Why Are We Drawn to Low Probability?

We spend far too much time focusing on how to win the game we are playing, rather than understanding the reasons we are playing at all

Ignoring your health, forgoing insurance, inadequate digital security, not using sunscreen. These are examples of high-stakes low-reward games. Choosing not to wear a seatbelt —what are the rewards? A modest improvement in comfort. What are the risks? At best, whiplash. At worst, a trip through the windshield. In each case, the perceived rewards are relatively small while the stakes can be incredibly high. Yet we do them anyway. The effort required to nullify the risk is often a minor inconvenience. So what gives?

A few weeks ago I read a piece by Joe Wiggins that asked why investors play low-probability games. He said, “Being an investor is like walking into a casino and seeing everyone crowded around a table playing the game with the worst odds of success”. The odds of “positive outcomes are poor, yet we carry on regardless”, he continues. There is some subtext to unpack here of course. What is a ‘positive outcome’ to you might look different to me. For some, it’s an ambiguous desire to beat inflation, earn more than a checking account interest rate, or compound wealth over time. For others, it’s a desire to ‘beat the market’ or an equivalent barometer of success.

In the case of the latter, Joe is astutely correct. The odds of an individual earning a surplus return to the S&P 500 over a lifetime are incredibly slim. Yet they attempt it anyway. Wiggins’ essay is concise and proceeds to list several reasons why investors are drawn to low-probability games. I am particularly fond of his concluding remark.

“As investors we spend far too much time focusing on how to win the game we are playing, rather than understanding the reasons we are playing at all”.

- Joe Wiggins, Why Do Investors Play Low Probability Games?

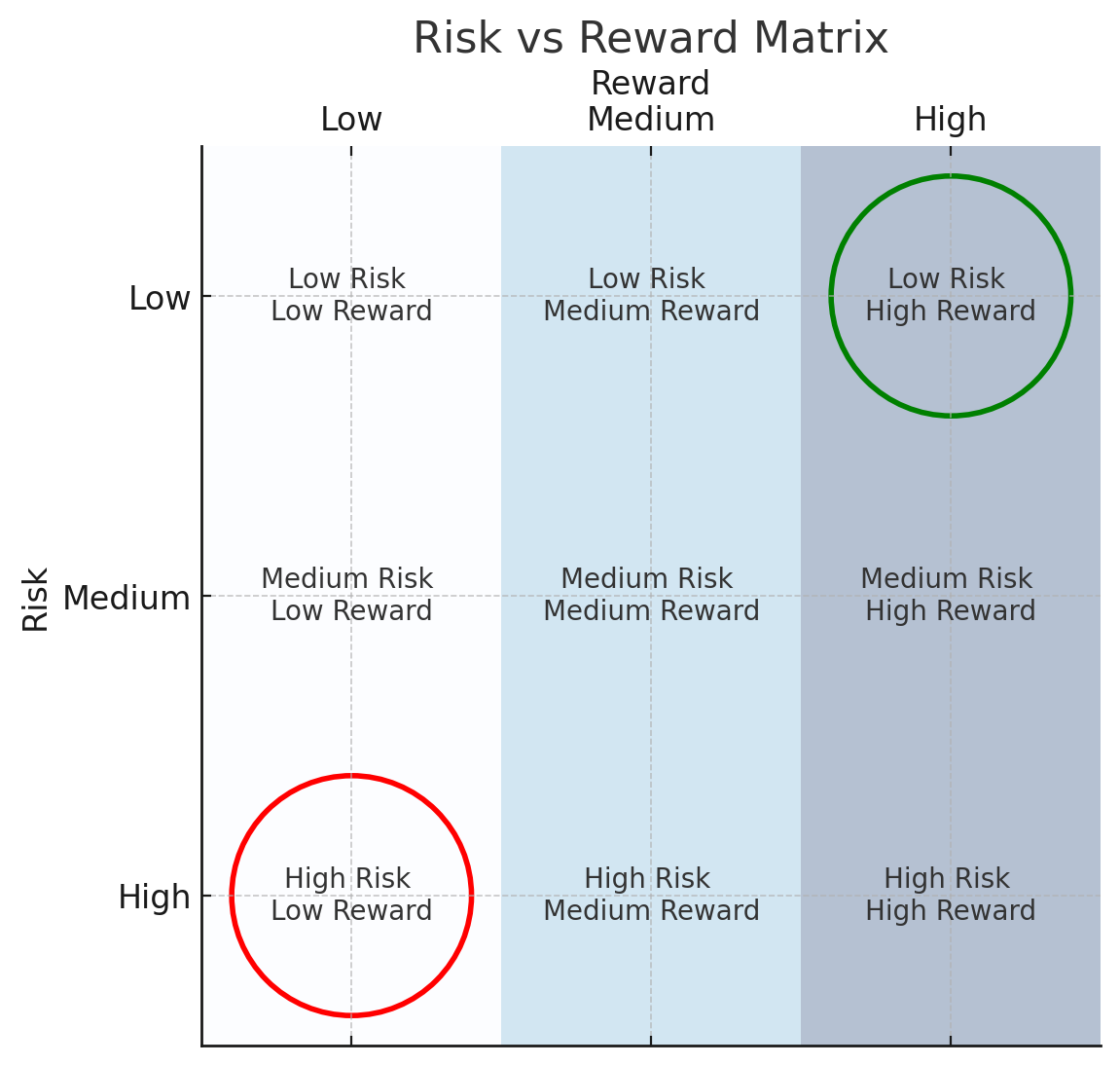

Just as investors persist in chasing improbable gains, our daily decisions are often marked by similar contradictions where small rewards lure us into significant risks. In general, we should avoid putting ourselves in situations with high risk and low reward. The earlier examples have two things in common; the perceived probability of a negative outcome often feels small, negligible even, and the risk-to-reward dynamic is skewed, with the potential risks far outweighing the minimal rewards. We convince ourselves that "it won't happen to me”.

Humans have a penchant for cognitive dissonance. When we hold two contradictory beliefs or feelings we are motivated to pick a winner; thus eliminating inconsistency and reducing anxiety as we alter our beliefs or actions to complement the desired outcome.

Every smoker knows that smoking is harmful. Every smoker relishes the soothing hit of dopamine that coats their brain’s reward system when they take a drag. The desire to feel that dopamine is so strong that the addiction triumphs; and so continuing to smoke despite being aware of its harm is an example of cognitive dissonance. Emotions are an unfathomably powerful motivator. They are the world’s greatest gaslighter. They are capable of blinding us to reality in pursuit of desire.

Something which is intrinsically linked to emotion is our fundamental belief system; whether born of culture, environment, or personal experience, it shapes how we view the world and often overrides logic. These beliefs tend to encourage cognitive dissonance too. Factors like our tendency to be risk-averse, or our need to feel like we are in control.

Road vs Air

These two foundational human attributes are often in conflict with the world around us. The difference in how safe we feel when flying on commercial aircraft vs. driving down the motorway is a great example. Air travel is the safest form of transport. The rate of incidents per journey is significantly lower than a road-bound vehicle. Yet, it’s common to know someone afraid of flying and rare to know someone unwilling to step foot in a car.

Travel 100,000 miles by car and there is a ~4.8% chance you will be injured to some degree1. The same distance by aircraft is as good as 0%. The World Bank estimates that there are 0.05 fatalities per million aircraft passengers. In other words, about 1 fatality for every 20 million passengers. They also estimate there are 135 fatalities per million passengers for vehicles or about 1 fatality for every 7,407 passengers. Ceteris paribus, you are more likely to be injured in a vehicle than an aircraft.

Vehicular death rates vary globally. Developed nations with better infrastructure and rule of law typically see fewer fatalities. But the point stands, it’s much safer to travel by air. Where we humans get hung up is that the negative outcome of an incident in the air is near certain death. In a binary fashion, we either survive or face catastrophe. On the other hand, the range of outcomes of an incident in a car is more palatable. This is all to say that we are generally irrational in how we perceive the relationship between risk and reward or probabilities.

DCF: Dillusion of Control Framework

The discounted cash flow model is a means to an end. It can also help us understand how we deceive ourselves in pursuit of the need to be in control. You plug in some inputs and those inputs estimate the fair value of an investment based on its expected future cash flows, adjusted to account for the time value of money. A reverse discounted cash flow model flips the hierarchy so that you start with a current value and work backwards to find the required inputs for said current valuation. In other words, you are measuring the implied expectations and deciding if they are acceptable.

They can be immensely useful, and equally precarious. Investing has a scare factor. It’s uncertain, the future is unknowable, and there is an infinite concoction of variables that can influence the outcome both within and outside the company’s control. The most influential factor is your own decision-making and temperament.

Wouldn’t it be nice if there was a tool that we plug numbers into and tells us if something is a buy or a sell at the current price? Doesn’t that just make life easier? It washes all of the uncertainty away. Investors can subconsciously fall into the trap of forgetting that models are not a get-out-of-uncertainty-free card.

Ben Graham’s concept of ‘intrinsic value’, later popularised by Warren Buffett, is flawed in that it’s entirely conjectural. Both intrinsic value and fair value are theoretical constructs, meaning they aren’t “real” in the sense that they’re not fixed or universally agreed upon. Instead, they represent estimates of what an asset is truly worth, based on different models, assumptions, and perspectives. In short, while the methodology used to derive an output is quantitative, the output itself is then subject to subjectivity. It’s a matter of opinion, and the saying goes that opinions are like arseholes…. everybody has one.

An investor will never be in control of the market. The best they can do is succumb to that reality and find a way to deal with it. Focus on the variables they do have control over. Ensure they have a process which eliminates as much undesired human behaviour as possible. One that nurtures rational thinking and common sense. If you know you are sailing through the waters of Siren, the best thing to do is tie yourself to the mast or cover your ears.

Something as simple as a cash flow model, when relied upon too extensively, can confound the fear of not being in control and create the illusion that we are.

High-Risk Low-Probability

Until now i’ve used the notion of stakes and risk or reward and probability interchangeably, but they are not the same. The terms high stakes, low reward and high risk, low probability are different dimensions of decision-making that have some overlapping matter. The best way I can describe it is through the roulette table.

High Stakes, Low Reward: You play by betting on red or black

Stakes: You can bet a significant amount of money (high stakes), but the potential reward is minimal (only doubling your bet). The odds of winning are close to 50%.

Low Reward: Even if you win, the reward is small compared to the amount at risk. You double your money, but the risk (losing your entire bet) is large for what you stand to gain.

High Risk, Low Probability: You play by betting on a single number

Risk: The risk is still high (you could lose everything you bet), but the reward is significantly higher, at 35 times your bet.

Low Probability: The reward may be higher, but now the probability of winning is extremely low. Depending on where you are in the world, the probability is 1 in 37 (2.7%) or 1 in 38 (2.63%).

It can be useful to tackle decision-making through both lenses, but I would argue in favour of taking a risk-probability approach. The idea of ‘reward’ flirts with subjectivity while ‘probability’ is closer to a universal truth. Whatever game you find yourself contemplating, it’s best to think about what you stand to lose, what you stand to gain, and what the probability of a positive and negative outcome is.

Why Are We Drawn to Low Probability?

Taking one of Wiggins’ examples, he suggests that being “uncommonly skilful” is “the only reason to engage in a game where the odds for the average player are poor”. If a peak Roger Federer participated in a knock-out tennis tournament of 100 players, the basic odds of success (winning the competition) is 1 in 100 (1%) for the average player. For Federer, they would be considerably higher, and so he should play. I don’t know exactly how to calculate that, but it’s undoubtedly true.

The perception of elevated skill, accurate or not, can result in willful ignorance. Through that ignorance, we may be motivated to engage in activities in which the probability of success is considerably lower than what we believe. The problem with investing, in particular, is that everyone thinks they are the 5% when it comes to beating the market. Despite knowing the odds of success are slim, seasoned investors believe they can defy the odds anyway. That’s willful ignorance, but what about plain old ignorance?

The term ‘ignorance is bliss’ means that you don’t know what you don’t know. Your understanding of the game is so limited, that you are deeply unaware of your own ignorance. Much like you shouldn’t scold a child for repeating something a parent has said, it’s hard to criticise the blissfully unaware. Only through experience, can ignorance be chipped away. I believe the trajectory for many investors is they start investing with the desire to beat the market because they don’t know any better. Over time, every rational investor appreciates how difficult this is in reality. They will reach a crossroads, and the paths diverge:

Willful ignorance: They continue under the belief that they will defy the odds.

Graceful acceptance: They continue despite the realization that they are unlikely to beat the market. Perhaps they change their goals to be less centred around ‘beating the market’. For many, investing is fun. It’s a way to understand the world while growing wealth over time. Despite what some might say, there is not only one reason to invest.

Beach mode: They continue to invest, but reallocate into funds or other passive investments. They exit, or significantly reduce, their exposure to individual stocks and settle for ‘market’ returns. They have more time to enjoy their limited time on earth.

Sometimes, the fact we know the odds of success are so low creates an element of excitement. Remember the internet sensation that was the ‘bottle flip’ challenge? You take a water bottle by the neck, flip it, and try to make it land upright. Before realising the ‘trick’ to make it land upright every time, it’s a difficult task. The odds of success are low, but it’s fun so we try it another 20 times. What about carnival games? By this point, I think everyone knows each game at a carnival has an element of rigging to ensure customers seldom win and take home a prize. We know this, we know the odds of success are slim, but that makes it fun and that much more satisfying when we do win. With investing, however, fun is usually not a great sign. If you are passionate about it, it can certainly be enjoyable, but as Wiggins correctly remarks, “The challenge for investors is that it is the boring stuff that works. And nobody wants to play a dull game”.

Social proof is another reason we are drawn to low probability. The idea of herd mentality is well-studied. If a group of our peers do something, then we feel less reservation about doing it too. This creates an environment whereby outcomes are thought of less in terms of “how likely is this” and more in terms of “wow, this is what I can win”. Consider the lottery. The greatest visibility is given to those who overcome the odds and win. You don’t hear anyone say “remember that guy who almost won the lottery?”. If you make it to the Olympics and come 10th in your chosen sport, then you are in the top 10 of that sport in the world. An incredible achievement. Yet, outside of a niche circle of influence, nobody remembers you. To point to a more recent example, recall how aggressively the rise of NFTs entered the social sphere and how quickly and silently it left.

So long as there is evidence of people overcoming the odds, the idea that you can be the next person to do so will persist. The social proof of almost everything has grown exponentially since the birth of global media and social platforms. It’s why young adults are so desperate to live beyond their means. It’s why everyone thinks they can pick a few stocks and beat the market by reading a few books and 10-Ks. In bull markets, the inception phase of buying a stock is considered in terms of “how much money I will make” and less in terms of “what are odds this stock performs well over a given period”.

Ironically, it is usually when the bull market ends, things are less ‘fun’ and fewer people are harping about their YTD returns, that investors go through their most transformative reflection periods. Because you are no longer infatuated and occupied with the pleasure of feeling like a genius, you find yourself contemplating more often. “Where did I go wrong? How can I improve?”. This is true for all vocations in life. All experience is good experience, and hard times create stronger individuals.

Despite sometimes knowing the risks, humans are drawn to high-risk, low-reward activities due to emotional drivers, cognitive dissonance, and the illusion of control. Whether it’s investing, not wearing a seatbelt, or playing a rigged game, the lure of small rewards or perceived mastery keeps us engaged, even when logic suggests we should walk away.

Maintaining a state of mind that is resistant to being pulled towards hyperbole or despair is easier said than done. Thinking of games in terms of risk and probability is a rational person’s endevour, which is a challenge in and of itself. A challenge worthy of pursuit, if you ask me.

Thanks for reading,

Conor

Data from the US Bureau of Transportation Statistics.

Nuclear energy stagnation is an example of humans focusing on high risk but not on low probability.

Nice work. I would add the more biological level reasoning:

It seems that the dopamine rush an animal gets from an unexpected reward is so much higher than when it gets an expected reward. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4767554/

For example, if you rarely give in to your dog begging at the table for some food, you will actually encourage the begging habit (that you usually want to discourage) as the dopamine is so much more intense.

Unexpected, i.e. unlikely, payouts probably make the gambler addicted (and probably bad judgement, lack of impulse control maybe).