Investment Maxims Are Not One-Size-Fits-All

Caveats to Conventional Investing Wisdoms

“Of course that's your contention. You're a first-year investor. You just got finished reading some deep value historian, Ben Graham probably, you’re gonna be convinced of net-nets until next month when you get to Warren Buffett, then you’re gonna be talking about how Graham’s ideas are antiquated and that you simply have to buy and hold quality, letting time arbitrage do its thing. That's gonna last until next year, you’re gonna be in here regurgitating Fisher and Lynch, talkin’ about, you know, the importance of placing more emphasis on qualitative analysis in your investment process. Shortly after that, you’ll discover Druckenmiller, parroting that we should never invest in the present and that buying decisions should be based on what you believe the environment or prospects will be like 18-24 months from today”

Of Course That's Your Contention

An investor’s formative years are not too dissimilar from the bar scene in Good Will Hunting. As infantile investors disembark from the dock and paddle into what feels like an ocean of “unknown unknowns” they cling to whatever fabricates the feeling of a deeper level of understanding. They want to feel confident in their stock-picking abilities; like they are steering the ship, and not flirting with the peril of capsizing.

It helps that the most frequently recited investment axioms make it all feel so simple.

“Buy quality, don’t overpay, and do nothing” - Terry Smith

Recite this line to an amateur and a professional and the two will have profoundly different conclusions. Simplicity requires an incredible amount of hard work to accomplish and the knowledge to appreciate it. Or as Steve Jobs once said, “simple can be harder than complex". A novice may take Smith’s words at face value. An investor worth their salt will notice three questions that ought to be answered.

“I would not give a fig for the simplicity this side of complexity, but I would give my life for the simplicity on the other side of complexity.”

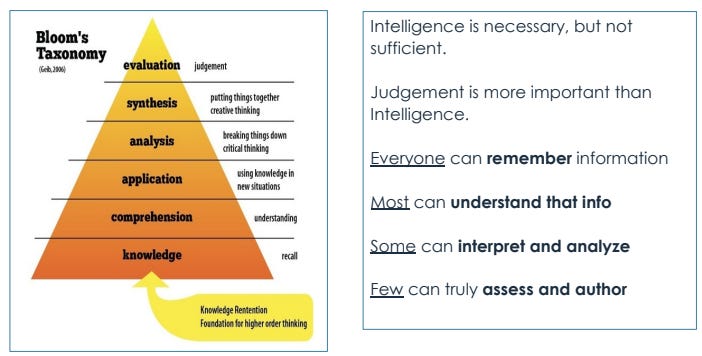

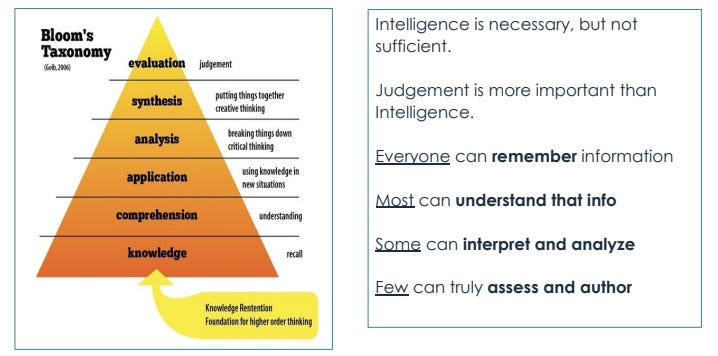

The hierarchy of Bloom’s Taxonomy1 ranks knowledge & comprehension at the base of the pyramid. The pyramid implies that comprehension is a skill anyone can master, but critical evaluation is where so few excel. In the investing world knowledge & comprehension are often mistakenly thought to be at the top of the structure; “okay, I get how Starbucks operates, I understand the history, and I know how they plan to expand in the future, job done”. This line of thought bears no reflection on what consensus thinks vs what you think that they are not seeing. Anyone who has read Howard Marks will tell you that it’s not enough to be right; you have to be right when others are wrong. Michael Mauboussin covers expectations investing particularly well in a book which bears the same name.

Investment maxims possess a beautiful irony; a dichotomy between simplicity and complexity. On the one hand, they are elegantly simple; to evoke mass appeal. But a maxim is like a trap door; resting atop a deep cavern; coated in a sticky web of nuance. Glance at an iPhone and you see a sleek, powerful, extension of the human form; capable of doing almost anything. Underpinning that simplicity is the incredible software and hardware innovation that humans now take for granted2. Simplicity requires an incredible amount of hard work to accomplish and the knowledge to appreciate it. Because investment maxims are simple, the nuance is often overlooked. Not only are they misunderstood but they are also mistaken to be a one-size-fits-all solution to the stock market. What might be perfectly good advice to one, is not applicable to another.

The notion that “diversification is ignorance” could be a destructive piece of advice for a beginner. Failing to grasp the true meaning, they could assume this means simply owning fewer stocks. They may then construct a small basket of concentrated positions, all within the same factor, on the back of that newfound knowledge. Put differently, maxims like this require the knowledge to appreciate it. Have you ever been asked a question by someone less experienced than yourself to which you respond with a watered-down version of the answer? At the conclusion of that response, there is often a desire to add “buts” and “well in most cases”, and “well sometimes…”. There is a tail of caveats that can be overwhelming for someone who doesn’t yet have the base knowledge to fully absorb and/or understand them yet.

Branching out from mere discrepancies in knowledge, conversations about the stock market typically involve investors of differing backgrounds, ethical standards, schools of thought, investment styles, goals, wants, and perspectives. These variables are seldom taken into account in public discourse. Most often two (or more) parties talk over one another; seeking only to get their point across and not considering the perspective of the other party. Today I want to run through some “conventional wisdom” of the stock market and attempt to add what they so often lack when brought up in discussion; context.

1) Diversification is Ignorance

Basis: People rarely have more than 20 great ideas in their lifetime, so why waste capital on your 25th best idea?

Caveat: This assumes that it is the goal of every investor to maximise returns and that they possess the foresight to “only invest in their best ideas”. Easier to say in hindsight.

Nick Sleep once said, “the church of diversification, in whose pews the professional fund management industry sits, proposes many holdings. They do this not because managers have so many insights, but so few!". It’s no secret that the asset management racket is set up to collect fees. Theory will show the benefits of diversification (real diversification) decay quickly once the number of stocks in the portfolio climbs past 10 holdings. There will come a point when each incremental addition begins to exhibit diminishing returns as far as the relationship between expected return and the standard deviation is concerned. This isn’t true if the basket contains 10 cybersecurity stocks, however.

For all intents and purposes, an investor owning 50 stocks may well be exposed to the same amount of market risk or volatility as one who owns 25. But Peter Lynch owned thousands of stocks at once, some might retort. Peter Lynch also managed well over $10 billion and had a team of analysts. The circumstances of which are not comparable to that of an individual investor. This might be sage advice to a professional, whose job it is to generate market-beating or non-correlative returns. But to a retail investor, it’s not so straightforward, and here are a few thoughts as to why.

Most investors are ignorant, succumb to various biases, and overestimate their own intelligence, insight, and conviction.

Most new investors are even more ignorant, having not yet crossed the valley of despair and coming to the realisation that “oh, this is hard”.

Perhaps it’s not terrible advice for a retail investor to hedge against their own ignorance until they learn that diversification is not simply more stocks of the same factor.

I believe that encouraging an amateur to run a highly concentrated portfolio of their highest conviction ideas is the best way to lose their shirt, fast. It is likely their conviction is borne on a bedrock of comprehension, not evaluation.

The advice pays no credence to the time an investor has to study stocks. A full-time investor may have more free time to develop conviction and utilise their network to gain insights, whereas a part-timer might be limited in that regard.

The idea is that diversification is ignorance can be true. But so too can the idea that diversification is protection against ignorance. What I think this topic often lacks is a clear understanding of whether or not the parties are talking about diversification or diworsification, and the extenuating circumstances that drive an investor’s goals and incentives. In the last few years I have witnessed investors similarly aged to myself tout their concentration; only to instead own a small basket of highly correlated stocks. One or more of their stocks go crushed, and they replaced them with new, highly correlated, stocks. They get crushed again. All the while succumbing to recurring bouts of permanent capital loss. Tragic. In this manner, it’s not hard to see that an investor may own 5 stocks in non-related industries and be more diversified than one who owns 25 stocks with a correlation of 1.

2) Ignore Macro if You Are a Long-Term Investor

• Basis: The majority of macroeconomic data is backward looking and the successful projection of said data ranges from difficult to impossible. Focus on what is important and knowable.

• Caveat: The correlation between the stock market and the economy oscillates throughout cycles, but history has long shown the two are intrinsically linked. If you are an investor in cyclical industries, you probably should pay attention to macro.

I find that the general interest in the macroeconomy increases during the bad times, as investors look to rationalise why their stocks struggle. Inflation is bad for equities in the short term, but over the long-term security prices tend to absorb inflation. Central bank stimulus and low-rate environments; they decrease the cost of borrowing and increase the amount of free money sloshing around in the system. Central banks and governments execute expansionary and contractionary policies; the only constant is that they will continue to oscillate between the two. Great businesses survive nonetheless.

→ To a fool, there is one reason to explain why a stock goes up and thousands of reasons to explain why they fall.

→ On the way up, they are investors. On the way down, they become economists.Peter Lynch once said spending 13 minutes a year on macro is 10 minutes wasted. Warren Buffett often denounces the act of trying to predict interest rates as futile. Someone else once said that macro forecasters exist to make astrologers look respectable. These are humorous quips that relate to the profession’s title as the “dismal science”. To paraphrase Michael Burry (who was talking about investing) economics is “neither science nor art - it is a scientific art”. I don’t think anyone should be attempting to predict inflation or interest rates in the near term if they consider themselves to be a long-term investor. But, studying the economy is a broad indicator of health (from investment flows to behaviour at a consumer level) for markets the businesses you follow may be situated in.

Are rising credit-card defaults going to afflict pain on your lender’s portfolio? Is a weakening of demand for vehicles going to hurt the top line of your auto insurer or manufacturer? Is a strong dollar going to benefit the British company you own that generates a significant sum of its revenue in the United States? If you are invested in a business with a sizeable variable cost devoted to a single commodity, should you not understand that market? These are all insights that may be extracted from studying the state of the macroeconomy. The extent to which companies are “exposed” to the economy varies, but perhaps the assertion we ought to completely ignore macro is a naive one. The root of this saying, I believe, stems from the idea that we should avoid being macro forecasters or making long-term decisions based on short-term, backwards-looking, data. The stock market tends to recover before the economy does3. But don't conflate that with the idea markets exist in a vacuum, void of any external influence on the macro level because they don't.

3) Small Caps are Dangerous

Basis: Stocks that are small enough to be excluded from coverage by the masses are likely to trade less efficiently, contain more nasty surprises, and be more volatile.

Caveat: The supposed dangers of small caps also act as their advantages.

There are thousands of companies out there that are too small to be analysed or picked up by funds, discussed in the media, are capture wide appeal. In an environment where the retail investor has so few edges, attempting to uncover which small caps are diamonds in the rough can lead to the uncovering of future multi-baggers; aided by continuous improvement in the business but also flows of investment when they become large enough to attract funds. That said, because these companies are often ignored, the number of potential landmines is greater; in that, there is not an army of sleuths dissecting the filings daily with the intention of uncovering them. What insight can a 20-something investor bring to the public discussion about a company as large as Apple that hasn’t already been told? Conversely, the prospect of gaining an informational edge in a small cap is far greater. The critical distinction here is that inefficiency means the security can be wildly underpriced or overpriced, so it’s a dual-edged sword.

I would assume that an inexperienced analyst is more susceptible to landmines in small caps, but the ‘safety net’ of large caps is not as sturdy as they are thought to be.

4) Large Caps are Safe as Houses

Basis: Large caps tend to be more secure businesses, with established operations, and trade more efficiently on account of the fact they are so well covered.

Caveat: Markets are voting machines in the short term and can remain irrational longer than you can remain solvent.

There are a number of problems with this ideology, so much so that I could write about it all day. Instead, I’ll pluck out what I deem to be the two most important caveats. Firstly, we exist in a world of innovation. While there are businesses that exhibit Lindy Effect qualities (Coca Cola, tobacco companies, stock exchanges, et al) take a look at the largest ten constituents of the S&P 500 over the last 100 years; they change more often than one might think. Secondly, the most important distinction to make here is that, with any size of business, it depends on the value you acquire it for. Price is what you pay, value is what you get.

• Great business priced as bad business → GOOD

• Great business priced as great business → MEH

• Great business prices as amazing business → BAD

Sure, there are times when overpaying for a great business still works out in the long run. But as a general rule of thumb go back to the conclusions of maxim number one. Most investors overestimate their intelligence. For that reason, I suspect that focusing more attention on the value paid vs simply finding great businesses at any price, will save investors a great deal of pain in the long run. At the peak of the pandemic bubble, I saw a reasonably well-known guru state, without sarcasm, that they don’t even look at valuations when buying businesses because they only buy the world’s best businesses. Ignorance is bliss. From 2021 through 2022, many of the world’s largest caps fell 50% or more within a 12-month timespan. Are they still great companies? I suspect so. The issue is, I suspect that for a brief moment in time, they were great companies valued as amazing companies. Hence, it’s not the size that matters, it’s the value.

5) Stick to Your Circle of Competence

Basis: The area you are most likely to have an edge is within your small area of relative expertise, so stick to it.

Caveat: To remain fixed in one place, is to scoff at the prospect of evolution. Investors need to delicately and deliberately expand their circle of competence over time.

This isn’t going to divulge into a debate about being a specialist vs a generalist. As you mature it can be easy to get comfortable in your niche. To prevent stagnation and the downsides of the endowment effect, investors should seek to identify opportunities to expand their circle of competence. As you explore new areas, the cocktail party effect4 comes into play and you will develop a more rounded understanding of the market at large. I would argue this is perhaps more important for a seasoned investor, while a novice should, at first, stick within the parameters of their skillset whilst they learn the ropes.

6) The Most Important Quality for an Investor is Temperament, Not Intellect

Basis: The investor’s worst enemy is themself; emotions are often the leading variable in poor performance.

Caveat: You require a suitable base of knowledge and understanding first. Further, you require the powers of critical evaluation to know (or reasonably deduce) when it is appropriate to “do nothing” and when it is not.

To defy the words of Warren Buffett is bold, but let’s do it anyway. For reference, I would also bucket “inactivity is doing something” and “buy and hold” with this maxim. This one ties into the damaging oath that many investors swear (often with blood) that one can simply “buy quality stocks and hold for the long term” and everything will work out in the end. So much nuance is lost. What is a quality stock? How long is the long term? What happens if you are wrong? What if the thesis changes? Subscribing to this logic without question may result in an investor patiently drawing their portfolio down to a pulp.

“But Amazon?!”

There is a small handful of outliers that buck the trend, Amazon being one of them (which is another wholly misunderstood conclusion in its own right) but survivorship bias is strong and the graveyard of fallen angels is swelling at the seams. Thankfully, they build additional capacity as each year passes. There is no street cred for holding a stock for 20 years; a romanticised concept though it may be. Where this idea gets conflated is that investors need to admit to themselves whether they are “holding quality” or that they are simply prepared to coffee can stocks even if the business strays far from the path that led to the initial investment. A more suitable framework for those who wish to “buy and hold” is “buy, recurringly verify, and hold so long as the thesis remains intact or you can reasonably accept the new thesis”. Not quite as catchy though. You may have strong opinions, but keep them on a loose leash. Which leads me nicely to my next maxim.

7) Time Horizon of Forever

Basis: The best holding period is forever; granting the opportunity to enjoy uninterrupted compounding at high rates over long periods of time.

Caveat: The average lifespan of a company within the S&P 500 index has fallen from 35 to 20 years since the 1980s.

Firstly it’s important to establish whether this is a law that investors hold themself accountable to or a mindset. The mindset that each investment ought to be made with the ideal time horizon being forever is what I believe Buffett is really saying when he talks about holding stocks forever. Instead, some investors take his words at face value and confuse the maxim with a warped version of “buy and hold forever”; regardless of what happens in between.

If you have done the work to develop conviction, only then can you reasonably “do nothing” during moments of volatility, if you believe you know something the market underappreciates. That said, possess the humility (or paranoia, whatever works best for your personality) to know that you may be wrong, and work hard to find out why you might be. Conviction is not blind faith.

8) Buying Indexes is The Best Decision for Most Investors

Basis: Most fund managers fail to beat their respective benchmarks over the long term, and data shows that retail investors fare no better. Buy the index and spend the ungodly amount of time you would have spent studying stocks to enjoy the finite amount of time we have on this earth.

Caveat: Most of this argument is centred around buying the S&P 500, an index that has only gone up and to the right so long as it has existed. Whether it be hot hand fallacy5 or unbridled belief in the US economy, the same advice doesn't translate so well across emerging markets; even in developed markets, such as Japan and the UK. Avoiding a full-blown discussion of the merits of the security itself (ETFs) and the rise of passive investing, I will keep it short.

• Some investors enjoy the act of researching stocks. It evokes continuous learning and furthers our understanding of the world and businesses around us. It’s a “passion outlet” for many, and whilst beating the market may be a goal, it’s not their sole purpose for picking stocks.

• For the busy individual, someone who wants to accumulate wealth over and above the rate of inflation over their lifetime, and who has no interest in learning how to analyse a balance sheet, buying a mixture of indexes is likely their best shot at doing so.

• Some argue the narrative that the market is so hard to defeat has resulted in a mass of investors “settling for average” returns by simply buying indexes. For those with the time, resources, and passion, I think they ought not to settle for average. Striving to beat the market takes some amount of arrogance, and that’s perfectly fine.

At the end of the day, you can do both; allocate a portion of wealth to passive instruments, and some towards picking stocks. All in all, it boils down to “do what you feel is best for yourself and your own circumstances”, don’t judge others, and focus on your own lane.

9) DCF Models are Necessary

Basis: Discounted cash flow models allow for granular insight into whether or not a security is ‘worthwhile’ using the time value of money to discount future cash flows.

Caveat: The further out you project, the more likely you are to be wrong.

On a personal note, I am a fan of the discounted cash flow model, largely as a thought exercise or to quantify assumptions. My preference is for a reverse DCF which, in plain English, reverse engineers the model; allowing the user to set a goalpost and then determine which input assumptions have to be made to reach the said goalpost; then dissecting whether or not you feel they are viable inputs. But neither method is perfect, nor necessary, in my opinion. The number of times someone sent me a DCF model during the pandemic bubble that has now been rendered useless…

A model is only as good as its inputs, and for all intents and purposes, projecting the future cash flows of a business is guesswork. How many models built in 2018/19 had a global pandemic priced into them? How many analysts accurately predicted the kamikaze into the metaverse from Meta? The higher up the professional ladder you go (metaphorically, I wouldn’t know…) the more ‘sophisticated’ valuation methods become. On some level, it’s needed (these people earn ungodly fees and have to do something right?). On the other hand, the deeper you get into it, the more you realise it’s fugazi; a comfort blanket, an attempt to create the illusion that these forecasters know what the price of a security will do in the short to medium term. I do not believe that a retail investor requires a DCF model to determine a quality business. There are two extremes of a spectrum. On one side, staunch quantitative investors who ignore qualitative evidence. On the other, hardened growth investors who invest in narratives and not numbers. I think it’s best to be somewhere in between the two, but there are many ways to make money in the stock market.

Honourable Mentions

• It worked for me: So what.

• Multiples are useless: In isolation, yes they are. Even when conducting relative industry peer analysis they can be useless for this ignores the relative premium/discount that the industry trades at. Business A might be priced at a discount to its peer with similar growth prospects, but if the industry as a whole is at the peak of a valuation cycle, that has to be considered. That said, there are instances where multiple valuations can be used to extend one’s research. It can provoke further lines of questioning.

• Sell when the thesis changes: Often used as a scapegoat to sell underperforming stocks. Relates to maxim number one, and requires the assumption of understanding.

• DCA cures all: DCA’ing into terrible companies does not.

• Stocks always go up in the long run: What is your definition of “stocks?”. This relates to maxim eight, where people use the S&P 500 as a proxy for everything related to the stock market. A dangerous mentality to possess.

• CFAs know better: Most people who rag on the CFA tried it and found it too hard. Then there are some who attained one and have the right to rag on it. The certification can be a viable foot in the door towards a career in the industry (sometimes a prerequisite), but in the same way, putting a lab coat on doesn’t make you smarter, a CFA won’t make you a better investor. It is a great way to develop a solid foundation of knowledge across a wide array of topic matters, however. I never completed mine (life got busy), but don’t regret the time I dedicated to studying the first two levels.

• Dividends are a waste of time for young investors: The argument here is that as far as capital allocation goes, dividends can imply a lack of attractive opportunities for reinvestment. Secondly, at such a young age the goal ought to be optimising for capital appreciation to maximise the amount of capital one has to compound over their lifetime. Caveat one, mind your own business. Caveat two, the compounded effect of tax-exempt dividends is often underappreciated. Caveat three, consider that some investors want an element of cash flow in their portfolio. It reminds me of the debate about owning a house outright. Some will argue that due to the time value of money, the stock market affords a greater opportunity for return on your capital than accelerating your mortgage payments. That might be true (assuming someone can earn a solid return in the first place) but some people like the peace of mind of owning their home. At the end of the day, who really cares?

• Because something isn’t working, don’t change your mind: Some amount of persistence and patience is needed in investing, but carrying this idea into ideas you are wrong about, is a recipe for pain. Have strong opinions, keep them loosely held, and be paranoid that you are wrong and open to changing your mind if the facts dictate you ought to.

• Using outliers as confirmatory evidence: Just don’t. The only person you are hurting is yourself.

Anything you’d like to add? Any areas you feel I have missed or am incorrect about? Fire them in the comments section.

Thanks for reading and have a happy Christmas if you happen to celebrate it.

Conor

The pyramid implies that comprehension is a skill anyone can master, but that critical judgement is where so few excel. In the investing world, particularly amongst novices, knowledge is often mistaken for understanding. This resource by Krainos Capital is solid for further research on the matter.

I subscribe to the notion that smartphones (regardless of producer) are vastly underappreciated in the modern-day first world.

The cocktail party effect is the name given to a phenomenon describing the brain’s ability to tune out the noise at a party and focus on the person’s voice with whom you share a conversation. The ability to focus one's auditory attention on a particular stimulus while filtering out a range of other stimuli. For more on this, see here.

The hot-hand fallacy describes our tendency to believe that a successful streak is likely to lead to further success. For example, if a basketball player has made three consecutive shots, we may believe he has a greater chance of making the fourth than is actually likely.

Great note Conor!

Agree on the macro one with a caveat. If you pick a great businesses run by a great owner/manager, are those managers who in the long run will make your job as an investor easier by making good capital allocation decisions for you.

Great piece, Conor! Curious if there was a report you grabbed the image for point #8 from?