In Defence of Capitalism

"The ****ing supermarkets are making record breaking profits"

It was the morning of 20th October. My dream, rudely cut short by the bellowing of my morning alarm. I shot up out of bed, stumbled to the other side of the room and restored silence. My phone screen read 6:30 am, emitting the only source of faint light in an otherwise dark room. The cold clung to my bones, as it does in the Autumnal mornings of Scotland. With haste, I dress myself in trousers, a t-shirt, and a sweater. That should put the chill at bay. In a contradictory fashion, I head to the bathroom and repeatedly splash my face with cold water.

With the blood vessels in my face constricted and my nerve endings now forcefully awakened, I grab a portable lamp, my book, and a laptop and migrate to the kitchen. The first hour or so of my day is usually spent reading and drinking coffee. Some time passes.

As the last chapter of my reading time concludes, and the sun begins to illuminate the city through my kitchen window, I perch myself on the counter. Opening my MacBook, I discover that vast swathes of the internet are down. The culprit? Amazon Web Services. It’s the type of incident we’ve all experienced before. Within a day or two, it will all be over.

Later that morning, I was relieved to stumble across firm evidence that the world was steaming ahead as usual. While cloud service outages come and go, you can always count on politicians who lack a basic understanding of something to try and dictate how those things should work.

This time, it was the turn of US Senator Elizabeth Warren. “If a company can break the entire internet, they are too big. Period”, she proclaimed. Promptly followed up by her catchphrase, “It’s time to break up Big Tech”.

I won’t be wasting my breath explaining why this is a delusional take this morning. Rest assured, Elizabeth will reappear later in this text.

Statements like these are big, bold, and attention-grabbing. They make great headlines because they exert a magnetic attraction, sucking both sides of the peanut gallery into the centre with a calamitous BANG like protons in a Hadron Collider. The protons, in this case, are the vocal proponents and opponents to the proposed solution.

This comment from Senator Warren reminded me of something which occurred days earlier.

Browsing through the internet, I noticed an old high school friend shared a video of someone complaining about the cost-of-living crisis in the United Kingdom (UK). My curiosity got the better of me, and I watched it. The man who goes by the pseudonym “Tattooed Dave” complains that the energy companies are earning ‘record breaking profits’ in the wake of rising energy prices. Most ludicrously, he proceeds to single out Tesco, the largest supermarket in the UK by market share and sales.

“The ****ing supermarkets are making record breaking profits. Tesco could pay every one of their employees a £10,000 a year bonus. They would still make a profit”.

A few unfounded soundbites presented as “facts” and a couple of swear words later, the video ends. My brain cells begin the slow process of regeneration.

The video implies that Tesco is taking advantage of the UK consumer and is directly benefiting from the fragile and inflationary environment post-pandemic. We’ll get to why that isn’t true in a second, but this isn’t a phenomenon unique to the UK.

US Senator Elizabeth Warren (told you) has been vocal in her belief that US supermarkets are to blame. In a 2024 hearing, her opening statement claimed that “Grocery prices are up because of good old-fashioned corporate price gouging”. It’s true that, pretty much globally, grocery prices exploded during the pandemic, and in most cases, they’ve continued going up even though the pandemic is now behind us. Warren has a track record for spinning encapsulating headlines that lack nuance. It’s what sells newspapers and attracts the confirmation-bias-seeking crowd. The same goes for the other side, too, don’t get me wrong.

Seeing people I know, many of whom are smart and capable, share nonsensical information like this makes me contemplative. Why do so many people my age, young people, have such anti-private-sector views? Why do they so easily succumb to this narrative that capitalism is “bad”? There are cultural, educational, and structural reasons, all feeding off each other.

I don’t know the answer.

Perhaps it’s because the private sector is an easy scapegoat for politicians and the media to blame for the economy’s problems. Ironically, the sitting government appears to do everything in their power to squash the motivations and prosperity of private enterprises.

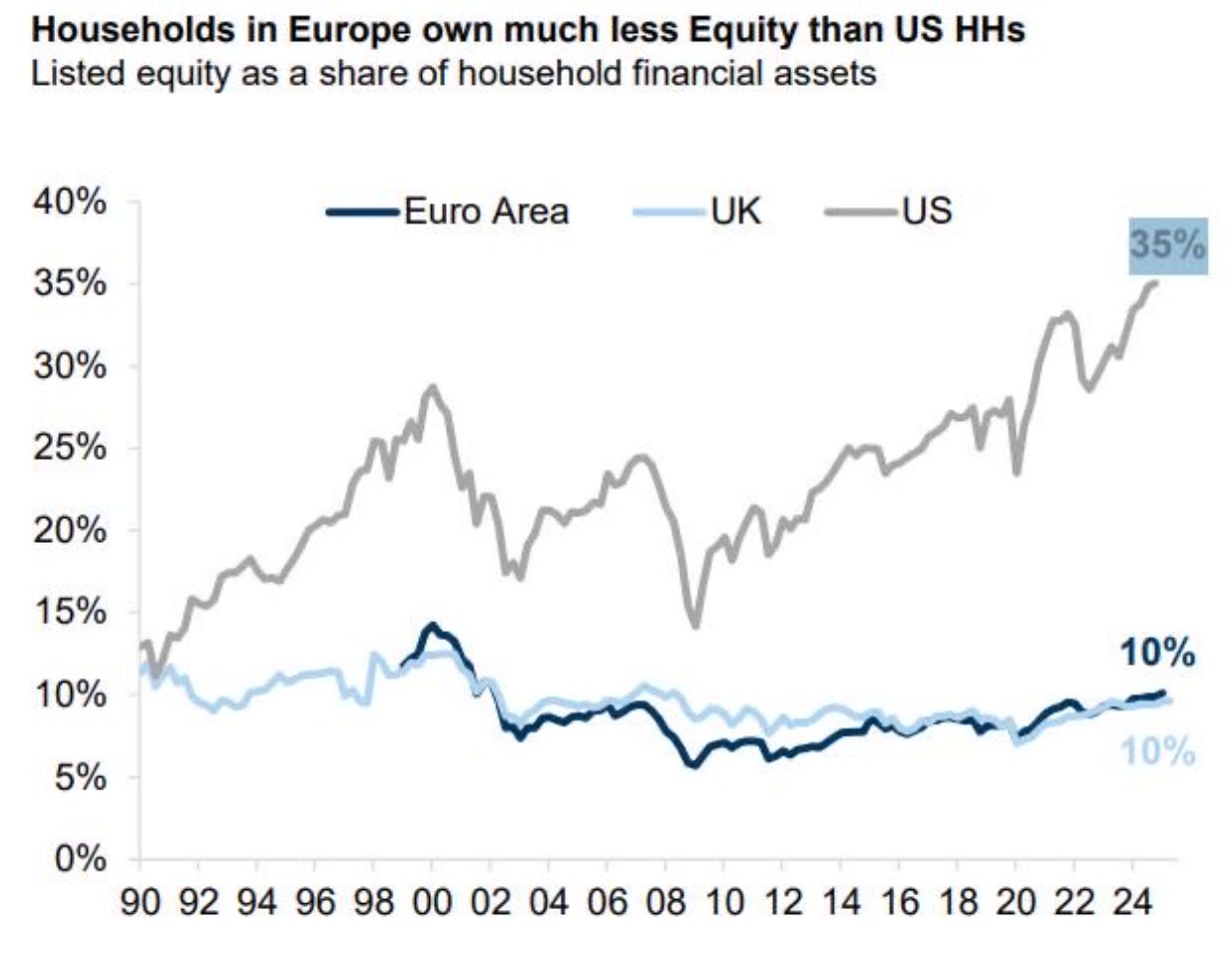

Part of it is education, or rather, the lack of it. It is estimated that as few as ~25% of UK adults actively invest in the stock market as of 2024, compared to more than 50% in the United States. It’s no secret that the citizens of the UK are relatively risk-averse compared to their American cousins. When you don’t own equities, you don’t see capitalism as your system. You see it as someone else’s.

With respect to household wealth, the US stands head and shoulders above the UK and EU, with ~35% of household financial assets devoted to listed equities, compared to 10% for the UK and Euro Area.

The culture around risk and aspiration in the UK is complicated. Ambition often feels like a character flaw. It can be likened to the famous ‘crabs in the bucket’ maxim, where anyone climbing becomes a target for being pulled back down. Pair that with low wages, swathes of red tape, and you have a culture that sneers at success instead of celebrating it.

One need only skim the headlines of the Financial Times to see the symptoms. Countless UK-listed companies are being snapped up on the cheap by American private equity, others shifting listings to New York, and CEOs quietly relocating for tax sanity. The message is clear: ambition enjoys a warmer climate elsewhere.

I’ve been reading Andrew Sorkin’s ‘1929: The Insider Story of the Greatest Crash in Wall Street History’. It recounts one of Winston Churchill’s visits to the States in 1929, where he noted that, unlike in Europe, “the social life of the United States is built around business”. It’s a sentiment that feels as true today as it did nearly a century ago. The UK still can’t decide whether it admires that or despises it. Some things never change.

I digress.

A lot of ordinary citizens find arguments like “Tesco are the bad guy” encapsulating. We can pontificate on exactly why. If you lack a basic understanding of finance, it becomes significantly easier to believe this at face value because the ability to exercise critical thinking towards the matter is absent. This is true for every complex subject matter.

Take the health and fitness industry as one example. The majority of the public is not versed in the disciplines that would provide a more critical lens through which to discern claims. They are not nutritionists, dieticians, biologists, and so on. They are prone to believing claims at face value. In the 70s and 80s, the in-vogue war cry of the health industry was that “fat is bad”. As the consensus shifted towards the reality that, in fact, not all “Fat” is bad, the stigma of the word “fat” still lingers decades later. Various other food groups have transformed from villains to superheroes over time. Eggs and their “link” to cholesterol being one.

It sounds unfair that these huge companies earn billions in profits while the average household is blighted by ever-increasing grocery costs.

Big Media know this, and capitalise on it. Despite knowing that absolute values tell a one-sided story, they push this narrative onto the public, which, now more than ever, lacks the desire to interpret headlines via critical thinking. In practice, this means they read the headline, consume the Short-form video or the soundbite, and they assess whether this confirms their prior beliefs. If it does, it becomes a new fact in their arsenal. If it doesn’t, they simply ignore it.

Rarely will someone explore the merits of the claim.

The ****ing supermarkets are making record breaking profits

Let’s now address Tattooed Dave’s claims that “The ****ing supermarkets are making record breaking profits”. I’ve seen this exact headline blasted across various news outlets before, so we can be assured that Dave picked up this argument from the media cycle and has decided to run with it. Due to a dwindling number of publicly traded large supermarkets in the UK, and the fact that he singled them out, we can focus on Tesco.

Spoiler… the headline is false.

Tesco are enjoying record sales. The £69.9 billion the company generated in fiscal year 2025 represents an all-time high and a 2.5% increase on the prior year. Compared to the period ending February 2020 (Tesco’s fiscal 2020), the company’s sales have grown 8% after recovering from an 11% decline in the first year of the pandemic (Tesco’s fiscal 2021).

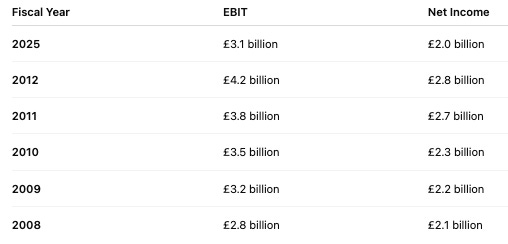

If we run our finger down the income statement and focus on operating income (EBIT), Tesco reported £3.1 billion in EBIT in the latest fiscal year (2025) with £2 billion in net income after interest and tax. This does reflect the highest earnings over the course of the current decade. But a glance at Tesco in the pre-scandal era of 2009 through 2012 (fiscal years) shows that this is by no means “record breaking profits”.

Tesco’s operating income and net income were higher than 2025 in 2009, 2010, 2011, and 2012, with the latter year representing the high-water mark that has remained unchallenged.

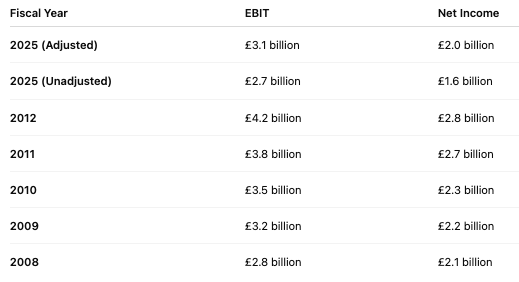

But here’s the catch. I tricked you (sorry). The numbers in the above table for fiscal year 2025 flatter Tesco, as they are adjusted to exclude certain non-recurring items such as restructuring, property write-downs, and expenses linked to the sale of Tesco Bank. The unadjusted numbers for the latest year are moderately worse. In the latest fiscal year, Tesco’s unadjusted EBIT was £2.7 billion with £1.6 billion in net income.

This puts to bed the first claim from Dave’s video. Tesco are not earning record breaking profits. But what about the second claim?

“Tesco could pay every one of their employees a £10,000 a year bonus. They would still make a profit”.

As per Tesco’s latest annual report, the company employed an average of 341,108 people in the fiscal year 2025. If Tesco paid 341,108 employees a bonus of £10,000, their balance sheet would be £3.4 billion lighter. In the real world, this payment would be an operating cost. Tesco’s £2.7 billion in operating income would not cover the cost, so the company would swing to an operating loss of £700 million before considering interest and tax.

Now they could use some of the £2.3 billion in cash they have sitting on the balance sheet, or the additional £2.2 billion in short-term liquid investments, but we’ll get into why that argument can be poo-poo’d shortly.

This firmly puts to bed the second claim from Dave’s video.

Reality called, it asked why you’ve not been around lately

There are certainly industries that are guilty of giving the consumer an unfair ride. My two cents are that the beauty of capitalism is that you don’t have to consume. If enough consumers vote this way with their wallets, or some new entrepreneur with a light bulb above their head decides to disrupt the market, the process of creative destruction should nudge the market’s invisible hand to do the bidding of the people. In hyper-regulated or statutory-monopoly industries, it’s not quite the same, but that’s not a facet of the supermarket industry.

We can delve into the semantics, examine industries that genuinely are malicious in their practices, but my point is this. Supermarkets are not the problem. They provide a vital service to the economy, utilising their economies of scale to offer produce and other inventory, sourced from across the world, at palatable prices. They employ hundreds of thousands of people in this country and others.

“But Waitrose and Marks & Spencer’s are so expensive”.

Don’t shop there then, go to Tesco. Go to Sainsbury’s, Asda, Lidl, Aldi, or one of the other great companies offering this service. Go to Amazon, shop online. I am not unsympathetic to the genuine struggle that inflation causes, but supermarkets, in particular, are as much a victim of inflation as the consumer. After expenses and taxes, a typical supermarket will earn ~5% operating margins. The net income margins will often be razor-thin, in the 1% to 3% range.

These margins continue to be low, despite passing on inflation to consumers during the post-pandemic inflation period. The practice of increasing prices to offset inflation has long been a common occurrence across most industries. It just happens to feel more painful when inflation is high.

Imagine for a moment that Tesco avoided increased prices to offset inflation since 2019. Their costs would still go up, as suppliers and other intermediaries passed their inflationary costs onto Tesco. The wage bill would continue to increase over time; avoiding doing so would have legal implications. Transportation, fuel, energy, packaging, all of these costs would creep higher still.

Tesco would eat the cost, and the net result would be operating losses. In plain English, Tesco would change from being a company that earns ~£0.05 for every £1 in sales, to one that loses money for every £1 in sales. That isn’t sustainable.

How does one plug the gap in the short term?

As we discussed earlier, when alluding to the imaginary £10k bonuses, Tesco could start to burn down some of the cash on their balance sheet and liquidate their short-term investments. This would naturally come at the expense of liquidity for other areas of their operations and stifle reinvestment into the business. Over time, Tesco would start to crumble as it struggles to exercise sufficient maintenance CapEx. In other words, it wouldn’t be able to afford to even ‘stand still’ as the rest of the market slowly moves forward.

What other options would they have?

The company could raise debt. Great, new cash flow. Now, how do they end up paying the interest and the principal on that debt if the company is deteriorating? Not a long-term solution. History is littered with examples of companies committing leverage-induced seppuku.

Okay Tesco. Think. What else?

They could take drastic action. Cut the dividend, shore up that cash outflow. Stop all reinvestment outflows. Start selling off assets, stores, and cutting the labour force. Conservation by consolidation. The irony of doing this, however, is that it erodes Tesco’s cost leadership advantage. As the company shrinks, the leverage they have over suppliers to source and purchase inventory at bulk discounts wanes. Their costs climb some more. Tesco ceases to be a big fish, and their ability to offer lower prices to consumers will all but vanish.

It’s a self-perpetuating doom cycle. Generally speaking, if a market/sector has high rates of competition, which I believe the UK supermarket does, this is good for consumers and tougher for businesses. If Tesco disappeared tomorrow, there would be considerably less competition in the supermarket industry. Fewer reasons to try to keep prices low to compete with Tesco.

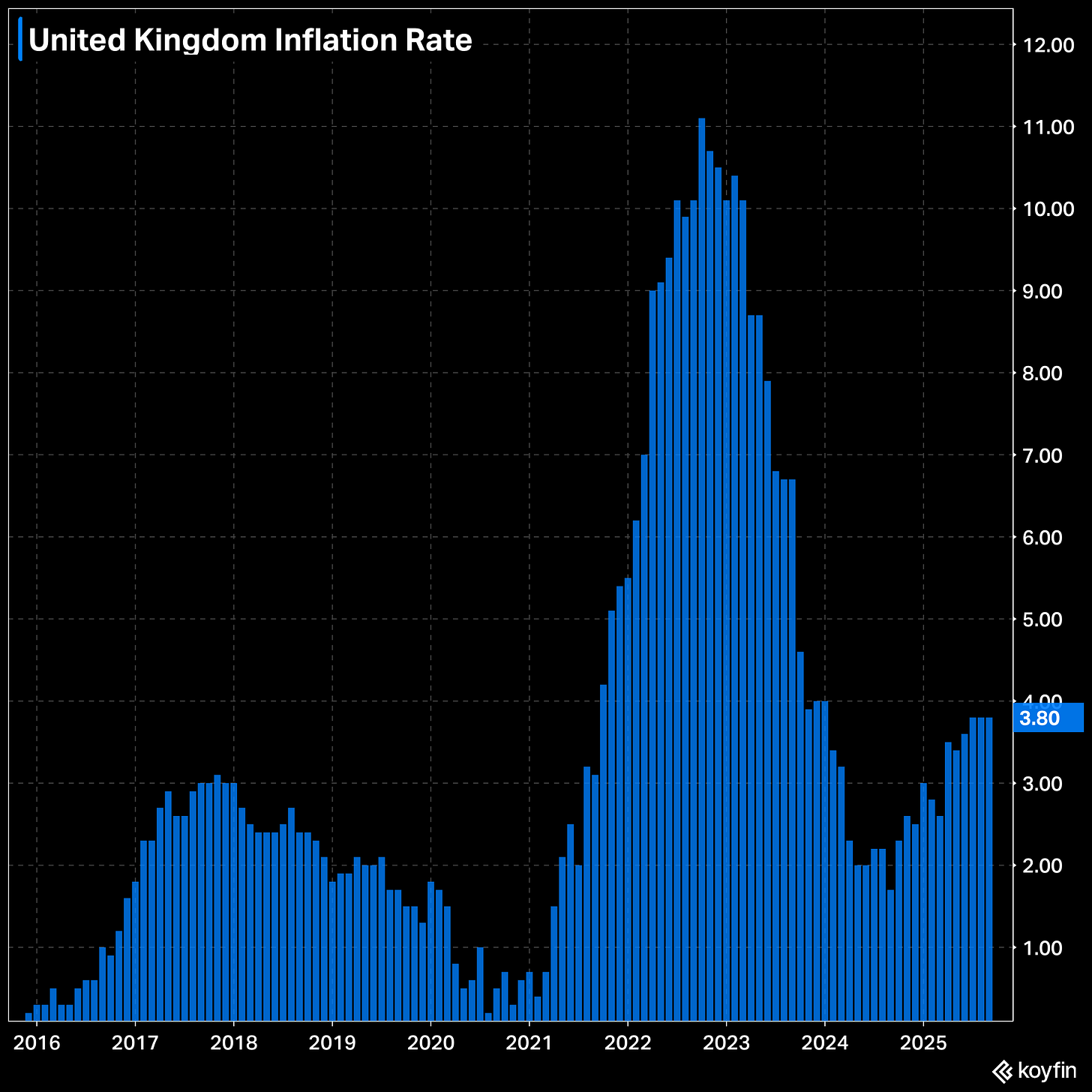

Inflation is like a viscous web that seeps into every crevice and corner of the economy. Into our homes, our companies, our state of well-being. One can make the argument that the spotlight ought to be shone on the government, who decide the policies, and the central banks, which influence the cost of capital and the money supply. Of these three branches, government, private sector, and central banks, it would be fair and reasonable to say that all suffer because of inflation.

One could say the private sector inherits inflation, much like the consumer, not its architect. And yet, as ever, it’s the easy target.

Thanks for reading,

Conor

The grocery business is so low margin, it's hard to imagine anyone would want to be involved with it.

Too bad “Tattooed Dave” and his fan base will never read your post.

We have a similar mood in Canada.

Back in 2024, people were trying to boycott one of the grocery chains...