A Hike Across History

A Brief Trip Down Memory Lane, Former Rate Hiking Cycles

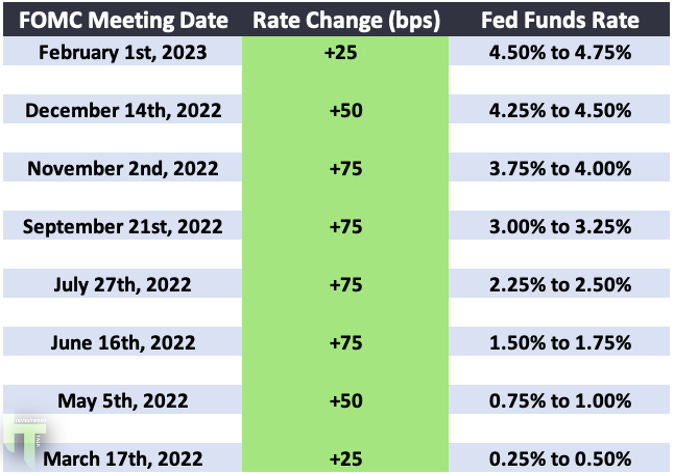

Yesterday the Federal Reserve slowed the pace of rate hikes to 25bps; their first rate decision since December 2022. This comes after four consecutive 75bps hikes between June and November, followed by one 50bps hike back in December. Fed dot plots also indicate 25bps rate hikes in both March and May, but TBD on that.

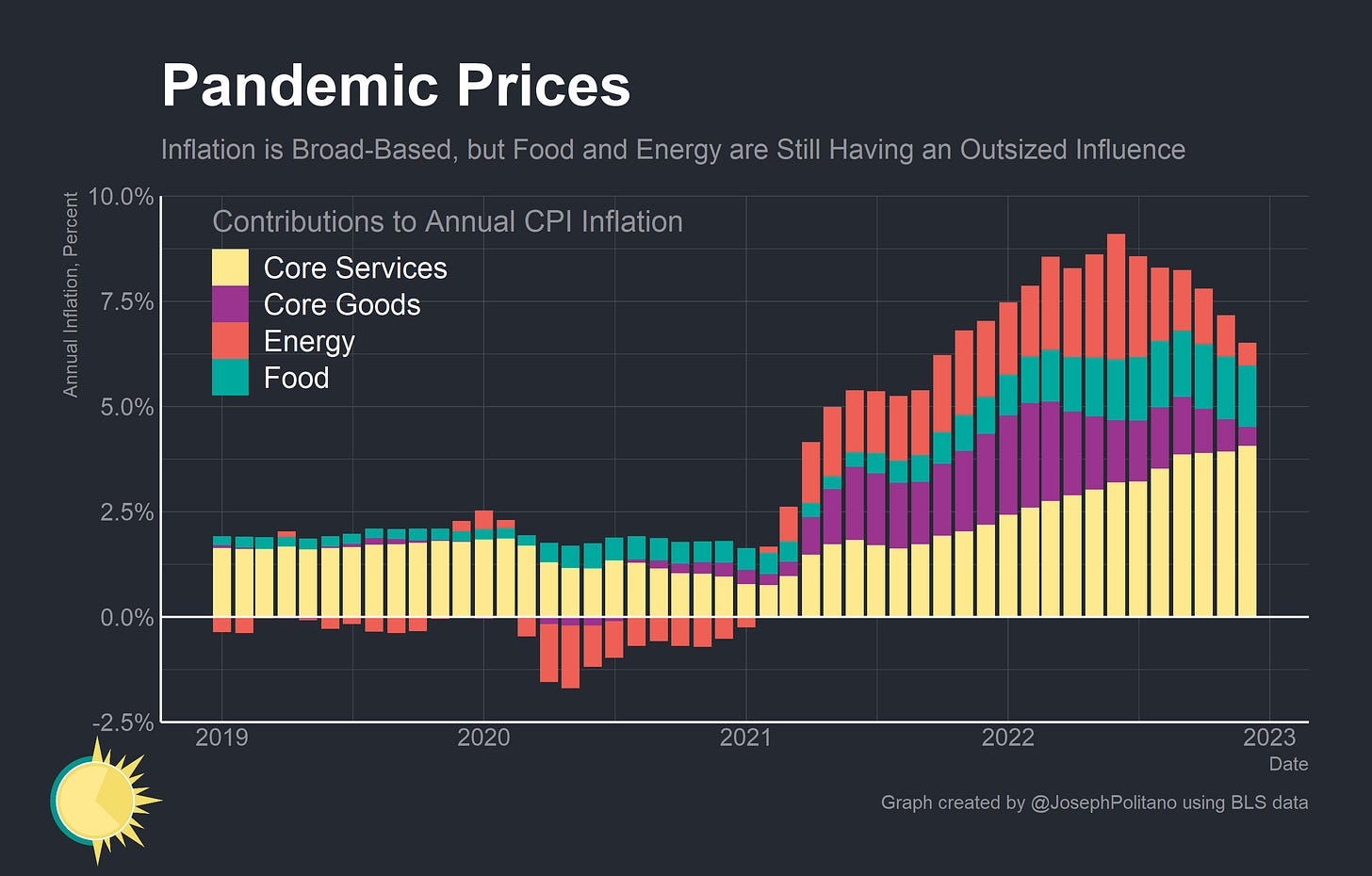

This comes as the US economy begins to show signs of normalisation and, more importantly, signs that inflation is curbing. Joseph Politano from Apricitas Economics reports:

“Inflation in the US continues to take a welcomed reprieve—driven by falling gasoline and used car prices, the Consumer Price Index (CPI) grew less than 6.5% over the year ending December, the slowest pace since October 2021. Critically, the makeup of US inflation has changed drastically over that time period—going from being mostly driven by supply-side shocks to food, energy, and core manufactured goods to being driven almost entirely by the combination of food and more demand-driven cyclical prices for core services (which includes housing).”

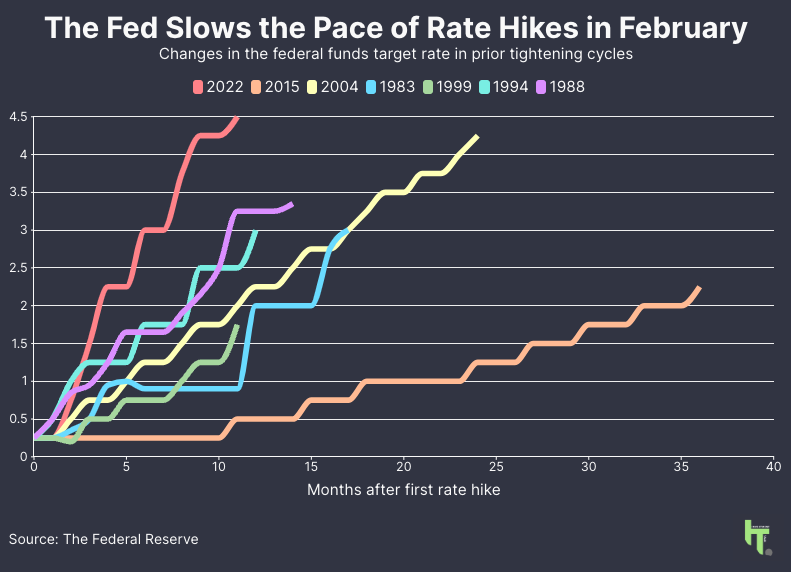

Even with the expected slowdown, the current rate hike cycle remains unprecedented; it’s the sharpest and most aggressive in modern history.

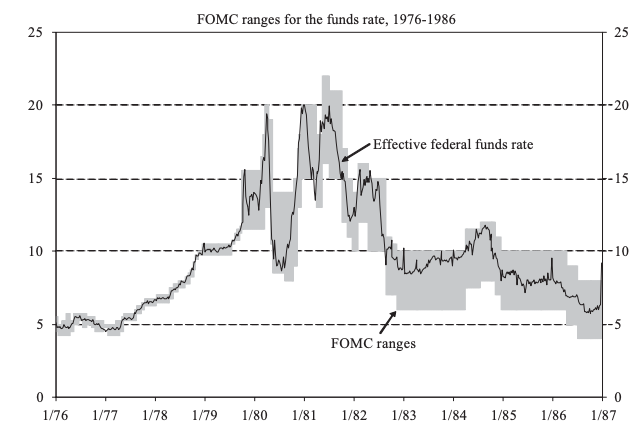

Instead of droning on about what might happen during this hiking cycle (i.e, the unknowable), I thought it might be fun to take a look back at prior rate cycles. Note, I will be brushing past a lot of details here, this isn’t meant to be an encyclopedia of market history. Despite being one the most aggressive hike cycles in recent history, the upper range of the fed funds rate sits at 4.75% today; which is dwarfed by the tough medicine that Paul Volcker forced consumers to swallow in the early 1980s. At the peak in 1981, Volcker raised rates to as high as 20% to combat inflation.

The Paul Volcker Era & The Great American Inflation

1979 to 1987

When Paul Volcker was appointed Chairman of the Federal Reserve in August 1979 the annual average rate of inflation in the United States stood at ~9%; having grown 300bps over the last year. Over the preceding two decades the Fed had employed restrictive monetary policy to combat rising inflation, but each time it came back. They had enacted small rate increases but Volcker felt more drastic action was required. In the late 1970s, the fear was that despite already being at 9%, inflation was set to continue heating up; ushering in the second vicious term of double-digit inflation in less than a decade.

By the early 1980s, it peaked at 11%. A few months after his appointment, Volcker would summon a surprise meeting in October 1979, where he would lay out his plan to dramatically tighten monetary policy to shock the economy into disinflation. That same month, rates would climb to 13.7%. Just 5 months later, they would hit 17.6%, and between the rest of 1980 and 1981, they would climb to as high as 20% on a few occasions. The goal was clear; increase rates, reduce spending, slow the economy, and get inflation under control. Volcker was aware that this would cause a lot of pain to the American people but saw the actions as necessary. He would later recall that if the Fed took a softer approach:

“The pain we have suffered would have been for nought—and we would only be putting off until some later time an even more painful day of reckoning.”

Paul Volcker, 1983

The Reserve did eventually manage to subdue inflation, but it took them two aggressive rate hiking cycles, and two recessions, to get there. Many credit Volcker for the decision to engineer two significant, but short-lived, recessions to cut consumer spending and forcibly neuter inflation.

First, a cycle which took the funds rate close to 20% in late 1979; resulting in a mild recession from January 1980 to July 1980. This was followed by a similar cycle in 1981 which would give birth to a second recession; lasting from July 1981 to November 1982.

The second recession proved to be far more severe; as unemployment peaked at 10.8% in December 1982 compared to the 7.8% during the 1980 recession. For context, this eclipses the 10% peak in unemployment during the 2008 crisis.

But it worked. By the time Volcker left office in 1987, inflation fell to 3.4%. The new steady state of low inflation remained the norm in the United for decades to come. Now the US faces its most significant bout of inflation since Volcker’s era and it is up to Jerome Powell to deal with it. Some of Powell’s commentary, such as this statement from September ‘22 (when the Fed raised rates 75bps to 3.00%) echoes that of Volcker’s. During the Jackson Hole conference, he candidly remarked that this decision would “bring some pain to households and businesses”.

“We have got to get inflation behind us. I wish there were a painless way to do that. There isn't. We have to get supply and demand back into alignment. The way we do that is by slowing the economy.”

Jerome Powell, 2022

But I’m not sure Powell is as much of an advocate for pushing the economy into a recession as Volcker was. I believe he is still trying to engineer a soft landing. I’ll leave that to you to decide.

The Gulf War Rate Cuts

1990 to 1992

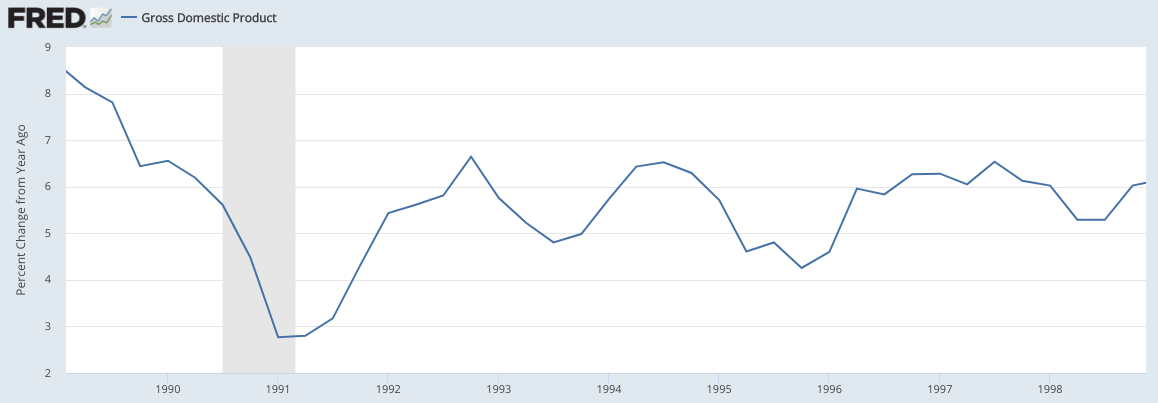

The Gulf war recession was triggered by a supply shock (i.e, war) in oil that caused the price per barrel to increase significantly. The recession itself was mild and short; lasting just eight months. The Federal Reserve began cutting rates to stimulate the economy on July 1990, the month the recession began, and would continue chipping away for more than two years.

Despite the recession ending in March 1991, some areas of the economy took longer to recover, with unemployment only peaking at 7.8% one year later in the summer of 1992.

A Succesful Soft Landing

1994 to 1995

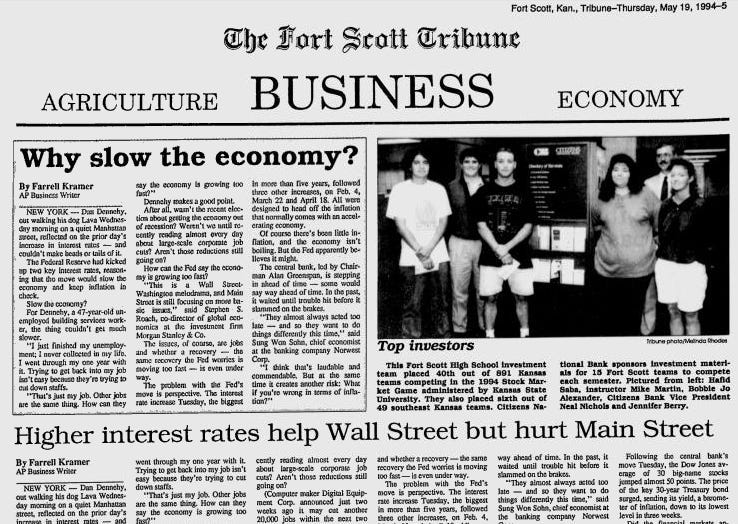

A soft landing is what economists refer to as a cooling of the markets that manages to sidestep a recession usually triggered by sharp increases in interest rates. Whilst there’s a lot of talk about a soft landing as far as the current day is concerned, back in 1994/95, Alan Greenspan actually managed to pull one off'; quite successfully.

Following the minor recession in the US at the beginning of the 90s, the economy was humming. GDP growth had begun to accelerate once more, and unemployment continued to trickle down from the highs of 1992 and reached 6.5% by the end of 1993. Over the course of the next 12 months, Greenspan almost doubled the fed funds rate; with the 75bps hike in November 1994 being the first of that magnitude in 30 years.

The aggressive action befuddled some; inflation was at its lowest and most stable point (~2.6%) in years. But with the economy now booming and inflation being so low, the stock market was ripping. Meanwhile, the 10Y treasury yield had begun to rise sharply; indicating that the bond markets anticipated inflation on the back of an overheated economy.

In order to take a proactive stance, Greenspan and his peers would enact the first of several rate hikes in February 1994; with the decision grabbing headlines across the world.

Greenspan would admit that he feared a bubble; stating that he began raising rates “very cautiously and purposefully tried to break the bubble and upset the markets in order to break the cocoon of capital gains speculation”. He would later add; “when we moved on February 4th, I think our expectation was that we would prick the bubble in equity markets”. Needless to say, it worked for a period of time. The stock market idled for most of 1994 and the bond market would plummet; triggering the “great bond massacre”.

Economists now look back at Greenspan’s decision as one that successfully cooled down the market. Inflation remained low, and it would appear that his actions might have clipped back the wings of an economy that could have gotten out of control. But hindsight is 20/20, we will never truly know.

Following the Bond Massacre

1995 to 1997

The following two years would see a short series of rate cuts between July 1995 and January 1996. One year later, the Fed would adjust slightly and increase rates by a modest 25bps.

The mid to late 1990s was a decade of wealth creation, declining unemployment, productivity growth, and soaring equity markets. This period would have an utterly catastrophic crescendo, but more on that later. By 1995, inflation had receded enough that the Federal Reserve felt comfortable stimulating the economy once again with three mild rate reductions. In 1997, inflation (still >2%) began to creep up slightly and wishing to maintain the nation’s prosperous run and perhaps because of the inflation scars of the last decade, the Fed moved to increase rates by 25bps. The rate movements during these years are thought to have been adjustments, minor tweaks. Following Greenspan’s soft landing years earlier, the equity market quickly returned to bubbly territory and extended its meteoric rise. Bond yields continue to tumble.