Moats & Capital Allocation

Pat Dorsey on what makes a moat

“The outputs of capital allocation & competitive advantage may be quantitative, but the inputs require qualitative evaluation. You can’t screen for switching costs; you have to talk to customers and understand the value proposition. You can’t assume high market share equates to a cost advantage; you have to unpack the unit economics. You can’t trust that management will allocate capital rationally; you have to gather supporting evidence”.

Outsiders may be forgiven for thinking that investors have a peculiar fetish for medieval fortification. Moats are commonly discussed in investor circles. In the literal sense, a moat is a deep and wide trench surrounding the base of a castle and is populated with water. A common castle defence system of the medieval era; a moat made it difficult for enemies to approach the castle as the water drowned them, or slowed them down and made them sitting targets. I happen to live a stone’s throw away from one of Europe’s most famous castles, situated on a picturesque hillside, overlooking the city. While barren of water today, Edinburgh Castle was once the proud owner of a moat.

By the time a man reaches a certain age, 67% develop an acute fascination with history. The other 37% take up a passion for statistics; 83% of which are made-up. Investors’ fascination with moats is the byproduct of one of Buffett’s many metaphors used as a bridge to understand the stock market. While Buffett is credited with coining the analogy, I am not certain when he first mentioned it. But here’s a line he shared during Berkshire Hathaway’s annual shareholder meeting in 1995.

“The most important thing is trying to find a business with a wide and long-lasting moat around it, protecting a terrific economic castle with an honest lord in charge of the castle”.

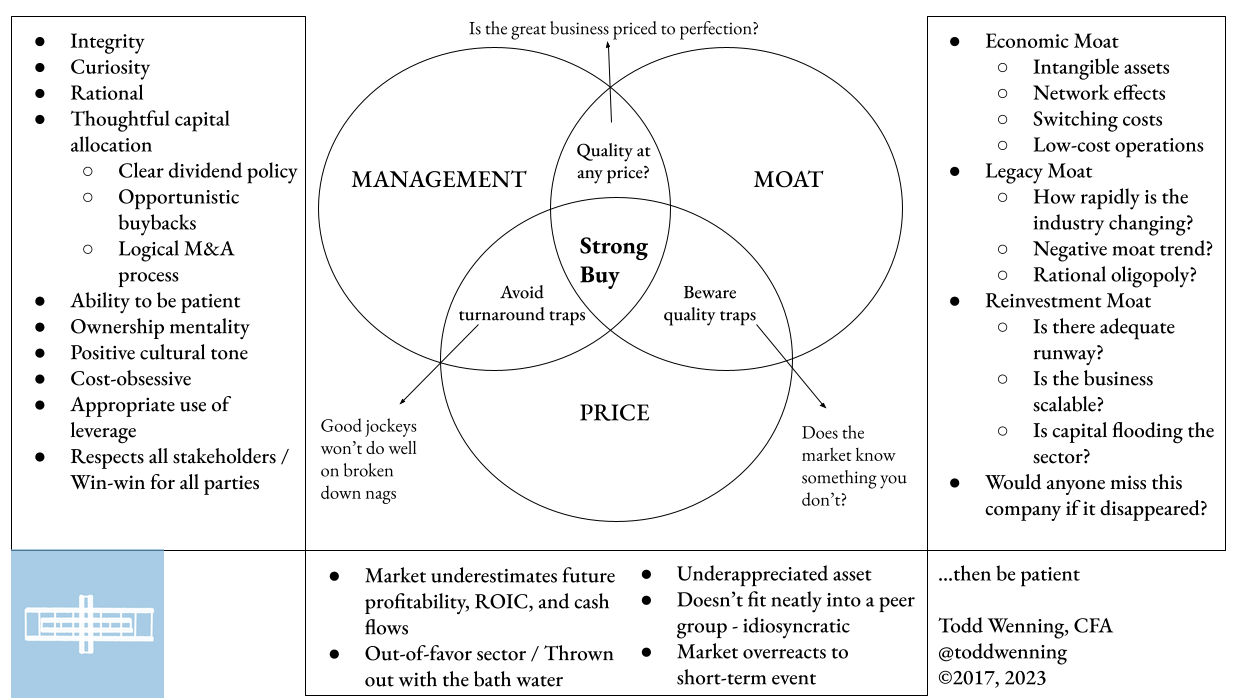

Today there’s an infinite and expanding body of work on moats. Someone who has spent years writing on the topic that I enjoy reading is Todd Wenning; formerly a member of Ensemble Capital and now author of Flyover Stocks. He recently wrote a piece (see honourable mentions) highlighting how the presence of a moat can factor into investment decision-making, as well as how a moat’s absence can lead an investor into various valuation and turnaround traps.

One investor who has further popularised the concept of moats is Pat Dorsey. In his 2008 book, The Little Book That Builds Wealth, the theme centres around Dorsey’s analysis of moats, and the majority of the fourteen chapters are dedicated to individual aspects of moat theory; such as what they are, how to find them, different types of moat, fake moats, and valuing moats. He starts off the first chapter by explaining why moats are so important.

“For most people, it’s common sense to pay more for something that is more durable. From kitchen appliances to cars to houses, items that will last longer are typically able to command higher prices, because the higher up-front cost will be offset by a few more years of use. The same concept applies to the stock market. Durable companies—that is, companies that have strong competitive advantages—are more valuable than companies that are at risk of going from hero to zero in a matter of months because they never had much of an advantage over their competition. This is the biggest reason that economic moats should matter to you as an investor: Companies with moats are more valuable than companies without moats”.

Dorsey has served in a variety of roles throughout his career. Besides being an author, from 2000 to 2011 he acted as the Director of Equity Research for Morningstar, where he led the development of Moringstar’s economic moat ratings and the methodology behind their competitive advantage analysis framework.

Competitive Advantage & Capital Allocation

In 2013, he would form Dorsey Asset Management, where he remains to this day. They recently published a presentation on competitive advantage and capital allocation and, like a good student, I took some notes.

Why moats matter: Basic economics demonstrates that when an industry earns high profits, competitors soon follow. Rising competition then causes returns to fall, business investment declines, firms exit, and then once the supply equation improves returns increase, and the cycle repeats. Very few companies can enjoy long periods of high returns on capital. Possession of structural competitive advantages (aka, economic moats) is one of the commonalities of firms that enjoy lengthy stretches of high returns on capital.

“An extended period of excess ROIC increases business value by lengthening the period during which capital can be reinvested at a high NPV”. The wider the moat, the more durable.

Types of moats: There are believed to be four common varieties of moat.

Intangible assets:

You can’t store them in a warehouse, but they still have value. Some intangibles, like brand value, are qualitative and are by nature difficult to compress into a quantitative value. How much goodwill does the Starbucks brand have today? What is that goodwill worth? How much would it be worth tomorrow if the world suddenly found out the secret ingredient of their espresso was rat droppings? In oligopolistic market structures, product differentiation and brand power can be powerful forces that help fortify a business from competition. Branding is deeply psychological and preys upon a human’s strongest driving force; desire. In other instances, patents, contracts, and relationships can allow companies to control a market.

Brands

Lower search costs. While certain brands capture a majority of mindshare when it comes to their respective consumer base (Tide, McDonald’s, Chipotle, Greggs, Amazon) there are some which have become verbs in their own right (“Google it”, “I’ll Uber to you”).

Strong consumer price inelasticity. In other words, they have pricing power. Goods like fuel will have substantial inelastic demand; if the price of fuel goes up 10% tomorrow, you’ll still buy it because you have to go to work. Starbucks coffee is hardly a necessity and has long been an affordable luxury. However, the last few years have shown consumers’ willingness to continue to swallow up increasingly premium cappuccinos. Not all brands are built the same. Should the price of Heinz beans increase 10% tomorrow, the allure of substitute products, like the supermarket’s own brand of canned beans, would highlight the relatively greater price elasticity of beans. But remember, customers were already paying premium pricing for branded baked beans.

Create propositional value. Think about jewellery for a moment. Does it make sense that certain brands can charge more for precious stones than others? For what amounts to a commodity, Tiffany and its iconic Tiffany blue boxes can command a higher ticket for diamonds than most independent jewellers. Marketing, reputation, differentiation, and desire; are all factors in the fascinating world of brand propositional value. Anyone familiar with the luxury industry will understand this well.

Confer legitimacy. (Gartner, Moody’s, Standard and Poor’s).

Patents

As Dorsey once said; “patent lawyers drive nice cars”. Patents can create temporary protection in some fields, preventing competitors from selling particular products or utilising patented technologies. However, it pays to be cautious of firms that derive a large portion of their earnings from the protection of patents as they are finite in lifespan and can be challenged and/or maneuvered around.

Licenses

In highly regulated industries, regulatory licenses can act as an almost insurmountable barrier to entry, creating legal monopolies or oligopolies; markets that are protected, by law, from competitors. The key lies in finding companies that can price like a monopoly without being regulated like one.

The caveat with intangibles is that brands can rot, patents can expire, and licences can be revoked or de-monopolised with a change in regulatory policy. The irony of large brands is that they stand to lose so much more. While it takes decades to build a reputation, it can take minutes to destroy one. Moreover, as Dorsey suggests, “fragmentation of mass media has dramatically lowered the cost of reaching a mass market”.

Switching Costs

It costs more for a consumer to switch to a competitor than it does to remain with the incumbent; creating sticky consumers. Switching costs come in many forms; time, money, and risk. Why do consumers stay with the same bank for so long when the offers and incentives to switch are rather compelling? It’s a hassle and takes time. Why are people so reluctant to change between iOS and Android operating systems? Because learning a new OS is taxing. Why do incumbent, and archaic, financial research terminals built in the 90s still command such a large market share? Because research terminals are often mission-critical software and the risk of switching is high.

The switching costs are not mutually exclusive either. Suppose you live next door to a supermarket which is, on average, 5% more expensive than the one a 25-minute drive away. The fuel expense may nullify any savings, and it would exhaust 50 minutes of your day with additional transit. It’s just not worth it. Now suppose you consider ordering your weekly grocery shop via an online-only supermarket. Suppose it saves time and money. There you have another decision to make. There is an ugly side to switching costs, whereby a sticky customer becomes a trapped customer. While a CFO and his bottom line might view these as the same thing, in reality, there is a large base of disgruntled customers itching for a new entrant to take their business.

Network Effects

Providing a product or service that increases in value as the number of users expands. This is, in my opinion, the most beautiful and powerful moat. Visa, Mastercard, American Express, Facebook, Instagram, Microsoft Excel, Uber, and Rightmove, are a few examples. It earned its name because of the self-reinforcing nature of the network, spurred initially by a flywheel.

It’s like lightning in a bottle as it scales, and is immensely difficult to replicate. Nowhere is this difficulty more evident than in social networks. BeReal, the Instagram competitor, caught some buzz in 2022 because of its focus on real and spontaneous interactions; a refreshing change from the filtered lifestyle larping engine that is Instagram. By the summer of 2022, BeReal had grown from 900k users to 22 million. By August, MAUs peaked at 74 million and gradually declined to the 25 million estimated today (November 2023). Vine, Periscope, Bluesky, Poke, Mastadon, Clubhouse, Google+, Friendster, YikYak… it’s a long list.

Network effects are maintained by

Subsidising one side of the network: like in the early days of Uber.

Driving engagement: YouTube, Facebook, Instagram.

Network effects are at risk if

The user experience degrades: Like Twitter right now.

Pricing power is abused: Dorsey listed Bloomberg as a pricing power abuser, which naturally intrigued me as I am part of a team looking to take share from Bloomberg. While Bloomberg is the pinnacle of research terminals and is often a mission-critical service for relatively price-insensitive customers, there is a sizeable cohort of Bloomberg users desperate to find alternatives. For some, the price is not justified based on the % of the data they need.

Cost Advantages

Intangibles, switching costs, and network effects are all competitive advantages that can allow a business to be a price setter; controlling how much value it extracts from customers. Some companies can create a competitive advantage by having a structural, sustainable, lower cost of operations than the competition. In a nutshell, they find a cheaper method to deliver a product which can’t be easily replicated. As the size of the business grows, the costs can be spread out over a larger base and reinforce the advantage. RyanAir, Costco, Amazon, Walmart, and IKEA, are some great examples.

Cost advantage is often confused with “low prices”. While cost advantages allow a business to undercut the competition with pricing, in many cases the cost-advantaged business will not be the lowest-priced competitor.

Cost advantages must be durable to sustain a competitive advantage.

In other words, can a competitor easily replicate it?

Shifting manufacturing from Europe to India might save some bps on margin, but could a competitor not follow suit?

What if a company’s operating expenses are structurally lower due to patented technology? That’s a different story.

Cost advantages are mostly found in industries where a large portion of the consumers are price-sensitive; airlines, groceries, homeware.

If there are readily available substitutes in the industry, cost advantages are likely to be a larger factor.

Dorsey categories cost advantages as follows:

Process: Create a cheaper way to deliver a product that can’t be replicated easily (GEICO, Dell, Southwest).

Scale: Spread fixed costs over a large base. Relative size matters more than absolute size (Amazon, Costco, Ryanair).

Niche: Dominate industries with high minimum efficient scale relative to TAM (Constellation Software).

Location: Having an advantageous location, which is hard to replicate. Can create mini or local monopolies (Waste hauliers, supermarkets, commodity extractors).

Unique Assets: Access to a unique, world-class asset (commonly found in commodity businesses).

In order of durability, I would suspect scale is the strongest cost advantage, followed by location, unique assets, niche, and process. While process cost advantages can last a long time, they are most often temporary. Location is an advantage that benefits fewer companies today, given the advent of the internet and low-cost delivery.

What is not a moat: Mistake these as moats at your peril. While most of these factors are not inherently bad (quite the opposite), they are commonly mistaken for competitive advantages. “The single most important thing to remember about moats is that they are structural characteristics of a business that are likely to persist for a number of years, and that would be very hard for a competitor to replicate”.

Dominant market share: In isolation, high absolute market share is not a moat. Companies can fail to maintain market share and fall behind in technology or fail to notice a change in consumer tastes. History has shown that previously dominant companies have given away market share to smaller entrants precisely because they failed to build a moat around their large businesses.

Bigger is not always better. Smaller players in an industry can generate attractive returns on capital.

The important question to ask is “How did they grow their market share?”. Rightmove has long endured a significant stronghold in the UK property market, but because the business has an incredibly strong network effect.

Technology: Most technology is eventually commoditised and disruption is inevitable.

Hot products: Potential to generate excessive short-term returns, but without sustainability, these passing fancies often fall just as hard as they rise.

Management & execution: If you read Dorsey’s first book, you will find a section in the chapter ‘Mistaken Moats’ that argues great management and execution are desirable traits for a business, but that they are not structural competitive advantages. Since then has shifted his perspective on the matter; no longer including the factor in his usual mistaken moats dialogue.

There are edge cases to every situation, sometimes a moat can protect a business from a bad allocator. Other times a great manager can compensate for a lack of competitive advantage.

“A tiny minority of managers can create enormous value via astute capital allocation if they don’t start with great horses”.

The fact stands that great managers look for ways to widen a company’s moat, while bad managers look to reinvest capital outside of a company’s moat, lowering overall ROIC.

What widens a moat? The answer should be part of management’s core strategy.

Improving customer experience, Amazon

Share scale economies, Costco

Increase vehicles on the road, Uber

Drive user engagement, Facebook

Global acceptance, Visa, Mastercard

Capital Allocation: The link between business value and shareholder value. Capital allocation can either destroy or compound business value. Ideally, a business will reinvest capital where the return on investment is greater than the weighted average cost of capital. It makes little sense to do otherwise, yet managers still do it. If the company has high ROIC opportunities (attractive reinvestment runways) it should reinvest heavily. When they don’t have such opportunities, most often these companies will either (a) pay dividends, (b) increase share repurchases, (c) reinvest into non-value-add areas, (d) continue reinvesting into areas with declining ROIC (e) pay down debt, or a combination of the above. Sometimes, except for (c) and (d), these activities are good uses of capital.

“If capital is deployed in ways that amplify value, shareholders benefit from both increased business value and from value-accretive actions. Value compounds”. Some home truths:

Internal growth is not normatively good.

Dividends, if funded poorly or paid in place of more attractive opportunities, and share repurchases, if executed above intrinsic value, are value destructive.

M&A is most often a poor capital allocation; particularly during periods of excess in markets.

“The bigger the deal & the less similarity between buyer and target, the more likely $$ will be torched”.

“If M&A is to have even a faint hope of creating value, it must be a central part of strategy”.

Assessing capital allocation: Rules of thumb for establishing management’s competency.

Look at the past 10 to 15 years of financials

Has the share count increased or decreased?

When did large changes happen? Why?

Are they a share cannibal or a serial dilluter?

Look at the CF statement for evidence of M&A.

How much was paid?

What was the result?

What is their hit rate on successful vs unsuccessful M&A?

Did the company simultaneously pay a dividend and tap capital markets?

How are dividends and repurchases funded?

At what value are they repurchasing their shares?

If ROIC has declined, is capital being returned?

Does M&A serve strategic goals, or does it paper over strategic failures?

How many times did they say “synergy” in their M&A filing?

How related is the M&A target to the existing business?

Read the annual report, MD&A and proxies

Is capital allocation discussed explicitly and rationally?

Are words consistent with actions?

Are actions & words consistent over time?

What are the CEO’s incentives?

How do they get paid?

Is there any ROI component?

Is M&A included in compensation targets?

“Managers who are paid handsomely to misallocate capital will do so. Incentives matter”.

Below you can find the presentation, as well as a few other useful items on moats that will keep you occupied.

Thanks for reading,

Conor

Honourable Mentions

Here is some other great stuff worthy of your time. Because the topic of the day is moats, these are all moat-related.

Dorsey Asset Management’s presentation on competitive advantage and capital allocation, 2023.

Pat Dorsey speaks to the Manual of Ideas in 2012 in an interview that is almost exclusively about moats; what they are, how to identify them, common misconceptions, varieties of moats, network effects, reinvestment runways, and a plethora of examples; some of which are still relevant ten years later.

Another Pat Dorsey interview with YIS in 2017, with a broader subject range but with some great insights into moats.

Todd Wenning on the risks of missing a moat, quality management, and valuation.

Cool article. I do software and moats are super hard. I’d be interested to chat on how you’re trying to niche in against the terminal.

Great article. One of the under-appreciated aspects of moats that I’ve found is that the herd spots them quickly and will rapidly deplete the attractiveness of the investment through premium valuations. I’ve been thinking recently about ways to identify moats before the wider investing public catches on. Curious if you have any thoughts there?