike calling anything about investing sustainable because a lapse in judgement can come at any time. The idea here is that most investors with an aptitude can ride a bull market for a decade— a tide that lifts all boats. But it takes serious metal to endure several cycles, multiple bear-bull rotations, recessions, etc. The ‘second-act’ here refers to genuine skill and ability to generate excess returns during alternate regimes.

Compounded annual growth rates (CAGRs) are an incredibly effective way to measure and compare growth rates, but their utility is weak in the short term. Consider a start-up that generates $500,000 in sales in January. Someone then annualizes it to suggest they make $6 million this year. But if January was plumped-up by a one-time contract, the projection is misleading. Now, consider the S&P 500 did 10% in returns by January. Annualized, that’s well over 110%!

News flash: the index has never surpassed a 50% return in a calendar year. In stand-alone calendar years, it can be dangerous to place too heavy an importance on the S&P’s return. At the time of writing, the S&P 500 has returned 5.2% in the last year. Over the past 2 years, that’s 15.7%— 7.6% in 3 years, 8.4% in 4 years, 15.6% in 5 years, and so on. As the period observed gets longer, it gravitates towards the long-term average (10.04% over the lifetime of the SPY ETF).

An investor who earns a 15% return in a calendar year is not impressive. Nor is, in my opinion, an investor who earns a 150% return in a calendar year. A chimpanzee could do the same. Nonetheless, I bet it feels incredible (I wouldn’t know).

In 2024, in a piece called ‘Fads and Second Acts, ’ I wrote about the difference between short-term fads, longer-term trends, and sustainable trends. I’ll save you the reading and just share the conclusion.

“It’s important not to dismiss every trend as a fad. It’s equally important not to confuse every fad as a sustainable trend through extrapolation. It’s considerably more important to — take the time to ponder the difference between the two; identifying to the best of your ability which you may have stumbled across”.

This is all to say that we shouldn’t judge investors too harshly or praise them too heavily over short-term periods. That goes for shaunfreunde (revelling in the misery of others) and hubris (exaggerated pride or self-confidence in one’s abilities), too.

Hedge funds don’t work that way!

One commenter on Arny’s thread said the following:

“Hedge funds are about managing risk hence why it’s called hedge fund. What’s your sharpe and sortino ratios? What’s your max drawdown? What’s your factor risk exposure? What’s your idiosyncratic portfolio alpha vs. Systematic return?”.

Where to start….

I have a sense of appreciation for the response in some ways. It’s a common trope to question why money managers and/or financial advisors exist when “you can just buy the S&P 500 and pay no fees”. This sentiment misses the point entirely.

I think it’s a blessing to have such an interest in finance, money, and markets that you are willing to put your capital behind your ideas— to read the filings, read the transcripts, follow the footnotes, and what have you.

In reality, there is a tiny pool of people with a personality suited to this type of dedication. For many, whether it be a lack of time, interest, risk appetite, or education, offloading that burden to someone else— to use an advisor as an example— is a godsend. Advisors are not stock pickers by trade, but they help bring balance and structure to your finances through allocating funds, understanding your goals, tax planning, retirement planning, budgeting, cash flow planning, rebalancing, insurance, and a host of other services.

In short, an advisor’s fee is not a derivative of their ability to outperform the market. Nor is a hedge fund’s sole purpose to have the best performance known to man. They are certainly more geared towards outperformance than an advisor, and they are not merely tracking a benchmark like a mutual fund or an index fund, but they can provide access to more exotic instruments and generally have greater flexibility concerning how they invest.

What’s your sharpe and sortino ratios? What’s your max drawdown? What’s your factor risk exposure? What’s your idiosyncratic portfolio alpha vs. Systematic return?”.

To repeat the above comment once more highlights the bliss of being an individual. None of that shit really matters to an individual. Individuals cannot be compared to institutions.

Is Return the ONLY Measure of Success?

Circling back to the question that was provoked by Arny’s tweet. Is return the only measure of success?

It depends on who’s asking.

If you ask the populants of the world today “is the world getting better or worse?”, an incredible number of people will tell you the world is a worse place today than it was 30 years ago. In my opinion, these people are either morons or suffering from a tragic level of ignorance. As much as the media tries to persuade us otherwise, there has never been a greater time to be alive than today— this is factually correct when assessing the conclusion across most variables.

The percentage of the global population living in extreme poverty today is 8.5% compared to 29% in 19952.

The global female literacy rate has increased from 70% in 1995 to 84.1% in 2023.

The global infant mortality rate has declined from 59.4 deaths per 1,000 children (5.94%) to 27.3 (2.73%) since 19953.

The global life expectancy is now 73 years, up from 64 years in 1990.

In 1995, just 1% of the population had internet access; today, it’s closer to 70%.

Global hunger rates, access to electricity and safe drinking water, aviation fatalities, child vaccinations, child labour… the list goes on. There are so many signs the world is a better place today.

Yet, with all that said, I can still understand why some people feel the world is not a better place. Most often, they base their assessment on some niche perspective that, within the context, justifies the answer of “no” to the question I proposed. The laws of mimesis show that humans tend to compare themselves to those closest to us. It’s why notions such as “relative poverty” exist and are legitimate.

In a similar vein, if you ask investors, “Is return the only measure of success?” there is an accurate and holistic answer. I believe that for the most part, the most accurate and convincing answer is “yes” if we change the word ‘only’ with the term ‘most important’— “Is return the most important measure of success?”.

Ultimately, investing is about taking your idle dollars and putting them to work in the hopes that they deliver returns. But returns relative to what? The question is open-ended. This is where the answer is not so straightforward.

In excess of inflation: Every year, idle cash loses value thanks to inflation and currency devaluation. In other words, $100 today will purchase considerably less than $100 in 20 years.

In excess of the ‘Market’: The ‘market’ is different things to different people. To some, it’s the MSCI World. To others, it’s the S&P 500. Whatever the case, if you could have earned more money, doing effectively nothing more than buying a passive ETF that tracks ‘the market’ then some will say your time has been wasted.

In excess of the ‘Benchmark’: Some of you might say, “What is the difference between a benchmark and the market?”. We could argue semantics, but everyone’s version of ‘the market’ is a benchmark, but not every benchmark is someone’s version of ‘the market’.

In excess of Everyone Else: To be ‘the best’ investor there ever was. A fine goal, as unrealistic as it may be.

Everyone has their version of what their returns are measured against. Whatever that is, the relative returns should be the most important measurement of success. If you are dedicating precious time towards this pursuit, then you should be validating whether that time was well spent. I think I have written about this extensively in the past, so I will spare the detour.

However, I think there is huge success in simply having the awareness to appreciate the potential life-enhancing force that investing can be, while at the same time demonstrating the respect and understanding that it’s not ‘free money’.

In a similar way that the Western world seldom appreciates the fact they have an abundance of clean drinking water, a ‘sophisticaed’ investor infrequently appreciates the fact they are already ahead of most of the population by having the wherewithal to prioritise their financial health.

From the perspective of a UK resident, the level of education and enthusiasm surrounding public markets are abysmal. The Office for National Statistics (ONS) reports that in the 2022/23 tax year, there were 12.4 million ISA accounts subscribed to in a country of ~45 million adults. An Individual Savings Account (ISA) is a tax-shielded investment wrapper that allows UK residents to invest up to £20,000 (~$26,000) per tax year, with all resulting capital gains and dividends exempt from tax, forever.

Of the 12.4 million accounts, 64% (7.9 million) were cash ISAs— an account that simply lets an individual earn tax-free interest on cash. Considering the UK has averaged 1.96% interest rates over the past 20 years, these individuals would have likely failed to circumvent inflation. Just 31% (3.8 million) of accounts were Stocks & Shares ISAs— an account that facilitates the purchasing of equities, ETFs, and funds protected from tax. In theory, a UK resident could max their stocks ISA each year and become a millionaire within 25 years, assuming a 7% annual return, and pay zero tax on that portfolio.

I’ll hazard a guess that 90% of my readers view the decision between utilizing the £20,000 annual allowance towards a stocks ISA and a cash ISA as a no-brainer. Yet, for most Britons, this isn’t the case.

It’s widely reported that more than 50% of American households own stocks directly. While harder to find a perfect comparative data set for the UK, the best estimate is between 20% to 25% for UK households. I therefore think it’s an incredible success for someone in the UK to get over their cultural risk adversity and real-estate-fetish and allocate money towards a stocks and shares ISA product.

As you become more competent in investing, naturally, you delve into alternate universes of comparison. We tend not to compare ourselves to people we consider ‘below’ us. Rather, those who are on roughly the same ‘level’ or slightly above us. When comparing your salary, you often look at people in similar job functions, of a similar age, and in the same country to gauge how fairly you are compensated.

Most new investors are not fixated on beating the S&P 500— they are more content with tracking the percentage of income they invest and learning how to invest. As time progresses, your base for comparison shifts. You beat the index— great. But you still didn’t beat Tom, Dick, and Harry who have outperformed you for years? Where does that pursuit end?

Ultimately, it’s the investor’s choice. There will be some who deny the idea that returns trump all. Picking stocks has so many other worldly benefits, such as education, community, and knowledge of the world. Then there are the more pragmatic of us who say no, a big brain doesn’t feed your family or lifestyle, being right does.

Success looks different depending on where you are in the journey and what your goals are. There is no right answer. There is an abundance of non-performance-related benefits that come from taking an interest in public markets, but at the end of the day, you have to have something to show for your efforts other than a bigger bookshelf and more interesting dinner conversation. There’s no shame in not beating the market. But there’s also no excuse for not trying4— at least, once you know what’s possible.

Thanks for reading,

Conor

Author’s note: In hindsight, I started writing this before Trump’s April tariffs, and now it would appear the date of the tweet was an opportune time to allocate 100% to cash.

Defined as individuals living on less than $2.15 per day, according to World Bank data.

Defined as children who die before their first birthday, according to World Bank data.

I consider a passive ETF strategy “not trying”.

Wow, thank you Conor, for the kind words and the fantastic breakdown.

I am very aligned with the idea that each investor competes with its own goal. In my case, I care about improving my craft so that the "recipe" that led me to do well with Palantir and Robinhood could become quite repeatable over time.

Sharing a public track record is my way of sharing this path against myself.

"Suppose he sold everything, allocated 100% to cash, and did nothing for a decade1. The CAGR would be 17% (before inflation)— a 700 bps surplus to the lifetime CAGR (10%) of the SPDR S&P 500 ETF, SPY."

I confess I thought of this...!

"To repeat the above comment once more highlights the bliss of being an individual. None of that shit really matters to an individual."

I sorta disagree with this.

For the most part, those metrics are supposed to reflect the risk that was taken in achieving the return achieved. I don't subscribe to their methods, for the most part - such as measuring the risk by the volatility - but I agree with their notion. Risk is the idea that more things could have happened than did happen.

I think the distinction as to whether such metrics (or the less tangible thing that they are trying to represent) matter is not so much between the individual and the institution as it is between hindsight and the future. An institution cares about those things because it must now reuse (to some degree) the strategy that produced those returns - and while those returns are known, the future ones are not. The individual has the freedom not to care because he may now, as you say, stick his cash in a savings account and go drink cocktails on the beach.

But if an individual goes to a casino and wins it big, are the risk-adjusted metrics of any relevance to him? In terms of whether such a move was a "good choice" - yes.