Every great chef, investor, or artist starts humbly. They don’t know an awful lot about their trade. They begin as sponges. They make mistakes. If they are smart, they will seek to avoid repeating mistakes. If they are smarter still, they will not fear looking stupid in the short term to benefit in the long term. Good students ask stupid questions.

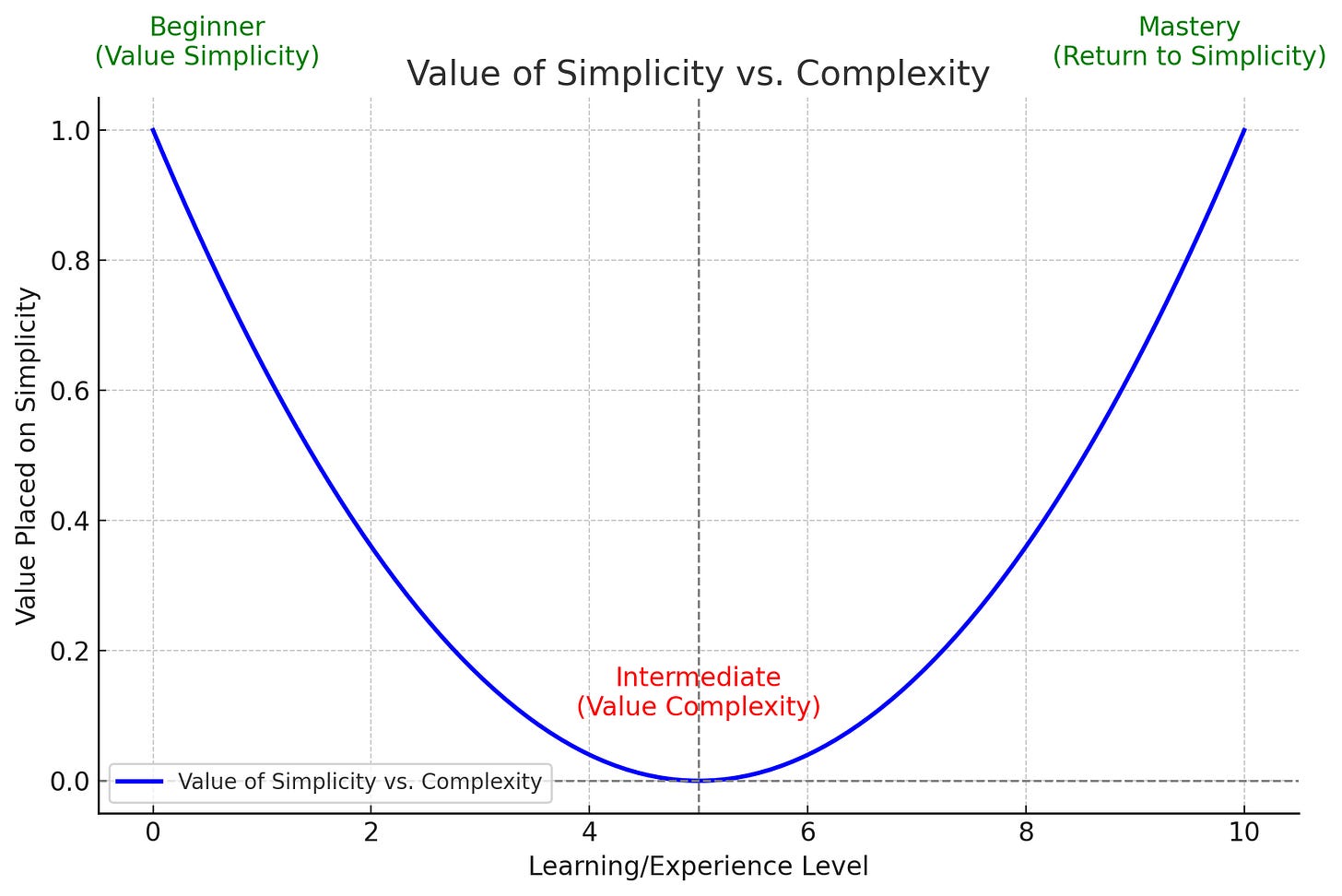

As more knowledge is accumulated, the desire the use that newfound knowledge grows stronger. In an attempt to make use of it all, tasks become burdened with complexity. The path from student to mastery begins with favouring simplicity, then complexity, and concludes with simplicity. The reason students should learn from masters, and not intermediates, is that both place a high value on simplicity.

The character arc of the chef is a great example. A beginner starts out by learning the fundamentals, following recipes, and practising basic techniques. The intermediate expands their horizons, incorporates advanced techniques, and new flavour combinations, and overcomplicates. The master understands food so deeply that they can harness a few high-quality ingredients and techniques to create something seemingly understated in appearance, but incredible in flavour. Marco Pierre White once owned a restaurant that earned the accolade of three Michelin stars. In a move that was unprecedented at the time, he would later hand them back. As he matured in age and skill, he would frequently remark that the desire to return to simple cooking was his motivation.

“Simplicity is the secret to everything”, he would often say. “The more you add, the more you're taking away”. This is part of the reason why Italian food is held in such high acclaim. It focuses on the quality, not the quantity, of ingredients.

There are many great quotes like this. One of my favourites is a line from Coco Chanel, in which she suggests “Before you leave the house, look in the mirror and take one thing off”. The point is that no matter what skill or profession, the end game always appears to circle back to simplicity.

Let’s run through a couple of other examples. We’ve covered my favourite pastime, cooking, so now let’s migrate to my own profession; that of the product manager. A product manager’s role is multi-faceted. At its core it is about two things; understanding what users want and knowing how to translate that demand into a product and communicate the vision to an engineer. These two things are the simplest descriptions of the role and what both new and tenured managers will strive for. Somewhere in between, there is a hodgepodge of advanced user flows, features nobody asked for, unnecessarily complicated UI, analysis paralysis, and product bloat. The temptation to overcomplicate has not yet succumbed to the even greater temptation to strip away unwanted complexity.

Consider the iPhone. It’s a technological wonder. It’s many human’s third arm and second brain. Yet it’s not the most technically advanced phone on the market. It hasn’t been for some time. What it does better than any other product in the market, and dare I say the world, is package up technology which is so incomprehensibly complex to the common individual in a manner that is so sophisticatedly simple.

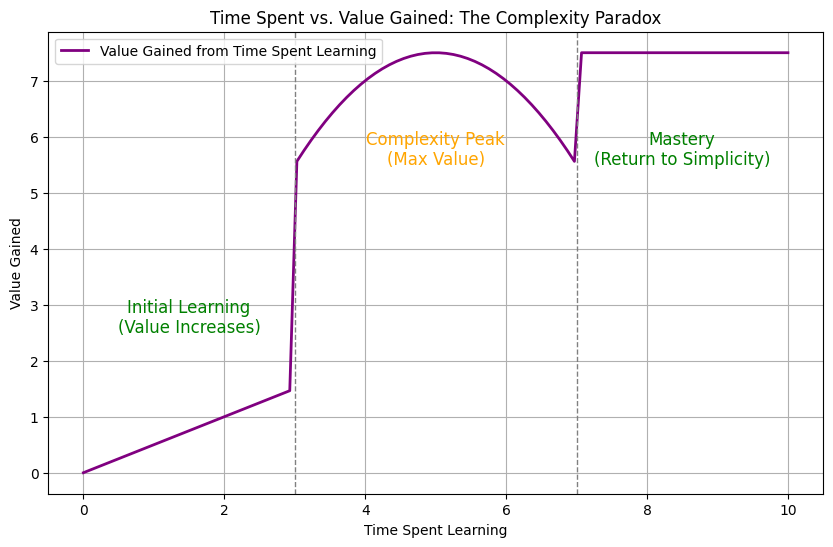

Lastly let’s consider one of my greater passions in life, investing. Every single investor follows the Good Will Hunting Arc (see below).

You start at a crossroads with a seemingly endless number of paths to explore. Fundamental analysis, technical analysis, value investing, accounting, benchmarking, long-term, short-term, derivatives, discounted cash flows, models, macro, and the list goes on. This tends to be when you are at your most humble. When you pick up a few things you likely go through various phases. Like teenagers going through a goth or chav moment, investors will find themself switching genres often as they try to find the style that suits their temperament. I am sure everyone goes through a small cap phase. Some begin to fetishize macro and illiquid deep-value opportunities. As you pick up new knowledge, you try your best to cram as much of it into your process as possible.

But a fatter checklist doesn’t equate to better returns. Another way to frame it is simply by the transition of learning that it’s incredibly difficult to beat the market, to then feeling confident you can do it over the long term, to ultimately appreciating the difficulty of such an act. I am no beginner, but I am no master either. Over time I have come to appreciate that I’d rather optimise for spending as little time in front of a screen as possible. Do the heavy work up front, keep an active watchlist of opportunities, track the handful of core KPIs that make the business tick for each company, understand the thesis, be prepared to re-allocate if it derails or you feel you were wrong, keep up to date each quarter, and let time do its thing. Stay away from CNBC, avoid placing too much emphasis on macro, and aim to check your returns as infrequently as possible. A richer news diet is more likely to congest your clarity. Like information-cholesterol for the brain.

Beginners and masters share one thing in common; a penchant for simplicity. They are two different forms of desire. The beginners want things to be communicated simply so that they can understand. The master wants that too, but the differences lie in from their ability to take a complex subject matter and communicate it as though it were simple. When you hear someone say “they make it look easy!” it’s because that person has a deep enough level of understanding in their craft to do so.

“Simplicity is the ultimate sophistication. It takes a lot of hard work to make something simple, to truly understand the underlying challenges and come up with elegant solutions. It's not just minimalism or the absence of clutter. It involves digging through the depth of complexity. To be truly simple, you have to go really deep. [You have to deeply understand the essence of a product in order to be able to get rid of the parts that are not essential”. - Steve Jobs

A student asks two mentors a question. The intermediate will respond with an answer that leaves the beginner with more questions. The master will respond in a way that answers the question.

How do I cook a perfect steak? They may ask.

Answer 1: "To cook the perfect steak, start by choosing the right cut, like a ribeye or filet mignon, with marbling. Make sure the steak is at room temperature before cooking. Season it with a mix of kosher salt, black pepper, garlic powder, and a hint of rosemary. Use a cast-iron skillet, and preheat it to exactly 260°C. Sear the steak for exactly 2 minutes on each side, then baste it with a mixture of butter, thyme, and crushed garlic. After that, transfer it to a 190°C oven and use a meat thermometer to ensure the internal temperature reaches 55°C for medium-rare. Let it rest for 5-7 minutes under a foil tent to redistribute the juices. Serve it on a warm plate with a side of homemade chimichurri sauce and garnish with sea salt flakes."

Answer 2: "Season it well, cook it hot and fast, and let it rest before eating."

As for why people tend to gravitate back to simplicity, I think there comes a point when the value gained from time spent learning a particular subject matter begins to diminish.

At the start the rate of growth is incredible. Everything is new. By the time that begins to peak the newness dissipates, complexity fades, and a desire for elegance comes to the fore. The new challenge is taking what you know, and making it seem simple. That is the paradox of the complexity curve.

Thanks for reading,

Conor

Loved today’s article Conor! It’s been a while since we’ve connected on the cooking front. Hope all is well

Buenos días desde España! Magnífico artículo. Muy bien explicado y con ejemplos muy claros. Gracias por todo lo que aportas! Un saludo!!!