Only Pessimists Pick Bottoms

Two essays that perfectly capture the difference between long and short term thinking

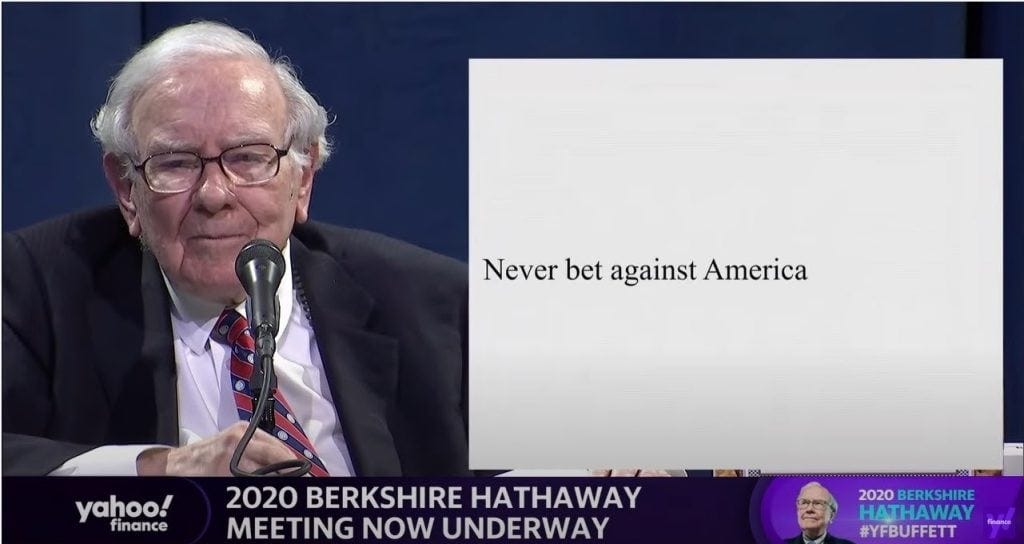

It was a Saturday, May 2nd 2020, that Warren Buffett sat down during Berkshire’s 2020 annual shareholder meeting and advised the world to “never bet against America”. Months earlier, a decade-long bull run had concluded at the hands of a global pandemic. Like the virus, fear had spread throughout markets in a contagious fashion. The S&P 500 had tumbled 34%, governments were sending checks in the mail, and consumers were locked indoors. Lots of things happened in 2020; Brexit was officially concluded, Kobe Bryant tragically passed, Australian wildfires ravaged Down Under, the rise of the Tiger King, and Harvey Weinstein was convicted. But the year 2020 will forever be remembered as the year the pandemic began.

By the time Buffett sat down to address his shareholders, the market had recovered somewhat; up ~25% from what would become the bear market low set in March. Still down ~17% from the pre-pandemic high, the world was in a state of panic. While historians may look at this period in markets as a relative “flash in the pan” (where the fastest retracement of a bear market would take place shortly after, retaking the high by August) it was anything but. Nobody was certain of what would happen next, and I am confident few believed the market would go on to put up a +18% year in 2020. Nevertheless, the message from Buffett was clear. Despite what might be going on in the world, never bet against America.

His speech resembled one he gave during the last major spate of global panic in markets; the 2008 financial crisis. Then, he pined an op-ed in the New York Times titled “Buy America. I Am.”. Today I want to share two short essays with you. One is the aforementioned op-ed from the New York Times, shared five months before the market bottom. It was bold, optimistic, intellectually honest, and emphasized riding out the short term to stay focussed on the long term. The other, an op-ed in the Los Angeles Times on the same week the market bottomed, paints a startling contrast of pessimism. The author laments long-term investors and cries that “This is the time for hysteria”. Unbeknownst to him, this was the time for maximum optimism.

The two essays perfectly capture the difference between long and short-term thinking. As one author looks forward and buys, the other looks around him and cries. If anything, these essays and their proximity to one another and the market bottom, ought to give you a chuckle, or food for thought.

Buy American. I Am.

Warren E. Buffett

Oct. 16, 2008

The financial world is a mess, both in the United States and abroad. Its problems, moreover, have been leaking into the general economy, and the leaks are now turning into a gusher. In the near term, unemployment will rise, business activity will falter and headlines will continue to be scary. So ... I’ve been buying American stocks. This is my personal account I’m talking about, in which I previously owned nothing but United States government bonds. (This description leaves aside my Berkshire Hathaway holdings, which are all committed to philanthropy). If prices keep looking attractive, my non-Berkshire net worth will soon be 100 percent in United States equities.

Why?

A simple rule dictates my buying: Be fearful when others are greedy, and be greedy when others are fearful. And most certainly, fear is now widespread, gripping even seasoned investors. To be sure, investors are right to be wary of highly leveraged entities or businesses in weak competitive positions. But fears regarding the long-term prosperity of the nation’s many sound companies make no sense. These businesses will indeed suffer earnings hiccups, as they always have. But most major companies will be setting new profit records 5, 10 and 20 years from now. Let me be clear on one point: I can’t predict the short-term movements of the stock market. I haven’t the faintest idea as to whether stocks will be higher or lower a month or a year from now. What is likely, however, is that the market will move higher, perhaps substantially so, well before either sentiment or the economy turns up. So if you wait for the robins, spring will be over.

A little history here: During the Depression, the Dow hit its low, 41, on July 8, 1932. Economic conditions, though, kept deteriorating until Franklin D. Roosevelt took office in March 1933. By that time, the market had already advanced 30 percent. Or think back to the early days of World War II, when things were going badly for the United States in Europe and the Pacific. The market hit bottom in April 1942, well before Allied fortunes turned. Again, in the early 1980s, the time to buy stocks was when inflation raged and the economy was in the tank. In short, bad news is an investor’s best friend. It lets you buy a slice of America’s future at a marked-down price.

Over the long term, the stock market news will be good. In the 20th century, the United States endured two world wars and other traumatic and expensive military conflicts; the Depression; a dozen or so recessions and financial panics; oil shocks; a flu epidemic; and the resignation of a disgraced president. Yet the Dow rose from 66 to 11,497. You might think it would have been impossible for an investor to lose money during a century marked by such an extraordinary gain. But some investors did. The hapless ones bought stocks only when they felt comfort in doing so and then proceeded to sell when the headlines made them queasy.

Today people who hold cash equivalents feel comfortable. They shouldn’t. They have opted for a terrible long-term asset, one that pays virtually nothing and is certain to depreciate in value. Indeed, the policies that government will follow in its efforts to alleviate the current crisis will probably prove inflationary and therefore accelerate declines in the real value of cash accounts. Equities will almost certainly outperform cash over the next decade, probably by a substantial degree. Those investors who cling now to cash are betting they can efficiently time their move away from it later. In waiting for the comfort of good news, they are ignoring Wayne Gretzky’s advice: “I skate to where the puck is going to be, not to where it has been.”

I don’t like to opine on the stock market, and again I emphasize that I have no idea what the market will do in the short term. Nevertheless, I’ll follow the lead of a restaurant that opened in an empty bank building and then advertised: “Put your mouth where your money was.” Today my money and my mouth both say equities.

Warren E. Buffett is the chief executive of Berkshire Hathaway, a diversified holding company.

Panicked by the stock market

Joe Queenan

Mar. 06 2009

On Monday, the Dow Jones industrial average nose-dived another 300 points. So, what advice did the perky money manager quoted in my local newspaper the next morning have to offer? “I think we’re going to look back and see that this was the best buying opportunity we’ve seen in years,” the man said. “When General Electric is selling for less than the cost of a light bulb, that’s an opportunity.” The best buying opportunity in years is now 14 months old. Financial advisors started touting it about the time the Dow hit 11,000, and they have grown increasingly enthusiastic as it has worked its way down past the 7,000 level.

As the Dow has tumbled deeper into the abyss, money managers, stock analysts and even well-meaning journalists have consistently warned laymen about the risks of throwing in the towel. Over and over, investors have been told not to panic because no one has really lost any money until they’ve sold their stocks. Meanwhile, the market has surrendered more than half its value and seems perfectly prepared to continue its merry toboggan ride south. So even if you haven’t actually lost any money yet, it may seem as if you’ve lost money. It may seem, in fact, as if you’ve lost half your life’s savings.

About a year ago, I began collecting hilarious articles warning the public not to make the mistake of panicking. My favourite is “The Economy is Fine (Really),” which ran in the Wall Street Journal on Jan. 28, 2008. In it, Brian Wesbury, chief economist for First Trust Portfolios, opined: “It is hard to imagine any time in history when such rampant pessimism about the economy has existed with so little evidence of serious trouble.” Wesbury also noted that “initial unemployment claims, a very consistent canary in the coal mine for recessions, are nowhere near a level of concern.” He concluded: “Dow 15,000 looks more likely than Dow 10,000. Keep the faith and stay invested. It’s a wonderful buying opportunity.”

“Are you ready for Dow 20,000?” was the headline of a March 24, 2008, Barron’s article, in which the very fine journalist Jonathan Laing allowed “veteran strategist” James Finucane to hang himself. Finucane believed that “months of stock liquidation and cash buildup, horrible sentiment and a bailout that could alter investor psychology have lit the fuse for an explosive rally.”

In the last year or so, there have been hundreds, if not thousands, of articles warning investors about the idiocy of panic selling. One ceaselessly regurgitated bromide warns investors that if they missed out on just a handful of the top-performing days during the 1982-2007 bull market, they would have ended up with a 25% smaller return. No one, not even Warren Buffett, can time the market, laymen are warned, and those who duck in and out do so at their peril. So stay the course. Buckle up for a bumpy ride. And whatever you do, don’t panic.

A few months ago, I decided that the time had come to panic, so I started to move a portion of my emaciated 401(k) into cash. I felt like a jerk at the time, knowing only too well that the man who is bearish on the United States of America will end up a pauper, and that if I got out now, I risked missing out on that massive, once-in-a-lifetime rally. But I was willing to take that chance, as half a loaf is better than none, and my 401(k) is now about half the loaf it once was. That first time I panicked, the Dow was trading at 9,500.

A few weeks ago, I panicked again and moved another hefty chunk out of the market. The Dow was then trading at 7,500; now it is approaching 6,500. I fully expect to panic again at 6,000, probably at 5,000, and might even get in a bit of late-in-the-day panicking at 4,000. Tentatively, I am drawing a line in the sand at the crucial watershed of Dow 3,000, because any hysterical selling beyond that point would be anti-American and counterproductive. But even that hideous benchmark is subject to revision. I realize that I have come late to the panic mode, but as my father always said: No matter how bad you have been burned, it is never too late to try dousing yourself with water. Remember that, son.

One thing that encourages me to panic is the steady cascade of admonitions from luminaries urging me not to panic. Last week, professional cheerleader and Wharton School professor Jeremy J. Siegel wrote an Op-Ed article in the Wall Street Journal arguing that stocks are significantly undervalued because the S&P calculates its earnings incorrectly. I couldn’t understand all of his reasoning, but basically, he said that stocks were cheap. The next day, Jason Zweig, author of the Journal’s “The Intelligent Investor” column, fired back: “The belief that stocks become virtually riskless if you just hold them long enough -- popularized a decade ago in books like Jeremy Siegel’s ‘Stocks for the Long Run’ and James Glassman and Kevin Hassett’s ‘Dow 36,000’ -- has been shattered by reality.” Hassett, by the way, was one of John McCain’s top advisors. Talk about dodging a bullet.

The lower the Dow goes, the more adamantly some professionals insist that the worst is over. In this week’s Barron’s, portfolio manager William D’Alonzo said: “Whether it takes six months or several years for this crisis to bottom, we believe the market has largely discounted the economic downturns, and that it is essential to remain in the market to take part in its eventual recovery.” No thanks; I’m panicking.

Meanwhile, Tobias M. Levkovich, chief U.S. equity strategist for Citigroup Global Markets, wrote in his Feb. 26 report: “Stock prices are showing up as attractive against other assets.” Since then, the Dow has dropped almost 700 points more. Citigroup, it bears noting, is a banking colossus that may cease to exist as an independent entity soon, if rumours of impending nationalization are true. In other words, the top analyst for a bank that has effectively imploded is telling investors to buy stock in the equity market that Citigroup helped to destroy. This is a little bit like the chief petty officer on the Titanic offering up survival tips: Whatever you do, don’t abandon ship; it’s cold out there in the North Atlantic.

Well, with all due respect, sir, I know that your intentions are honourable and that you’ve got loads of experience in this field. But right now, I’m no longer accepting advice from employees of the White Star Line. There is a time for hysteria and a time when cooler heads should prevail.

This is the time for hysteria.

Joe Queenan writes frequently for Barron’s, the New York Times Book Review and the Guardian.

To conclude, here is a chart showing the publish date of both articles.

Thanks for reading,

Conor

Great Article! I think of put into perspective those downward trends are a relatively short term phenomenon. A true value focused investor really shouldn’t bother to exactly pick any bottoms

Got Goosebumps re-reading Warren’s Op Ed-Hall of Fame Thinker, Writer, Philanthropist, beyond Investor & Businessman. Great piece & so funny the spectrum of human reaction to such adversity! Remember staying the course but being tearful and beside myself as my father also told me to keep the faith in capitalism and be patient as I turned gray that year!